Sacred Texts Taoism Index Previous Next

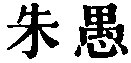

1. Among the disciples 2 of Lâo Tan there was a Käng-sang Khû, who had got a greater knowledge than the others of his doctrines, and took up his residence with it in the north at the hill of Wei-lêi. 3 His servants who were pretentious and knowing he sent away, and his concubines who were officious and kindly he kept at a distance; living (only) with those who were boorish and rude, and employing (only) the bustling and ill-mannered 4. After three years there was great prosperity 5 in Wei-lêi, and the people said to one another, 'When Mr. Käng-sang first came here, he alarmed us, and we thought him strange; our estimate of him after a short acquaintance was that he could not do us much good; but now that we have known him for years, we find him a more than ordinary benefit. Must he not be near being a sage? Why should you not

unite in blessing him as the representative of our departed (whom we worship), and raise an altar to him as we do to the spirit of the grain 1?' Käng-sang heard of it, kept his face indeed to the south 2 but was dissatisfied.

His disciples thought it strange in him, but he said to them, 'Why, my disciples, should you think this strange in me? When the airs of spring come forth, all vegetation grows; and, when the autumn arrives, all the previous fruits of the earth are matured. Do spring and autumn have these effects without any adequate cause? The processes of the Great Tâo have been in operation. I have heard that the Perfect man dwells idly in his apartment within its surrounding walls 3, and the people get wild and crazy, not knowing how they should repair to him. Now these small people of Wei-lêi in their opinionative way want to present their offerings to me, and place me among such men of ability and virtue. But am I a man to be set up as such a model? It is on this account that I am dissatisfied when I think of the words of Lâo Tan 4.'

2. His disciples said, 'Not so. In ditches eight cubits wide, or even twice as much, big fishes cannot turn their bodies about, but minnows and eels find them sufficient for them 5; on hillocks six or

seven cubits high, large beasts cannot conceal themselves, but foxes of evil omen find it a good place for them. And moreover, honour should be paid to the wise, offices given to the able, and preference shown to the good and the beneficial. From of old Yâo and Shun acted thus;--how much more may the people of Wei-lêi do so! O Master, let them have their way!'

Käng-sang replied, 'Come nearer, my little children. If a beast that could hold a carriage in its mouth leave its hill by itself, it will not escape the danger that awaits it from the net; or if a fish that could swallow a boat be left dry by the flowing away of the water, then (even) the ants are able to trouble it. Thus it is that birds and beasts seek to be as high as possible, and fishes and turtles seek to lie as deep as possible. In the same way men who wish to preserve their bodies and lives keep their persons concealed, and they do so in the deepest retirement possible. And moreover, what was there in those sovereigns to entitle them to your laudatory mention? Their sophistical reasonings (resembled) the reckless breaking down of walls and enclosures and planting the wild rub us and wormwood in their place; or making the hair thin before they combed it; or counting the grains of rice before they cooked them 1. They would do such things with careful discrimination; but what was there in them to benefit the world? If you raise the men of talent to office, you will create disorder; making the people strive with one

another for promotion; if you employ men for their wisdom, the people will rob one another (of their reputation) 1. These various things are insufficient to make the people good and honest. They are very eager for gain;--a son will kill his father, and a minister his ruler (for it). In broad daylight men will rob, and at midday break through walls. I tell you that the root of the greatest disorder was planted in the times of Yâo and Shun. The branches of it will remain for a thousand ages; and after a thousand ages men will be found eating one another 2.)

3. (On this) Nan-yung Khû 3 abruptly sat right up and said, 'What method can an old man like me adopt to become (the Perfect man) that you have described?' Käng-sang Dze said, 'Maintain your body complete; hold your life in close embrace; and do not let your thoughts keep working anxiously:--do this for three years, and you may become the man of whom I have spoken.' The other rejoined, 'Eyes are all of the same form, I do not know any difference between them:--yet the blind have no power of vision. Ears are all of the same form; I do not know any difference between them:--yet the deaf have no power of hearing. Minds are all of the same nature, I do not know any difference between them;--yet the mad cannot make the minds of other men their own. (My) personality is indeed like (yours), but things seem to separate

between us 1. I wish to find in myself what there is in you, but I am not able to do so'. You have now said to me, "Maintain your body complete; hold your life in close embrace; and do not let your thoughts keep working anxiously." With all my efforts to learn your Way, (your words) reach only my ears.' Käng-sang replied, 'I can say nothing more to you,' and then he added, 'Small flies cannot transform the bean caterpillar 2; Yüeh 3 fowls cannot hatch the eggs of geese, but Lû fowls 3 can. It is not that the nature of these fowls is different; the ability in the one case and inability in the other arise from their different capacities as large and small. My ability is small and not sufficient to transform you. Why should you not go south and see Lâo-dze?'

4. Nan-yung Khû hereupon took with him some rations, and after seven days and seven nights arrived at the abode of Lâo-dze, who said to him, 'Are you come from Khû's?' 'I am,' was the reply. 'And why, Sir, have you come with such a multitude of attendants 4?' Nan-yung was frightened, and turned his head round to look behind him. Lâo-dze said, 'Do you not understand my meaning?' The other held his head down and was ashamed, and then he lifted it up, and sighed, saying, 'I forgot at the moment what I should reply to your

question, and in consequence I have lost what I wished to ask you.' 'What do you mean?' If I have not wisdom, men say that I am stupid 1, while if I have it, it occasions distress to myself. If I have not benevolence, then (I am charged) with doing hurt to others, while if I have it, I distress myself. If I have not righteousness, I (am charged with) injuring others, while if I have it, I distress myself. How can I escape from these dilemmas? These are the three perplexities that trouble me; and I wish at the suggestion of Khû to ask you about them.' Lao-dze replied, 'A little time ago, when I saw you and looked right into your eyes 2, I understood you, and now your words confirm the judgment which I formed. You look frightened and amazed. You have lost your parents, and are trying with a pole to find them at the (bottom of) the sea. You have gone astray; you are at your wit's end. You wish to recover your proper nature, and you know not what step to take first to find it. You are to be pitied!'

5. Nan-yung Khû asked to be allowed to enter (the establishment), and have an apartment assigned to him 3. (There) he sought to realise the qualities which he loved, and put away those which he hated. For ten days he afflicted himself, and then waited again on Lâo-dze, who said to him, 'You must purify yourself thoroughly! But from your symptoms of

distress, and signs of impurity about you, I see there still seem to cling to you things that you dislike. When the fettering influences from without become numerous, and you try to seize them (you will find it a difficult task); the better plan is to bar your inner man against their entrance. And when the similar influences within get intertwined, it is a difficult task to grasp (and hold them in check); the better plan is to bar the outer door against their exit. Even a master of the Tâo and its characteristics will not be able to control these two influences together, and how much less can one who is only a student of the Tâo do so!' Nan-yung Khû said, 'A certain villager got an illness, and when his neighbours asked about it, he was able to describe the malady, though it was one from which he had not suffered before. When I ask you about the Grand Tâo, it seems to me like drinking medicine which (only serves to) increase my illness. I should like to hear from you about the regular method of guarding the life;--that will be sufficient for me.' Lao-dze replied, '(You ask me about) the regular method of guarding the life;--can you hold the One thing fast in your embrace? Can you keep from losing it? Can you know the lucky and the unlucky without having recourse to the tortoise-shell or the divining stalks? Can you rest (where you ought to rest)? Can you stop (when you have got enough)? Can you give over thinking of other men, and seek what you want in yourself (alone)? Can you flee (from the allurements of desire)? Can you maintain an entire simplicity? Can you become a little child? The child will cry all the day, without its throat becoming hoarse;--so perfect is the harmony (of

its physical constitution). It will keep its fingers closed all the day without relaxing their grasp;--such is the concentration of its powers. It will keep its eyes fixed all day, without their moving;--so is it unaffected by what is external to it. It walks it knows not whither; it rests where it is placed, it knows not why; it is calmly indifferent to things, and follows their current. This is the regular method of guarding the life 1.'

6. Nan-yung Khû said, 'And are these all the characteristics of the Perfect man?' Lao-dze replied, 'No. These are what we call the breaking up of the ice, and the dissolving of the cold. The Perfect man, along with other men, gets his food from the earth, and derives his joy from his Heaven (-conferred nature). But he does not like them allow himself to be troubled by the consideration of advantage or injury coming from men and things; he does not like them do strange things, or form plans, or enter on undertakings; he flees from the allurements of desire, and pursues his way with an entire simplicity. Such is the way by which he guards his life.' 'And is this what constitutes his perfection?' 'Not quite. I asked you whether you could become a little child. The little child moves unconscious of what it is doing, and walks unconscious of whither it is going. Its body is like the branch of a rotten tree, and its mind is like slaked lime 2. Being such, misery does not come to it, nor happiness. It has

neither misery nor happiness;--how can it suffer from the calamities incident to men 1?'

7. 2 He whose mind 3 is thus grandly fixed emits a Heavenly light. In him who emits this heavenly light men see the (True) man. When a man has cultivated himself (up to this point), thenceforth he remains constant in himself. When he is thus constant in himself, (what is merely) the human element will leave him', but Heaven will help him. Those whom their human element has left we call the people of Heaven 4. Those whom Heaven helps we call the Sons of Heaven. Those who would by learning attain to this 5 seek for what they cannot

learn. Those who would by effort attain to this, attempt what effort can never effect. Those who aim by reasoning to reach it reason where reasoning has no place. To know to stop where they cannot arrive by means of knowledge is the highest attainment. Those who cannot do this will be destroyed on the lathe of Heaven.

8. Where things are all adjusted to maintain the body; where a provision against unforeseen dangers is kept up to maintain the life of the mind; where an inward reverence is cherished to be exhibited (in all intercourse) with others;--where this is done, and yet all evils arrive, they are from Heaven, and not from the men themselves. They will not be sufficient to confound the established (virtue of the character), or be admitted into the Tower of Intelligence. That Tower has its Guardian, who acts unconsciously, and whose care will not be effective, if there be any conscious purpose in it 1. If one who has not this entire sincerity in himself make any outward demonstration, every such demonstration will be incorrect. The thing will enter into him, and not let go its hold. Then with every fresh demonstration there will be still greater failure. If he do what is not good in the light of open day, men will have the opportunity of punishing him; if he do it in darkness and secrecy, spirits 2 Will inflict the punishment. Let a man understand this--his relation both to men and spirits, and then he will do what is good in the solitude of himself.

He whose rule of life is in himself does not act for the sake of a name. He whose rule is outside himself has his will set on extensive acquisition. He who does not act for the sake of a name emits a light even in his ordinary conduct; he whose will is set on extensive acquisition is but a trafficker. Men see how he stands on tiptoe, while he thinks that he is overtopping others. Things enter (and take possession of) him who (tries to) make himself exhaustively (acquainted with them), while when one is indifferent to them, they do not find any lodgment in his person. And how can other men find such lodgment? But when one denies lodgment to men, there are none who feel attachment to him. In this condition he is cut off from other men. There is no weapon more deadly than the will 1;--even Mû-yê 2 was inferior to it. There is no robber greater than the Yin and Yang, from whom nothing can escape of all between heaven and earth. But it is not the Yin and Yang that play the robber;--it is the mind that causes them to do so.

9. The Tâo is to be found in the subdivisions (of its subject); (it is to be found) in that when complete, and when broken up. What I dislike in considering it as subdivided, is that the division leads to the multiplication of it;--and what I dislike in that multiplication is that it leads to the (thought of) effort to secure it. Therefore when (a man)

comes forth (and is born), if he did not return (to his previous non-existence), we should have (only) seen his ghost; when he comes forth and gets this (return), he dies (as we say). He is extinguished, and yet has a real existence:--this is another way of saying that in life we have) only man's ghost. By taking the material as an emblem of the immaterial do we arrive at a settlement of the case of man. He comes forth, but from no root; he reenters, but by no aperture. He has a real existence. but it has nothing to do with place; he has continuance, but it has nothing to do with beginning or end. He has a real existence, but it has nothing to do with place, such is his relation to space; he has continuance, but it has nothing to do with beginning or end, such is his relation to time; he has life; he has death; he comes forth; he enters; but we do not see his form;--all this is what is called the door of Heaven. The door of Heaven is Non-Existence. All things come from non-existence. The (first) existences could not bring themselves into existence; they must have come from non-existence. And non-existence is just the same as non-existing. Herein is the secret of the sages.

10. Among the ancients there were those whose knowledge reached the extreme point. And what was that point? There were some who thought that in the beginning there was nothing. This was the extreme point, the completest reach of their knowledge, to which nothing could be added. Again, there were those who supposed that (in the beginning) there were existences, proceeding to consider life to be a (gradual) perishing, and death a returning (to the original state). And there they stopped,

making, (however), a distinction between life and death. Once again there were those who said, 'In the beginning there was nothing; by and by there was life; and then in a little time life was succeeded by death. We hold that non-existence was the head, life the body, and death the os coccygis. But of those who acknowledge that existence and nonexistence, death and life, are all under the One Keeper, we are the friends.' Though those who maintained these three views were different, they were so as the different branches of the same ruling Family (of Khû) 1,--the Kâos and the Kings, bearing the surname of the lord whom they honoured as the author of their branch, and the Kiâs named from their appanage;--(all one, yet seeming) not to be one.

The possession of life is like the soot that collects under a boiler. When that is differently distributed, the life is spoken of as different. But to say that life is different in different lives, and better in one than in another, is an improper mode of speech. And yet there may be something here which we do not know. (As for instance), at the lâ sacrifice the paunch and the divided hoofs may be set forth on separate dishes, but they should not be considered as parts of different victims; (and again), when one is inspecting a house, he goes over it all, even the adytum for the shrines of the temple, and visits also the most private apartments; doing this, and setting a different estimate on the different parts.

Let me try and speak of this method of apportioning

one's approval:--life is the fundamental consideration in it; knowledge is the instructor. From this they multiply their approvals and disapprovals, determining what is merely nominal and what is real. They go on to conclude that to themselves must the appeal be made in everything, and to try to make others adopt them as their model; prepared even to die to make good their views on every point. In this way they consider being employed in office as a mark of wisdom, and not being so employed as a mark of stupidity, success as entitling to fame, and the want of it as disgraceful. The men of the present day who follow this differentiating method are like the cicada and the little dove 1;--there is no difference between them.

11. When one treads on the foot of another in the market-place, he apologises on the ground of the bustle. If an elder tread on his younger brother, he proceeds to comfort him; if a parent tread on a child, he says and does nothing. Hence it is said, 'The greatest politeness is to show no special respect to others; the greatest righteousness is to take no account of things; the greatest wisdom is to lay no plans; the greatest benevolence is to make no demonstration of affection; the greatest good faith is to give no pledge of sincerity.'

Repress the impulses of the will; unravel the errors of the mind; put away the entanglements to virtue; and clear away all that obstructs the free course of the Tâo. Honours and riches, distinctions and austerity, fame and profit; these six things produce the impulses of the will. Personal appearance

and deportment, the desire of beauty and subtle reasonings, excitement of the breath and cherished thoughts; these six things produce errors of the mind. Hatred and longings, joy and anger, grief and delight; these six things are the entanglements to virtue. Refusals and approachments, receiving and giving, knowledge and ability; these six things obstruct the course of the Tâo. When these four conditions, with the six causes of each, do not agitate the breast, the mind is correct. Being correct, it is still; being still, it is pellucid; being pellucid, it is free from pre-occupation; being free from pre-occupation, it is in the state of inaction, in which it accomplishes everything.

The Tâo is the object of reverence to all the virtues. Life is what gives opportunity for the display of the virtues. The nature is the substantive character of the life. The movement of the nature is called action. When action becomes hypocritical, we say that it has lost (its proper attribute).

The wise communicate with what is external to them and are always laying plans. This is what with all their wisdom they are not aware of;--they look at things askance. When the action (of the nature) is from external constraint, we have what is called virtue; when it is all one's own, we have what is called government. These two names seem to be opposite to each other, but in reality they are in mutual accord.

12. Î 1 was skilful in hitting the minutest mark, but stupid in wishing men to go on praising him without end. The sage is skilful Heavenwards, but stupid

manwards. It is only the complete man who can be both skilful Heavenwards and good manwards.

Only an insect can play the insect, only an insect show the insect nature. Even the complete man hates the attempt to exemplify the nature of Heaven. He hates the manner in which men do so, and how much more would he hate the doing so by himself before men!

When a bird came in the way of Î, he was sure to obtain it;--such was his mastery with his bow. If all the world were to be made a cage, birds would have nowhere to escape to. Thus it was that Thang caged Î Yin by making him his cook 1, and that duke Mû of Khin caged Pâi-lî Hsî by giving the skins of five rams for him 2. But if you try to cage men by anything but what they like, you will never succeed.

A man, one of whose feet has been cut off, discards ornamental (clothes);--his outward appearance will not admit of admiration. A criminal under sentence of death will ascend to any height without fear;--he has ceased to think of life or death.

When one persists in not reciprocating the gifts (of friendship), he forgets all others. Having forgotten all others, he may be considered as a Heaven-like man. Therefore when respect is shown to a man, and it awakens in him no joy, and when contempt awakens no anger, it is only one who shares in the Heaven-like harmony that can be thus. When he would display anger and yet is not angry, the anger comes out in that repression of it. When he would put forth action, and yet does not do so,

the action is in that not-acting. Desiring to be quiescent, he must pacify all his emotions; desiring to be spirit-like, he must act in conformity with his mind. When action is required of him, he wishes that it may be right; and it then is under an inevitable constraint. Those who act according to that inevitable constraint pursue the way of the sage.

74:1 See vol. xxxix. p. 153.

74:2 The term in the text commonly denotes 'servants.' It would seem here simply to mean 'disciples.'

74:3 Assigned variously. Probably the mount Yû in the 'Tribute of Yû,'-a hill in the present department of Tang-kâu, Shan-tung.

74:4 The same phraseology occurs in Bk. XI, par. 5; and also in the Shih, II, vi, i, q. v.

74:5 That is, abundant harvests. The

of the common text should, probably, be

of the common text should, probably, be

.

.

75:1 I find it difficult to tell what these people wanted to make of Khû, further than what he says himself immediately to his disciples. I cannot think that they wished to make him their ruler.

75:2 This is the proper position for the sovereign in his court, and for the sage as the teacher of the world. Khû accepts it in the latter capacity, but with dissatisfaction.

75:3 Compare the Lî Kî, Bk. XXXVIII, par. 10, et al.

75:4 As if he were one with the Tâo.

75:5 I do not see the appropriateness here of the

in the text.

in the text.

76:1 All these condemnatory descriptions of Yâo and Shun are eminently Tâoistic, but so metaphorical that it is not easy to appreciate them.

77:1 Compare the Tâo Teh King, ch. 3.

77:2 Khû is in all this too violent.

77:3 A disciple of Kang-sang Khû;--'a sincere seeker of the Tâo, very much to be pitied,' says Lin Hsî-kung.

78:1 The

in the former of these sentences is difficult. I take it in the sense of

in the former of these sentences is difficult. I take it in the sense of

, and read it phî.

, and read it phî.

78:2 Compare the Shih, II, v, Ode 2, 3.

78:3 I believe the fowls of Shan-tung are still larger than those of Kih-kiang or Fû-kien.

78:4 A good instance of Lao's metaphorical style.

79:1 In the text

. The

. The

must be an erroneous addition or probably it is a mistake for the speaker's name

must be an erroneous addition or probably it is a mistake for the speaker's name

.

.

79:2 Literally, 'between the eye-brows and eye-lashes.'

79:3 Thus we are as it were in the school of Lâo-dze, and can see how he deals with his pupils.

81:1 In this long reply there are many evident recognitions of passages in the Tâo Teh King;--compare chapters 9, 10, 55, 58.

81:2 See the description of Dze-khi's Tâoistic trance at the beginning of the second Book.

82:1 Nan-yung Khû disappears here. His first master, Käng-sang Khû, disappeared in paragraph 4. The different way in which his name is written by Sze-mâ Khien is mentioned in the brief introductory note on p. 153. It should have been further stated there that in the Fourth Book of Lieh-dze (IV, 2b-3b) some account of him is given with his name as written by Khien. A great officer of Khän is introduced as boasting of him that he was a sage, and, through his mastery of the principles of Lâo Tan, could hear with his eyes and see with his ears. Hereupon Khang-zhang is brought to the court of the marquis of Lû to whom he says that the report of him which he had heard was false, adding that he could dispense with the use of his senses altogether, but could not alter their several functions. This being reported to Confucius, he simply laughs at it, but makes no remark.

82:2 I suppose that from this to the end of the Book we have the sentiments of Kwang-dze himself. Whether we consider them his, or the teachings of Lao-dze to his visitor, they are among the depths of Tâoism, which I will not attempt to elucidate in the notes here.

82:3 The character which I have translated 'mind' here is

, meaning 'the side walls of a house,' and metaphorically used for 'the breast,' as the house of the mind. Hû explains it by

, meaning 'the side walls of a house,' and metaphorically used for 'the breast,' as the house of the mind. Hû explains it by

.

.

82:4 He is emancipated from the human as contrary to the heavenly.

82:5 The Tâo.

83:1 This Guardian of the Mind or Tower of Intelligence is the Tâo.

83:2 One of the rare introductions of spiritual agency in the early Tâoism.

84:1 That is, the will, man's own human element, in opposition to the Heavenly element of the Tâo.

84:2 One of the two famous swords made for Ho-lü, the king of Wû. See the account of their making in the seventy-fourth chapter of the 'History of the Various States;' very marvellous, but evidently, and acknowledged to be, fabulous.

86:1 Both Lâo and Kwang belonged to Khû, and this illustration was natural to them.

87:1 See in Bk. I, par. 2.

88:1 See on V, par. 2.

89:1 See Mencius V, i, 7.

89:2 Mencius V, i, 9.