Sacred Texts Legends/Sagas England Index Previous Next

The Lord of Misrule said to be peculiar to the English--A Court Officer--The Master of the King's Revels--The Lord of Misrule and his Conduct reprobated--The King of Christmas--of the Cockneys--A King of Christmas at Norwich--The King of the Bean--Whence originated--Christmastide in Charles I. Reign--The Boy-Bishop--Plough Monday--Shrove Tuesday--Easter Game--Hock-Tide--May-Games--The Lord and Lady of the May--Grand May-Game at Greenwich--Royal May-Game at Shooter's-hill--May Poles--May Milk-Maids--May Festival of the Chimney Sweepers--Whitsun-Games--Lamb Ale--The Vigil of Saint John the Baptist, how kept--Its supposed origin--Setting of the Midsummer Watch--Processions on Saint Clement's and Saint Catherine's day--Wassails--Sheep-shearing and Harvest-home--Wakes--Sunday Festivals--Church Ales--Funds raised by Church Ales--Fairs, and their diversions and abuses--Bonfires--Illuminations--Fireworks--Books on Fireworks--A Fiery Drake or Fiery Kite--London Fireworks--Fireworks on Tower-hill--at Public Gardens, and in Pageants.

THE LORD OF MISRULE PECULIAR TO ENGLAND.--It is said of the English, that formerly they were remarkable for the manner in which they celebrated the festival of Christmas; at which season they admitted variety of sports and pastimes not known, or little practised in other countries. 1 The mock prince, or lord of misrule, whose reign extended through the greater part of the holidays, is particularly remarked by foreign writers, who consider him as a personage rarely to be met with out of England; 2 and, two or three centuries back, perhaps this observation might be consistent with the truth; but I trust we shall upon due examination be ready to conclude, that anciently this frolicksome monarch was well known upon the continent, where he probably received his first honours. In this kingdom his power and his dignities suffered no diminution, but on the contrary were established by royal authority, and continued after they had ceased to exist elsewhere. But even with us his government has been extinct for many years, and his name and his offices are nearly forgotten. In some great families, and also sometimes at court, this officer was called the Abbot of Misrule. Leland says, "This Christmas 3 I saw no disguiseings at court, and right few playes; but there was an abbot of misrule that made much sport, and did right well his office." 4 In Scotland he was called the Abbot of Unreason, and prohibited there in 1555 by the parliament. 5

THE LORD OF MISRULE A COURT OFFICER.--Holingshed, speaking of Christmas, calls it, "What time there is alwayes one appointed to make sporte at courte called commonly lorde of misrule, whose office is not unknowne to such as have bene brought up in noblemen's houses and among great housekeepers, which use liberal feasting in the season." 6 Again: "At the feast of Christmas," says Stow, "in the king's court wherever he chanced to reside, there was

appointed a lord of misrule, or master of merry disports; the same merry fellow made his appearance at the house of every nobleman and person of distinction, and among the rest the lord mayor of London and the sheriffs had severally of them their lord of misrule, ever contending, without quarrel or offence, who should make the rarest pastimes to delight the beholders; this pageant potentate began his rule at All-hallow eve, and continued the same till the morrow after the Feast of the Purification; in which space there were fine and subtle disguisings, masks, and mummeries." 1

THE MASTER OF THE KING'S REVELS.--In the fifth year of Edward VI., at Christmas time, a gentleman named George Ferrers, who was a lawyer, a poet, and an historian, was appointed by the council to bear this office; "and he," says Holingshed, "being of better calling than commonly his predecessors had been before, received all his commissions and warrauntes by the name of master of the kinge's pastimes; which gentleman so well supplied his office, both of shew of sundry sights, and devises of rare invention, and in act of divers interludes, and matters of pastime, played by persons, as not only satisfied the common sorte, but also were verie well liked and allowed by the council, and others of skill in lyke pastimes; but best by the young king himselfe, as appeared by his princely liberalitie in rewarding that service."

THE LORD OF MISRULE--HIS CONDUCT REPROBATED.--This master of merry disports was not confined to the court, nor to the houses of the opulent, he was also elected in various parishes, where, indeed, his reign seems to have been of shorter date. Philip Stubbs, who lived at the close of the sixteenth century, places this whimsical personage, with his followers, in a very degrading point of view. 2 I shall give the passage in the author's own words, and leave the reader to comment upon them. "First of all, the wilde heades of the parish flocking togither, chuse them a graund captaine of mischiefe, whom they innoble with the title of Lord of Misrule; and him they crowne with great solemnity, and adopt for their king.. This king annoynted chooseth forth twentie, fourty, threescore, or an hundred lustie guttes, like to himself, to waite upon his lordly majesty, and to guarde his noble person. Then every one of these men he investeth with his liveries of greene, yellow, or some other light wanton colour, and as though they were not gawdy ynough, they bedecke themselves with scarffes, ribbons, and laces, hanged all over with gold ringes, pretious stones, and other jewels. This done, they tie aboute either legge twentie or fourtie belles, with riche handkerchiefes in their handes, and sometimes laide acrosse over their shoulders and neckes, borrowed, for the most part, of their pretie mopsies and loving Bessies. Thus all thinges set in order, then have they their hobby horses, their dragons, and other antiques, together with their baudie pipers, and thundring drummers, to strike up the devil's daunce with all. Then march this heathen company towards the church, their pypers pyping, their drummers thundring, their stumpes dauncing, their belles jyngling, their

handkerchiefes fluttering aboute their heades like madde men, their hobbie horses and other monsters skirmishing amongst the throng: and in this sorte they go to the church, though the minister be at prayer or preaching, dauncing and singing like devils incarnate, with such a confused noise that no man can heare his owne voyce. Then the foolish people they looke, they stare, they laugh, they fleere, and mount upon the formes and pewes to see these goodly pageants solemnized. Then after this, aboute the church they go againe and againe, and so fourthe into the churche yard, where they have commonly their sommer-halls, their bowers, arbours, and banquetting-houses set up, wherein they feast, banquet, and daunce all that day, and paradventure all that night too; and thus these terrestrial furies spend the sabbath day. Then, for the further innobling of this honourable lurdane, lord I should say, they have certaine papers wherein is painted some babelerie or other of imagerie worke, and these they call my Lord of Misrule's badges or cognizances. These they give to every one that will give them money to maintain them in this their heathenage devilrie, whordom, dronkennesse, pride, and whatnot. And who will not show himself buxome to them and give them money, they shall be mocked and flouted shamefully; yea, and many times carried upon a cowlstaffe, and dived over heade and eares in water, or otherwise most horribly abused. And so assotted are some, that they not only give them money, but weare their badges or cognizances in their hates or cappes openly. Another sorte of fantasticall fooles bring to these helhounds, the Lord of Misrule and his complices, some bread, some good ale, some new cheese, some old cheese, some custardes, some cracknels, some cakes, some flauns, some tartes, some creame, some meat, some one thing, and some another; but if they knewe that as often as they bring any to the maintenance of these execrable pastymes, they offer sacrifice to the Devill and Sathanas, they would refeus and withdrawe their handes, whiche God grant they maie." Hence it should seem the Lord of Misrule was sometimes president over the summer sports. The author has distinguished this pageantry from the May-games, the wakes, and the church-ales, of which, I should otherwise have thought, it might have been a component part.

* As a set-off to the extravagant condemnation of Stubbs, it may be well to state that the old English custom of the Christmas Lord of Misrule, with his twelve days of sovereignty, was maintained and supported by gentle folk of the highest position, who doubtless did their best to suppress the coarser elements. For instance, Richard Evelyn, a most worshipful squire and deputy-lieutenant of the counties of Surrey and Sussex, father of the author of the Diary, drew up regulations for appointing and defining the functions of this Christmas official on his Surrey estate at Wotton:--Imprimis, I give free leave to Owen Flood, my trumpeter, gentleman, to be Lord of Misrule of all good orders during the twelve days. And also I give free leave to the said Owen Flood to command all and every person or persons whatsoever, as well servants as others to be at his command whensoever he shall sound his trumpet or music, and to do him

good service, as though I were present myself, at their perils. . . . I give full power and authority to his lordship to break up all locks, bolts, bars, doors and latches, and to fling up all doors out of hinges, to come at those who presume to disobey his lordship's commands. God save the King."

* The various colleges both at Oxford and Cambridge elected a Christmas Lord, or Lord of Misrule, to preside over the sports, plays and pageants of the season. 1

THE KING OF CHRISTMAS.--The society belonging to Lincoln's Inn had anciently an officer chosen at this season, who was honoured with the title of King of Christmas Day, because he presided in the hall upon that day. This temporary potentate had a marshal and a steward to attend upon him. The marshal, in the absence of the monarch, was permitted to assume his state, and upon New Year's Day he sat as king in the hall when the master of the revels, during the time of dining, supplied the marshal's place. Upon Childermas Day they had another officer, denominated the King of the Cockneys, who also presided on the day of his appointment, and had his inferior officers to wait upon him. 2

A KING OF CHRISTMAS AT NORWICH.--In the history of Norfolk, 3 mention is made of a pageant exhibited at Norwich upon a Shrove Tuesday, which happened in the month of March, "when one rode through the street, having his horse trapped with tyn foyle and other nyse disgysynges, crowned as King of Christmas, in token that the season should end with the twelve moneths of the year; and afore hym went yche moneth dysgysyd as the season requiryd."

THE KING OF THE BEAN.--The dignified persons above mentioned were, I presume, upon an equal footing with the King of the Bean, whose reign commenced upon the vigil of the Epiphany, or upon the day itself. 4 We read that, some time back, "it was a common Christmas gambol in both our universities, and continued," at the commencement of the last century, "to be usual in other places, to give the name of king or queen to that person whose extraordinary good luck it was to hit upon that part of a divided cake which was honoured above the others by having a bean in it." 5 The reader will readily trace the vestige of this custom, though somewhat differently managed, and without the bean, in the present method of drawing, as it is called, for king and queen upon Twelfth-day. I will not pretend to say in ancient times, for the title is by no means of recent date, that the election of this monarch, the King of the Bean, depended entirely upon the decision of fortune: the words of an old kalendar belonging to the Romish church 6 seem to favour a contrary opinion; they are to this effect: On the fifth of January, the vigil of the Epiphany, the Kings of the Bean are created; 7 and on the sixth the feast of

the kings shall be held, and also of the queen; and let the banqueting be continued for many days. At court, in the eighth year of Edward III., this majestic title was conferred upon one of the king's minstrels, as we find by an entry in a computus so dated, which states that sixty shillings were given by the king, upon the day of the Epiphany, to Regan the trumpeter and his associates, the court minstrels, in the name of King of the Bean. 1

WHENCE THESE MOCK DIGNITIES WERE DERIVED.--Selden asserts, 2 and in my opinion with great justice, that all these whimsical transpositions of dignity are derived from the ancient Saturnalia, or Feasts of Saturn, when the masters waited upon their servants, who were honoured with mock titles, and permitted to assume the state and deportment of their lords. These fooleries were exceedingly popular, and continued to be practised long after the establishment of Christianity, in defiance of the threatenings and the remonstrances of the clergy, who, finding it impossible to divert the stream of vulgar prejudice, permitted their occasional exercise. The most daringly impious of such practices was the Festival of Fools, in which the most sacred rites and ceremonies of the church were turned into ridicule; but as this festival had happily very little and only short-lived hold on any part of England, it may be passed by.

An interesting condensed account of England's Christmastide in the days of Charles I. is worth citing:

"It is now Christmas, and not a Cup of drinke must passe without a Caroll, the Beasts, Fowle, and Fish come to a generall execution, and the Corne is ground to dust for the Bakehouse and the Pastry. Cards and Dice purge many a purse, and the Youth show their agility in Shoeing of the Wild Mare. 3 Now good cheere and welcome, and God be with you and I thanke you. And against the new yeare provide for the presents. The Lord of Mis-Rule is no meane man for his time, and the ghests of the High Table must lacke no Wine. The lusty bloods must looke about them like men, and piping and dauncing puts away much melancholy. Stolen Venison is sweet, and a fat Coney is worth money. Pitfalles are now set for small Birdes, and a Woodcocke hangs himselfe in a gynne. A good fire heats all the house, and a full Almesbasket makes the Beggars Prayers. The Masters and the Mummers make the merry sport; but if they lose their money, their Drumme goes dead. Swearers and Swaggerers are sent away to the Alehouse, and unruly Wenches goe in danger of Judgment. Musicians now make their Instruments speake out, and a good song is worth the hearing. In summe, it is a holy time, a duty in Christians, for the remembrance of Christ, and custome among friends, for the maintenance of good fellowship. In briefe, I thus conclude of it, I hold it (Christmas) a memory of

the Heaven's Love, and the world's peace, the myrth of the honest, and the meeting of the friendly. Farewell." 1

* THE BOY-BISHOP.--The election and the investment of the Boy-Bishop, a general English custom, was probably derived from the festival of fools. It does not appear at what period this curious ceremony was first established, but apparently it was ancient, at least we can trace it back to the thirteenth century. It had been long established at Salisbury in 1319, when Bishop Roger de Mortival specially regulated its observance.

* On the eve of St Nicholas's Day (December 5th), the most deserving chorister or scholar was appointed the bishop of boys until the end of the day of the Holy Innocents or Childermas (December 28th). The custom seems to have prevailed in all our cathedral churches, in the larger minster and monastic churches to which schools were attached, and in such purely scholastic foundations as those of the colleges of Winchester and Eton. Dean Colet, in his foundation of St Paul's School, desired to perpetuate this custom, as a stimulus to Christian ambition, and expressly orders that the scholars "shall, every Childermas, that is, Innocents' Day, come to Paule's churche, and hear the Childe Byshop's sermon, and after be at hygh masse, and each of them offer a penny to the childe byshop; and with them the maisters and surveyors of the schole." 2 Full episcopal vestments were provided for the Boy-Bishop, and copes for his companions; they occur in a great variety of inventories. At Salisbury, the Boy-Bishop and his fellows completely reversed the usual order of procession. The dean's residentiaries went first, followed by the chaplains, the bishops, and petty prebendaries. The choristers and their bishop came last; they sat in the upper stalls, the residentiaries furnished the incense and book, and the petties were the taper-bearers. The Boy-Bishop gave the benediction. Full Rubrical directions are given in the Sarum Processional for the Boy-Bishop during the few days that he held office. There is not the slightest touch of farce or ribaldry. 3 After divine service, the Boy-Bishop and his associates went about to different parts of the town, and visited the religious houses, collecting money. These ceremonies and processions were formally abrogated by proclamation from the king and council, in 1542, the thirty-third year of Henry VIII. The concluding clause of the ordinance runs thus: "Whereas heretofore dyvers and many superstitious and chyldysh observances have been used, and yet to this day are observed and kept in many and sundry places of this realm upon St Nicholas, St Catherines, St Clements, and Holy Innocents, and such like holydaies; children be strangelie decked and apparayled to counterfeit priests, bishops, and women, and so ledde with songs and dances from house to house, blessing the people, and gathering of money; and boyes do singe masse, and preache in the pulpits, with such other unfittinge and inconvenient usages, which tend rather to derysyon than enie true glorie to God, or honor of his

sayntes." 1 This idle pageantry was revived by his daughter Mary; and in the second year of her reign an edict, dated November 13, 1554, was issued from the Bishop of London to the clergy of his diocese, to have a Boy-Bishop in procession. 2 The year following, "the child bishop, of Paules church, with his company," were admitted into the queen's privy chamber, where he sang before her on Saint Nicholas' Day and upon Holy Innocents' Day. 3 Again the next year, says Strype, "on Saint Nicholas-even, Saint Nicholas, that is, a boy habited like a bishop in pontificalibus, 4 went abroad in most parts of London, singing after the old fashion; and was received with many ignorant but well-disposed people into their houses, and had as much good cheer as ever was wont to be had before."

* On the death of Mary this ancient custom was finally abandoned. The expression in Henry VIII.'s proclamation and elsewhere as to the Boy-Bishop "singing mass" must not be taken too literally; for though he aped much of the offices, the canon of the mass was certainly not sung by him, but only certain parts, such as the prose and offertory at Rouen.

* The elaborate account rolls of the great abbey of Durham for the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries show that the institution of Boy-Bishop was regularly observed there, year by year, with but few exceptions. It is stated in the hostillar's roll of 1405 that there was no Boy-Bishop that year because of the wars; the insurrection of the Percys had not then come to a close. There was an almery school at Durham in connection with the Infirmary, where the boys were daily fed and taught. The Boy-Bishop seems to have been chosen from these children, and is usually described in the accounts as Episcopus Elemosinariæ. He received gratuities from almost all the officers of the abbey, who entered the amount on their different rolls. These sums varied from 20d. to 5s. 5

* Richard Berde, doctor of laws, by will of May 2nd, 1501, left to the abbey church of the Austin Canons of St James, Northampton, his "mousterdevile hoode, with the lynyng of grene silk, for the cross-bearer on Seynt Nicholas-night." Doubtless the doctor, who had long had a chamber within the precincts, had often in his lifetime lent his parti-coloured hood for the festival of the monastery school. 6

* PLOUGH MONDAY.--There were three special seasons for the performance of what is termed English folk-drama, and traces of all three survive. They are the Christmas Mumming play, the Plough Monday play, and the Easter or Pace-Egg play. In all three the sword dance was usually introduced. The character of St George, and various forms of his legend, formed part of the Christmas and Easter play, but not of the intermediate one. Plough Monday, the Monday after Twelfth Day, was formerly kept throughout most parts of agricultural England by the ploughmen yoking themselves together and drawing

about a plough, accompanied by mummers and music. Their original object was to gather supplies in kind or money for the support of the Plough or Labourers' light in the parish church, and doubtless to use some part of the gathering for their own festivity or for a general Plough-Ale. But after the Reformation, when these special lights and gilds were suppressed, the tribute collected was spent entirely upon themselves. When the ploughboys came to any house of substance in the parish or district, the sword dance was executed, when one of the combatants was usually killed, and revived by a "doctor." Beelzebub or a fool, and one dressed extravagantly as a woman, and usually termed "Bessy," were two other of the characters. At the end of the mumming the money-box was rattled and the music played, and if neither refreshment nor money was forthcoming, the ground in front of the house, whether grass-plot or gravel walk, was roughly ploughed up, and the mummers departed. This last feature used to be vigorously carried out as late as the "forties" in the Peak of Derbyshire. 1 Plough Monday was observed in Huntingdonshire in 1860, where the mummers were termed "Plough-Witchers." 2 A Plough Monday play was acted at Wiverton Hall, Nottinghamshire, in 1893; no plough was brought round, but the mummers' clothes were ornamented with paper ploughs in red and black. 3

SHROVE TUESDAY.--Cock-fighting, and throwing at cocks on Shrove Tuesday, have been already mentioned, with other trifling sports which are comprised under their appropriate heads, and need not to be repeated. The day before Lent began used to be a universal holiday given up to a variety of sports. 4

* EASTER GAMES.--Easter, as has been already stated, was the usual season for an Easter play or mumming, which is still sometimes called the Pace-Egg play, a corruption of pasche or passover. The egg was always held to be an apt symbol of the Resurrection, hence Easter eggs and various customs that yet linger connected with them. This Easter play is still occasionally printed, 5 and occasionally acted by village players. The characters are much the same as they probably were in pre-Reformation days, namely, St George, Fool, Slasher, Doctor, Prince of Paradine, King of Egypt, Hector, Beelzebub, and Devil-Doubt. Occasionally the King of Egypt's daughter is introduced in character and not only mentioned. The play doubtless had a crusading origin.

HOCK-TIDE.--The popular holidays of Hock-tide, mentioned by Matthew Paris and other early writers, were kept on the Monday and Tuesday following the second Sunday after Easter Day; and distinguished, according to John Rouse, the Warwickshire historian of the fifteenth century, by various sportive

pastimes, in which the towns-people, divided into parties, were accustomed to draw each other with ropes. Spelman is more definite, and tells us, "they consisted in the men and women binding each other, and especially the women the men," and hence it was called Binding-Tuesday. 1 Cowel informs us that it was customary in several manors in Hampshire for "the men to hock the women on the Monday, and the women the men upon the Tuesday; that is, on that day the women in merriment stop the ways with ropes and pull the passengers to them, desiring something to be laid out in pious uses in order to obtain their freedom." 2 Such are the general outlines of this singular institution, and the pens of several able writers have been employed in attempting to investigate its origin. 3 Some think it was held in commemoration of the massacre of the Danes, in the reign of Ethelred the Unready, on Saint Brice's Day; 4 others, that it was in remembrance of the death of Hardicanute, which happened on Tuesday the 8th of June, 1041, by which event the English were delivered from the intolerant government of the Danes: and this opinion appears to be most probable. The binding part of the ceremony might naturally refer to the abject state of slavery in which the wretched Saxons were held by their imperious lords; and the donations for "pious uses," may be considered as tacit acknowledgments of gratitude to heaven for freeing the nation from its bondage. In the churchwarden's accounts for the parish of Lambeth for the years 1515 and 1516, are several entries of hock monies received from the men and the women for the church service. And here we may observe, that the contributions collected by the fair sex exceeded those made by the men. 5

Hock-day was generally observed as lately as the sixteenth century. We learn from Spelman that it was not totally discontinued in his time. Dr Plott, who makes Monday the principal day, has noticed some vestiges of it at the distance of fifty years, but now it is totally abolished.

* The derivation of the word Hock is still a puzzle to etymologists. 6 The roughly humorous games of this season, when the men extorted payment from the women on the Monday, and the women from the men on the Tuesday, are peculiar to England, whatever may be their historic origin, and were certainly in general use in the fourteenth century, and probably much earlier. The ransom money in olden times was usually handed over to the churchwardens. The large majority of extant parish accounts of pre-Reformation date have entries relative to Hock-tide payments.

MAY-GAMES.--The celebration of the May-games, at which we have only glanced in a former part of the work, 7 will require some enlargement in this chapter. "On the calends or first of May," says Bourne, 8 "commonly called May-day, the juvenile part of both sexes were wont to rise a little after midnight

and walk to some neighbouring wood, accompanied with music and blowing of horns, where they break down branches from the trees, and adorn them with nosegays and crowns of flowers; when this is done, they return with their booty homewards about the rising of the sun, and make their doors and windows to triumph with their flowery spoils; and the after part of the day is chiefly spent in dancing round a tall pole, which is called a May-pole; and being placed in a convenient part of the village, stands there, as it were, consecrated to the Goddess of Flowers, without the least violation being offered to it in the whole circle of the year."

This custom, no doubt, is a relic of one more ancient, practised by the Heathens, who observed the last four days in April, and the first of May, in honour of the goddess Flora. An old Romish calendar, cited by Mr Brand, says, on the 30th of April, the boys go out to seek May-trees, "Maii arbores a pueris exquirunter." Some consider the May-pole as a relic of Druidism; but I cannot find any solid foundation for such an opinion.

It should be observed, that the May-games were not always celebrated upon the first day of the month; and to this we may add the following extract from Stow: "In the month of May the citizens of London of all estates, generally in every parish, and in some instances two or three parishes joining together, had their several mayings, and did fetch their may-poles with divers warlike shows; with good archers, morrice-dancers, and other devices for pastime, all day long; and towards evening they had stage-plays and bonfires in the streets. These great mayings and May-games were made by the governors and masters of the city, together with the triumphant setting up of the great shaft or principal May-pole in Cornhill before the parish church of Saint Andrew," 1 which was thence called Saint Andrew Undershaft.

No doubt the May-games are of long standing, though the time of their institution cannot be traced. Mention is made of the May-pole at Cornhill, in a poem called the "Chaunce of the Dice," attributed to Chaucer. In the time of Stow, who died in 1605, they were not conducted with so great splendour as they had been formerly, owing to a dangerous riot which took place upon May-day, 1517, in the ninth year of Henry VIII., on which occasion several foreigners were slain, and two of the ringleaders of the disturbance were hanged.

Stow has passed unnoticed the manner in which the May-poles were usually decorated; this deficiency I shall supply from Philip Stubs, a contemporary writer, one who saw these pastimes in a very different point of view, and some may think his invectives are more severe than just; however, I am afraid the conclusion of them, though perhaps much exaggerated, is not altogether without foundation. He writes thus: 2 "Against Maie-day, Whitsunday, or some other time of the year, every parish, towne, or village, assemble themselves, both men, women, and children; and either all together, or dividing themselves into companies, they goe some to the woods and groves, some to the hills and mountaines,

some to one place, some to another, where they spend all the night in pleasant pastimes, and in the morning they return, bringing with them birche boughes and branches of trees to deck their assemblies withal. But their chiefest jewel they bring from thence is the Maie-pole, which they bring home with great veneration, as thus--they have twentie or fourtie yoake of oxen, every oxe having a sweete nosegaie of flowers tied to the tip of his hornes, and these oxen drawe home the May-poale, their stinking idol rather, which they covered all over with flowers and hearbes, bound round with strings from the top to the bottome, and sometimes it was painted with variable colours, having two or three hundred men, women, and children following it with great devotion. And thus equipped it was reared with handkerchiefes and flagges streaming on the top, they strawe the ground round about it, they bind green boughs about it, they set up summer halles, bowers, and arbours hard by it, and then fall they to banquetting and feasting, to leaping and dauncing about it, as the heathen people did at the dedication of their idolls. I have heard it crediblie reported, by men of great gravity, credite, and reputation, that of fourtie, threescore, or an hundred maides going to the wood, there have scarcely the third part of them returned home againe as they went."

In the churchwarden's account for the parish of St Helen's in Abingdon, Berks, dated 1566, the ninth of Elizabeth, is the following article: "Payde for setting up Robin Hoode's bower, eighteenpence;" that is, a bower for the reception of the fictitious Robin Hood and his company, belonging to the May-day pageant. 1

THE LORD AND LADY OF THE MAY.--It seems to have been the constant custom, at the celebration of the May-games, to elect a Lord and Lady of the May, who probably presided over the sports. On the thirtieth of May, 1557, in the fourth year of Queen Mary, "was a goodly May-game in Fenchurch Street, with drums, and guns, and pikes; and with the nine worthies who rode, and each of them made his speech, there was also a morrice dance, and an elephant and castle, and the Lord and Lady of the May appearing to make up the show." 2 We also read that the Lord of the May, and no doubt his Lady also, was decorated with scarfs, ribbands, and other fineries. Hence, in the comedy called The Knight of The Burning Pestle, written by Beaumont and Fletcher in 1611, a citizen, addressing himself to the other actors, says, "Let Ralph come out on May-day in the morning, and speak upon a conduit, with all his scarfs about him, and his feathers, and his rings, and his knacks, as Lord of the May." His request is complied with, and Ralph appears upon the stage in the assumed character, where he makes his speech, beginning in this manner:

[paragraph continues] The citizen is supposed to be a spectator, and Ralph is his apprentice, but permitted by him to play in the piece.

At the commencement of the sixteenth century, or perhaps still earlier, the ancient stories of Robin Hood and his frolicsome companions seem to have been new-modelled, and divided into separate ballads, which much increased their popularity; for this reason it was customary to personify this famous outlaw, with several of his most noted associates, and add them to the pageantry of the May-games. He presided as Lord of the May; and a female, or rather, perhaps, a man habited like a female, called the Maid Marian, his faithful mistress, was the Lady of the May. His companions were distinguished by the title of "Robin Hood's Men," and were also equipped in appropriate dresses; their coats, hoods, and hose were generally green. Henry VIII., in the first year of his reign, one morning, by way of pastime, came suddenly into the chamber where the queen and her ladies were sitting. He was attended by twelve noblemen, all apparelled in short coats of Kentish kendal, with hoods and hosen of the same; each of them had his bow, with arrows, and a sword, and a buckler, "like outlawes, or Robyn Hode's men." The queen, it seems, at first was somewhat afrighted by their appearance, of which she was not the least apprised. This gay troop performed several dances, and then departed. 1

Bishop Latimer, in a sermon which he preached before king Edward VI., relates the following anecdote, which proves the great popularity of the May pageants. "Coming," says he, "to a certain town on a holiday to preach, I found the church door fast locked. I taryed there half an houre and more, and at last the key was found, and one of the parish comes to me and sayes, Syr, this is a busy day with us, we cannot hear you; it is Robin Hoode's day; the parish are gone abroad to gather for Robin Hood; I pray you let 2 them not. I was fayne, therefore, to give place to Robin Hood. I thought my rochet would have been regarded; but it would not serve, it was faine to give place to Robin Hoode's men." 3 In Garrick's Collection of Old Plays 4 is one entitled "A new Playe of Robyn Hoode, for to be played in the May-games, very pleasaunte and full of Pastyme," printed at London by William Copland, black letter, without date. This playe consists of short dialogues between Robyn Hode, Lytell John, Fryer Tucke, a potter's boy, and the potter. Robyn fights with the friar, who afterwards becomes his chaplain; he also breaks the boy's pots, and commits several other absurdities. The language of the piece is somewhat low, and full of ribaldry. 5

GRAND MAY-GAME AT GREENWICH.--It has been observed that the May-games were not confined to the first day of the month, neither were they always concluded in one day; on the contrary I have now before me a manuscript, 6 written apparently in the reign of Henry VII., wherein a number of gentlemen, professing themselves to be the servants of the Lady May, promise to be in the

royal park at Greenwich, day after day, from two o'clock in the afternoon till five, in order to perform the various sports and exercises specified in the agreement; that is to say,

On the 14th day of May they engage to meet at a place appointed by the king, armed with the "harneis 1 thereunto accustomed, to kepe the fielde, and to run with every commer eight courses." Four additional courses were to be granted to any one who desired it, if the time would permit, or the queen was pleased to give them leave; agreeable to the ancient custom by which the ladies presided as arbitrators at the justs.

On the 15th the archers took the field to shoot at "the standard with flight arrows."

On the 16th they held a tournament with "swords rebated to strike with every commer eight strokes," according to the accustomed usage.

On the 18th, for I suppose Sunday intervened, they were to be ready to "wrestle with all commers all manner of ways," according to their pleasure.

On the 19th they were to enter the field, to fight on foot at the barriers, with spears in their hands and swords rebated by their sides, and with spear and sword to defend their barriers: there were to be eight strokes with the spear, two of them "with the foyne," or short thrust, and eight strokes with the sword; "every man to take his best advantage with gript or otherwise."

On the 20th they were to give additional proof of their strength by casting "the barre on foote, and with the arme, bothe heavit and hight." I do not clearly understand this passage, but suppose it means by lifting and casting aloft.

On the 21st they recommenced the exercises, which were to be continued daily, Sundays excepted, through the remaining part of May, and a fortnight in the month of June.

ROYAL MAY-GAME AT SHOOTER'S HILL.--Henry V III., when young, delighted much in pageantry, and the early part of his reign abounded with gaudy shows; most of them were his own devising, and others contrived for his amusement. Among the latter we may reckon a May-game at Shooter's Hill, which was exhibited by the officers of his guards; they in a body, amounting to two hundred, all of them clothed in green, and headed by their captain, who personated Robin Hood, met the King one morning as he was riding to take the air, accompanied by the queen and a large suite of the nobility of both sexes. The fictitious foresters first amused them with a double discharge of their arrows; and then, their chief approaching the king, invited him to see the manner in which he and his companions lived. The king complied with the request, and the archers, blowing their horns, conducted him and his train into the wood under the hill, where an arbour was made, with green boughs, having a hall, a great chamber, and an inner chamber, and the whole was covered with flowers and sweet herbs. When the company had entered the arbour, Robin Hood

excused the want of more abundant refreshment, saying to the king, "Sir, we outlaws usually breakfast upon venison, and have no other food to offer you." The king and queen then sat down, and were served with venison and wine; and after the entertainment, with which it seems they were well pleased, they departed, and on their return were met by two ladies riding in a rich open chariot, drawn by five horses. Every horse, according to Hollingshed, had his name upon his head, and upon every horse sat a lady, with her name written. On the first horse, called Lawde, sat Humidity; on the second, named Memeon, sat Lady Vert, or green; on the third, called Pheton, sat Lady Vegitive; on the fourth, called Rimphon, sat Lady Pleasaunce; on the fifth, called Lampace, sat Sweet Odour. 1 Both of the ladies in the chariot were splendidly apparelled; one of them personified the Lady May, and the other Lady Flora, "who," we are told, "saluted the king with divers goodly songs, and so brought him to Greenwich."

We may here just observe that the May-games had attracted the notice of the nobility long before the time of Henry; and agreeable to the custom of the times, no doubt, was the following curious passage in the old romance called The Death of Arthur: "Now it befell in the moneth of lusty May, that queene Guenever called unto her the knyghtes of the round table, and gave them warning that, early in the morning, she should ride on maying into the woods and fields beside Westminster." The knights were all of them to be clothed in green, to be well horsed, and every one of them to have a lady behind him, followed by an esquire and two yeomen, etc. 2

* MAY-POLES.--By an ordinance of the Long Parliament in April, 1644, all May-poles were to be taken down as "a heathenish vanity." The constables and churchwardens were to be fined 5s. weekly until the poles were removed. After the Restoration their use naturally revived. Hall wrote indignantly on the subject, in the bitterest Puritan vein, in a treatise that he called Funebria Flora, The Downfall of May Games, published in 1660. At the end he versifies, in "A May Pooles Speech to a Traveller," as follows:

[paragraph continues] The author states that "most of these May-poles are stollen, yet they give out that the poles are given them." In another place he says: If Moses were angry when he saw the people dancing about a golden calf, well may we be angry to see people dancing the morrice about a post in honour of a whore, as you shall see anon."

MAY MILK-MAIDS.--"It is at this time," that is, in May, says the author of one of the papers in the Spectator, 1 "we see the brisk young wenches, in the country parishes, dancing round the May-pole. It is likewise on the first day of this month that we see the ruddy milk-maid exerting herself in a most sprightly manner under a pyramid of silver tankards, and like the virgin Tarpeia, oppressed by the costly ornaments which her benefactors lay upon her. These decorations of silver cups, tankards, and salvers, were borrowed for the purpose, and hung round the milk-pails, with the addition of flowers and ribbands, which the maidens carried upon their heads when they went to the houses of their customers, and danced in order to obtain a small gratuity from each of them. In a set of prints called Tempest's Cryes of London, there is one called the merry milk-maid's, whose proper name was Kate Smith. She is dancing with the milk-pail, decorated as above mentioned, upon her head. 2 Of late years the plate, with the other decorations, were placed in a pyramidical form, and carried by two chairmen upon a wooden horse. The maidens walked before it, and performed the dance without any incumbrance. I really cannot discover what analogy the silver tankards and salvers can have to the business of the milk-maids. I have seen them act with much more propriety upon this occasion, when in place of these superfluous ornaments they substituted a cow. The animal had her horns gilt, and was nearly covered with ribbands of various colours, formed into bows and roses, and interspersed with green oaken leaves and bunches of flowers.

MAY FESTIVAL OF THE CHIMNEY-SWEEPERS.--The chimney-sweepers of London have also singled out the first of May for their festival; at which time they parade the streets in companies, disguised in various manners. Their dresses are usually decorated with gilt paper, and other mock fineries; they have their shovels and brushes in their hands, which they rattle one upon the other; and to this rough music they jump about in imitation of dancing. Some of the larger companies have a fiddler with them, and a Jack in the Green, as well as a Lord and Lady of the May, who follow the minstrel with great stateliness, and dance as occasion requires. The Jack in the green is a piece of pageantry consisting of a hollow frame of wood or wicker-work, made in the

form of a sugar-loaf, but open at the bottom, and sufficiently large and high to receive a man. The frame is covered with green leaves and bunches of flowers interwoven with each other, so that the man within may be completely concealed, who dances with his companions, and the populace are mightily pleased with the oddity of the moving pyramid.

WHITSUN GAMES.--The Whitsuntide holidays were celebrated by various pastimes commonly practised upon other festivals; but the Monday after the Whitsun week, at Kidlington in Oxfordshire, a fat lamb was provided, and the maidens of the town, having their thumbs tied behind them, were permitted to run after it, and she who with her mouth took hold of the lamb was declared the Lady of the Lamb, which, being killed and cleaned, but with the skin hanging upon it, was carried on a long pole before the lady and her companions to the green, attended with music, and a morisco dance of men, and another of women. The rest of the day was spent in mirth and merry glee. Next day the lamb, partly baked, partly boiled, and partly roasted, was served up for the lady's feast, where she sat, "majestically at the upper end of the table, and her companions with her," the music playing during the repast, which, being finished, the solemnity ended." 1

* LAMB-ALE.--Mr G. A. Rowell, in 1886, gave the following interesting and corrected account of this lamb-ale, which was held annually at Kirtlington (not Kidlington), a village about nine miles north of Oxford: 2

"The name of Kidlington is given for Kirtlington, the two villages being about four miles apart: the story of the maidens catching the lamb with their teeth is doubtless a mere made up tale, and I can only account for its having passed so long without contradiction from its apparent absurdity rendering it unnecessary for those of the neighbourhood. However, a description of the Kirtlington lamb-ale, and how it was conducted, may be interesting and set this question in a proper light. This I hope to do fairly, as my remembrance will go back over seventy years; and I am kindly assisted by a native, and long resident of the village, an observer, and well qualified to aid in the task.

The lamb-ale was held in a large barn, with a grass field contiguous for dancing, etc.; this was fitted up with great pains as a refreshment room for company (generally numerous) and was called 'My Lord's Hall.' The lord and lady, being the ruling persons, attending with their mace-bearers, or pages, and other officers. All were gaily and suitably dressed, with a preponderance of light blue and pink, the colours of the Dashwood family, the lady appearing in white only, with light blue or pink ribands on alternate days.

The lamb-ale began on Trinity Monday, when--and on each day at 11 A.M.--the lady was brought in state from her home, and at 9 P.M. was in like manner conducted home again; the sports were continued during the week, but Monday, Tuesday, and Saturday were the especial days.

The refreshments, as served, were not charged for; but a plate was afterwards

handed round for each to give his donation. This seems strikingly to accord with Aubrey's account of the Whitsun-ales of his grandfather's time.

The Morisco dance was not only a principal feature in the lamb-ale, but one for which Kirtlington was noted. No expense was spared in getting up as described in the paper on that subject; and with the liveries of the whitest and ribands of the best, the display of the Dashwood colours was the pride of the parish, and in my early times it was generally understood that the farmers' sons did not decline joining the dancers, but rather prided themselves on being selected as one of them. The simple tabor and pipe was their only music, but by degrees other instruments came into use in the private halls, and dancing on the green, and besides these the surroundings of stalls made up a sort of fair.

On opening the lamb-ale a procession was formed to take the lamb around the town and to the principal houses. It was carried on a man's shoulders or rather on the back of his neck with two legs on each side of it; the lamb being decorated with blue or pink ribands in accordance with the lady's colour of the day.

The great house was first visited, when after a few Morisco dances (as generally supposed) two guineas were given, and thus within the week every farm or other house of importance within the parish was visited. During the week there were various amusements; many hundreds visited the place from all sides, with a very general display of generosity and good will amongst all.

From about sixty or seventy years ago, the lamb used in the lamb-ale has been borrowed and returned; but previous to that time--for how long I cannot say--the lamb was slaughtered within the week, made into pies and distributed--but in what way is uncertain. It would be interesting if some light could be thrown on the lamb-ale. There is much which seems to connect it with the Whitsun-ale of early times; but, from the differences in the days and the possession of the lamb, there seems to be a wide distinction between the festivals.

As the lamb-ale appears to be unique, at least in this part of the country, an examination of the parish-registers might be interesting and throw some light on the subject."

MIDSUMMER EVE FESTIVAL.--On the Vigil of St John the Baptist, commonly called Midsummer Eve, it was usual in most country places, and also in towns and cities, for the inhabitants, both old and young, and of both sexes, to meet together, and make merry by the side of a large fire made in the middle of the street, or in some open and convenient place, over which the young men frequently leaped by way of frolic, and also exercised themselves with various sports and pastimes, more especially with running, wrestling, and dancing. These diversions they continued till midnight, and sometimes till cock-crowing; 1 several of the superstitious ceremonies practised upon this occasion are contained in the following verses, as they are translated by Barnabe Googe from the

fourth book of The Popish Kingdome, written in Latin by Tho. Neogeorgus: the translation was dedicated to queen Elizabeth, and appeared in 1570.

At London, in addition to the bonfires, "on the eve of this saint, as well as upon that of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, every man's door was shaded with green birch, long fennel, Saint John's wort, orpin, white lilies, and the like, ornamented with garlands of beautiful flowers. They, the citizens, had also lamps of glass with oil burning in them all night; and some of them hung out branches of iron, curiously wrought, containing hundreds of lamps lighted at once, which made a very splendid appearance." This information we receive from Stow, who tells us that, in his time, New Fish Street and Thames Street were peculiarly brilliant upon these occasions.

SUPPOSED ORIGIN OF THE MIDSUMMER VIGIL.--The reasons assigned for making bonfires upon the vigil of St John the Baptist in particular are various, for many writers have attempted the investigation of their origin; but unfortunately all their arguments, owing to the want of proper information, are merely hypothetical, and of course cannot be much depended upon. Those who suppose these fires to be a relic of some ancient heathenish superstition engrafted upon the variegated stock of ceremonies belonging to the Romish church, are not, in my opinion, far distant from the truth. The looking through the flowers at the fire, the casting of them finally into it, and the invocation to the Deity, with the effects supposed to be produced by those ceremonies, as mentioned in the preceding poem, are circumstances that seem to strengthen such a conclusion.

According to some of the pious writers of antiquity, they made large fires, which might be seen at a great distance, upon the vigil of this saint, in token that he was said in holy writ to be "a shining light." Others, agreeing with this, add also, these fires were made to drive away the dragons and evil spirits hovering in the air; and one of them gravely says, in some countries they burned bones, which was called a bone-fire; for "the dragons hattyd nothyng mor than the styncke of brenyng bonys." This, says another, habent ex gentilibus, they have from the heathens. The author last cited laments the abuses committed upon these occasions. "This vigil," says he, "ought to be held with cheerfulness and piety, but not with such merriment as is shewn by the profane lovers of

this world, who make great fires in the streets, and indulge themselves with filthy and unlawful games, to which they add glotony and drunkenness, and the commission of many other shameful indecencies." 1

SETTING OF THE MIDSUMMER WATCH.--In former times it was customary in London, and in other great cities, to set the Midsummer watch upon the eve of St John the Baptist; and this was usually performed with great pomp and pageantry. 2 The following short extract from the faithful historian, John Stow, will be sufficient to show the childishness as well as the expensiveness of this idle spectacle. The institution, he assures us, had been appointed, "time out of mind;" and upon this occasion the standing watches "in bright harness." There was also a marching watch, that passed through all the principal streets. In order to furnish this watch with lights, there were appointed seven hundred cressets; the charge for every cresset was two shillings and fourpence; every cresset required two men, the one to bear it, and the other to carry a bag with light to serve it. The cresset was a large lanthorn fixed at the end of a long pole, and carried upon a man's shoulder. The cressets were found partly by the different companies, and partly by the city chamber. Every one of the cresset-bearers was paid for his trouble; he had also given to him, that evening, a strawen hat and a painted badge, besides the donation of his breakfast next morning. The marching watch consisted of two thousand men, most of them being old soldiers of every denomination. They appeared in appropriate habits, with their arms in their hands, and many of them, especially the musicians and the standard-bearers, rode upon great horses. There were also divers pageants and morris-dancers with the constables, one half of which, to the amount of one hundred and twenty, went out on the eve of Saint John, and the other half on the eve of Saint Peter. The constables were dressed in "bright harnesse, some over gilt, and every one had a joinet of scarlet thereupon, and a chain of gold; his henchman following him, and his minstrels before him, and his cresset-light at his side. The mayor himself came after him, well mounted, with his sword-bearer before him, in fair armour on horseback, preceded by the waits, or city minstrels, and the mayor's officers in liveries of worsted, or say jackets party-coloured. The mayor was surrounded by his footmen and torch-bearers, and followed by two henchmen on large horses. The sheriffs' watches came one after the other in like order, but not so numerous; for the mayor had, besides his giant, three pageants; whereas the sheriffs had only two besides their giants, each with their morris-dance and one henchman: their officers were clothed in jackets of worsted, or say party-coloured, but differing from those belonging to the mayor, and from each other: they had also a great number of harnessed men." 3 This old custom of setting the watch in London was maintained until the year 1539, in the 31st year of Henry VIII. when it was discontinued on

account of the expense, and revived in the year 1548, the 2d of Edward VI. and soon after that time it was totally abolished.

On Midsummer eve it was customary annually at Burford, in Oxfordshire, to carry a dragon up and down the town, with mirth and rejoicing; to which they also added the picture 1 of a giant. Dr Plott tells us, this pageantry was continued in his memory, and says it was established, at least the dragon part of the show, in memory of a famous victory obtained near that place, about 750, by Cuthred, king of the west Saxons, over Ethebald, king of Mercia, who lost his standard, surmounted by a golden dragon, 2 in the action.

PROCESSIONS ON ST CLEMENT'S AND ST CATHERINE'S DAYS.--The Anniversary of Saint Clement, and that of Saint Catherine, the first upon the 23rd, and the second upon the 25th, of November, were formerly particularised by religious processions which had been disused after the Reformation, but again established by Queen Mary. In the year she ascended the throne, according to Strype, on the evening of Saint Catherine's Day, her procession was celebrated at London with five hundred great lights, which where carried round Saint Paul's steeple; 3 and again three years afterwards, her image, if I clearly understand my author, was taken about the battlements of the same church with fine singing and many great lights. 4 But the most splendid show of this kind that took place in Mary's time was the procession on Saint Clement's Day, exhibited in the streets of London; it consisted of sixty priests and clerks in their copes, attended by divers of the inns of court, who went next the priests, preceded by eighty banners and streamers, with the waits or minstrels of the city playing upon different instruments. 5

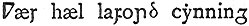

WASSAILS.--Wassail, or rather the wassail bowl, which was a bowl of spiced ale, formerly carried about by young women on New-year's eve, who went from door to door in their several parishes singing a few couplets of homely verses composed for the purpose, and presented the liquor to the inhabitants of the house where they called, expecting a small gratuity in return. Selden alludes to this custom in the following comparison: "The Pope, in sending reliques to princes, does as wenches do by their wassails at New-year's tide, they present you with a cup, and you must drink of a slabby stuff; but the meaning is, you must give them monies ten times more than it is worth." The wassail is said to have originated from the words of Rowena, the daughter of Hengist; who, presenting a bowl of wine to Vortigern, the king of the Britons, said, Wæs hæl, or, Health to you, my lord the king; (

[Ðær hæl larond cẏnninȝ]). If this derivation of the custom should be thought doubtful, I can only say that it has the authority at least of antiquity on its side. The wassails are now (1800) quite obsolete; but it seems that fifty years back, some vestiges of them were remaining in Cornwall; but the time of their performance was changed to twelfth-day. 6

[Ðær hæl larond cẏnninȝ]). If this derivation of the custom should be thought doubtful, I can only say that it has the authority at least of antiquity on its side. The wassails are now (1800) quite obsolete; but it seems that fifty years back, some vestiges of them were remaining in Cornwall; but the time of their performance was changed to twelfth-day. 6

* The custom of carrying round the wassail bowl at Christmastide seems to have long ago disappeared, though the following verse is still (1902) occasionally sung by children when "carolling" in the west of England:

* Wassailing the orchards may possibly survive in the apple-growing districts, but tit seems doubtful if it is anything more than boys shouting rhymes round the trees on Twelfth Night. In the "fifties" of the last century, it was not infrequent on the Somersetshire side of Exmoor. A great bowl of cider was placed in one of the biggest trees after dark. When the verses of incantation had been sung, each of the company drank from the bowl, and the remainder was flung up into the tree. 1

* A correspondent of Notes and Queries contributed the following in 1852:

"In this neighbourhood (Chailey, Sussex) the custom of wassailing the orchards still remains. It is called apple-howling. A troop of boys visit the different orchards, and encircling the apple-trees they repeat the following words:

They then shout in chorus, one of the boys accompanying them on the cow's horn; during the ceremony they rap the trees with their sticks. 2

* In Hazlitt's edition of Brand's Popular Antiquities, published in 1870, the shouting of the boys in the orchards is said to still prevail in several counties.

SHEEP-SHEARING AND HARVEST-HOME.--There are two feasts annually held among the farmers of this country, which are regularly made in the spring, and at the end of the summer, or the beginning of autumn, but not confined to any particular day. The first is the sheep-shearing, and the second the harvest-home; both of them were celebrated in ancient times with feasting and variety of rustic pastimes; at present (1800), excepting a dinner, or more frequently a supper, at the conclusion of the sheep-shearing and the harvest, we have little remains of the former customs.

The particular manner in which the sheep-shearing was celebrated in old time is not recorded; but respecting the harvest-home we meet with several curious observations. Hentzner, a foreign gentleman, who was in England at the close of the sixteenth century, and wrote an account of what he saw here,

says, "as we were returning to our inn (in or near Windsor), we happened to meet some country people celebrating their harvest-home: their last load of corn they crown with flowers, having besides an image richly dressed, by which, perhaps, they signify Ceres; this they keep moving about, while the men and women, and men and maid-servants, riding through the streets in the cart, shout as loud as they can till they arrive at the barn." Moresin, another foreign writer, also tells us that he saw "in England, the country people bring home," from the harvest field, I presume he means, "a figure made with corn, round which the men and the women were promiscuously singing, and preceded by a piper or a drum." 1 "In the north," says Mr Brand, "not half a century ago, they used everywhere to dress up a figure something similar to that just described, at the end of harvest, which they called a kern-baby, plainly a corruption of corn-baby, as the kern, or churn supper, is of corn-supper." 2

The harvest-supper in some places is called a mell-supper, and a churn-supper. Mell is plainly derived from the French word mesler, to mingle together, the master and servant promiscuously at the same table. 3 At the mell-supper, Bourne 4 tells us, "the servant and his master are alike, and every thing is done with equal freedom. They sit at the same table, converse freely together, and spend the remaining part of the night in dancing and singing, without any difference or distinction." "There was," continues my author," a custom among the heathens much like this at the gathering of their harvest, when the servants were indulged with their liberty, and put upon an equality with their masters for a certain time. Probably both of them originated from the Jewish feast of tabernacles." 5

WAKES.--The wakes, when first instituted in this country, were established upon religious principles, and greatly resembled the agapæ, or love feasts of the early Christians. It seems, however, clear that they derived their origin from some more ancient rites practised in the times of paganism. Hence Pope Gregory, in his letter to Melitus, a British abbot, says, "whereas the people were accustomed to sacrifice many oxen in honour of dæmons, let them celebrate a religious and solemn festival, and not slay the animals, diabolo, to the devil, but to be eaten by themselves, ad laudem Dei, to the praise of God." 6 These festivals were primitively held upon the day of the dedication of the church in each district, or the day of the saint whose relics were therein deposited, or to whose honour it was consecrated; for which purpose the people were directed to make booths and tents with the boughs of trees adjoining to the churches, 7 and in them to celebrate the feast with thanksgiving and prayer. In process of time the people assembled on the vigil, or evening preceding the saint's day, and came, says an old author, "to churche with candellys burnyng, and would

wake, and come toward night to the church in their devocion," 1 agreeable to the requisition contained in one of the canons established by King Edgar, whereby those who came to the wake were ordered to pray devoutly, and not to betake themselves to drunkenness and debauchery. The necessity for this restriction plainly indicates that abuses of this religious institution began to make their appearance as early as the tenth century. The author above cited goes on, "and afterwards the pepul fell to letcherie, and songs, and daunses, with harping and piping, and also to glotony and sinne; and so tourned the holyness to cursydness; wherefore holy faders ordeyned the pepull to leve that waking and to fast the evyn, but it is called vigilia, that is waking, in English, and eveyn, for of eveyn they were wont to come to churche." In proportion as these festivals deviated from the original design of their institution, they became more popular, the conviviality was extended, and not only the inhabitants of the parish to which the church belonged were present at them, but they were joined by others from the neighbouring towns and parishes, who flocked together upon these occasions, and the greater the reputation of the tutelar saint, the greater generally was the promiscuous assembly. The pedlars and hawkers attended to sell their wares, and so by degrees the religious wake was converted into a secular fair, and the time was spent in festive mirth and vulgar amusements.

SUNDAY FESTIVALS.--"In the northern parts of this nation," says Bourne, "the inhabitants of most country villages are wont to observe some Sunday in a more particular manner than the other common Sundays of the year, namely, the Sunday after the day of dedication of their church," that is, the Sunday after the saint's day to whom the church was dedicated. "Then the people deck themselves in their gaudiest clothes, and have open doors and splendid entertainments for the reception and treating of their relations and friends, who visit them on that occasion from each neighbouring town. The morning is spent for the most part at church, though not as that morning was wont to be spent, with the commemoration of the saint or martyr; nor the grateful remembrance of the builder and endower." Being come from church, the remaining part of the day is spent in eating and drinking, and so is a day or two afterwards, together with all sorts of rural pastimes and exercises, such as dancing on the green, wrestling, cudgelling, and the like. "In the northern parts, the Sunday's feasting is almost lost, and they observe only one day for the whole, which among them is called hopping, I suppose from the dancing and other exercises then practised. Here they used to end many quarrels between neighbour and neighbour, and hither came the wives in comely manner, and they which were of the better sort had their mantles carried with them, as well for show as to keep them from the cold at the table. These mantles also many did use at the churches, at the morrow masses, and at other times." 2

CHURCH-ALES.--The Church-ales, called also Easter-ales, and Whitsun-

ales from their being sometimes held on Easter-Sunday, and on Whit-Sunday, or on some of the holidays that follow them, certainly originated from the wakes. The churchwardens and other chief parish officers, observing the wakes to be more popular than any other holidays, rightly conceived, that by establishing other institutions somewhat similar to them, they might draw together a large company of people, and annually collect from them, such sums of money for the support and repairs of the church, as would be a great easement to the parish rates. By way of enticement to the populace they brewed a certain portion of strong ale, to be ready on the day appointed for the festival, which they sold to them; and most of the better sort, in addition to what they paid for their drink, contributed something towards the collection; but in some instances the inhabitants of one or more parishes were mulcted in a certain sum according to mutual agreement, as we find by an ancient stipulation, 1 couched in the following terms: "The parishioners of Elvaston and those of Okebrook in Derbyshire agree jointly to brew four ales, and every ale of one quarter of malt between this, and the feast of Saint John the Baptist next comming, and every inhabitant of the said town of Okebrook shall be at the several ales; and every husband and his wife shall pay two pence, and every cottager one penny. And the inhabitants of Elvaston shall have and receive all the profits comming of the said ales, to the use and behoof of the church of Elvaston; and the inhabitants of Elvaston shall brew eight ales betwixt this and the feast of Saint John, at which ales the inhabitants of Okebrook shall come and pay as before rehearsed; and if any be away one ale, he is to pay at t’oder ale for both." In Cornwall the church-ales were ordered in a different manner; for there two young men of a parish were annually chosen by their foregoers to be wardens, "who, dividing the task, made collections among the parishioners of whatever provision it pleased them to bestow; this they employed in brewing, baking, and other acates, against Whitsontide, upon which holidaies the neighbours meet at the church-house, and there merely feed on their own victuals, contributing some petty portion to the stock. When the feast is ended, the wardens yield in their accounts to the parishioners; and such money as exceedeth the disbursements, is layed up in store to defray any extraordinary charges arising in the parish." 2

To what has been said upon this subject, I shall only add the following extract from Philip Stubbs, an author before quoted, who lived in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, whose writings 3 are pointed against the popular vices and immoralities of his time. "In certaine townes," says he, "where drunken Bacchus bears swaie against Christmass and Easter, Whitsunday, or some other time, the churchwardens, for so they call them, of every parish, with the consent of the whole parish, provide half a score or twentie quarters of mault, whereof some they buy of the church stocke, and some is given to them of the

parishioners themselves, every one conferring somewhat, according to his ability; which mault being made into very strong ale, or beer, is set to sale, either in the church or in some other place assigned to that purpose. Then, when this nippitatum, this huffe-cappe, as they call it, this nectar of life, is set abroach, well is he that can get the soonest to it, and spends the most at it, for he is counted the godliest man of all the rest, and most in God's favour, because it is spent upon his church forsooth. If all be true which they say, they bestow that money which is got thereby for the repaire of their churches and chappels; they buy bookes for the service, cupps for the celebration of the sacrament, surplesses for Sir John, and such other necessaries," etc. He then proceeds to speak upon "the manner of keeping wakesses (wakes) in England," in a style similar to that above cited, and says they were "the sources of gluttonie and drunkenness"; and adds, "many spend more at one of these wakesses than in all the whole years besides."

The ingenious researcher into the causes of melancholy on the contrary thinks that these kinds of amusement ought not to be denied to the commonalty. 1 Chaucer, in the Ploughman's Tale, reproves the priests because they were more attentive to the practice of secular pastimes than to the administration of their holy functions, saying they were expert

FAIRS.--The church-ales have long been discontinued; the wakes are still kept up in the northern parts of the kingdom; but neither they nor the fairs maintain their former importance; many of both, and most of the latter, have dwindled into mere markets for petty traffic, or else they are confined to the purposes of drinking, or the displayment of vulgar pastimes. These pastimes, or at least such of them as occur to my memory, I shall mention here in a cursory manner, and pass on to the remaining part of this chapter. In a paper belonging to the Spectator 2 there is a short description of a country wake. "I found," says the author, "a ring of cudgel-players, who were breaking one another's heads in order to make some impression on their mistresses' hearts." He then came to "a foot-ball match," and afterwards to "a ring of wrestlers." Here he observes, "the squire of the parish always treats the company every year with a hogshead of ale, and proposes a beaver hat as a recompence to him who gives the most falls." The last sport he mentions is pitching the bar. But he might, and with great propriety, have added most of the games in practice among the lower classes of the people that have been specified in the foregoing pages, and perhaps the whistling match recorded in another paper. "The prize," we are told, "was one guinea, to be conferred upon the ablest whistler; that is, he that could whistle clearest, and go through his tune without laughing, to which at

the same time he was provoked by the antic postures of a merry-andrew, who was to stand upon the stage, and play his tricks in the eye of the performer. There were three competitors; the two first failed, but the third, in defiance of the zany and all his arts, whistled through two tunes with so settled a countenance that he bore away the prize, to the great admiration of the spectators." This paper was written by Addison, who assures us he was present at the performance, which took place at Bath about the year 1708. To this he adds another curious pastime, as a kind of Christmas gambol, which he had seen also; that is, a yawning match for a Cheshire cheese: the sport began about midnight, when the whole company were disposed to be drowsy; and he that yawned the widest, and at the same time most naturally, so as to produce the greatest number of yawns from the spectators, obtained the cheese.

The barbarous and wicked diversion of throwing at cocks usually took place at all the wakes and fairs that were held about Shrovetide, and especially at such of them as were kept on Shrove-Tuesday. Upon the abolition of this inhuman custom, the place of the living birds was supplied by toys made in the shape of cocks, with large and heavy stands of lead, at which the boys, on paying some very trifling sum, were permitted to throw as heretofore; and he who could overturn the toy claimed it as a reward for his adroitness. This innocent pastime never became popular, for the sport derived from the torment of a living creature existed no longer, and its want was not to be compensated by the overthrowing or breaking a motionless representative; therefore the diversion was very soon discontinued.

At present, snuff-boxes, tobacco-boxes, and other trinkets of small value, or else halfpence or gingerbread, placed upon low stands, are thrown at, and sometimes apples and oranges, set up in small heaps; and children are usually enticed to lay out their money for permission to throw at them by the owners, who keep continually bawling, "Knock down one you have them all." A half-penny is the common price for one throw, and the distance about ten or twelve yards.

The Jingling Match is a diversion common enough at country wakes and fairs. The performance requires a large circle, enclosed with ropes, which is occupied by as many persons as are permitted to play. They rarely exceed nine or ten. All of these, except one of the most active, who is the jingler, have their eyes blinded with handkerchiefs or napkins. The eyes of the jingler are not covered, but he holds a small bell in each hand, which he is obliged to keep ringing incessantly so long as the play continues, which is commonly about twenty minutes, but sometimes it is extended to half an hour. In some places the jingler has also small bells affixed to his knees and elbows. His business is to elude the pursuit of his blinded companions, who follow him, by the sound of the bells, in all directions, and sometimes oblige him to exert his utmost abilities to effect his escape, which must be done within the boundaries

of the rope, for the laws of the sport forbid him to pass beyond it. If he be caught in the time allotted for the continuance of the game, the person who caught him claims the prize: if, on the contrary, they are not able to take him, the prize becomes his due.

Hunting the Pig is another favourite rustic pastime. The tail of the animal is previously cut short, and well soaped, and in this condition he is turned out for the populace to run after him; and he who can catch him with one hand, and hold him by the stump of the tail without touching any other part, obtains him for his pains.

Sack Running, that is, men tied up in sacks, every part of them being enclosed except their heads, who are in this manner to make the best of their way to some given distance, where he who first arrives obtains the prize.

Smock Races are commonly performed by the young country wenches, and so called because the prize is a holland smock, or shift, usually decorated with ribbands. 1

The Wheelbarrow Race requires room, and is performed upon some open green, or in a field free from encumbrances. The candidates are all of them blindfolded, and every one has his wheelbarrow, which he is to drive from the starting-place to a mark set up for that purpose, at some considerable distance. He who first reaches the mark of course is the conqueror. But this task is seldom very readily accomplished; on the contrary, the windings and wanderings of these droll knights-errant, in most cases, produce much merriment.

The Grinning Match is performed by two or more persons endeavouring to exceed each other in the distortion of their features, every one of them having his head thrust through a horse's collar.

Smoking Matches are usually made for tobacco-boxes, or some other trifling prizes, and may be performed two ways: the first is a trial among the candidates who shall smoke a pipe full of tobacco in the shortest time: the second is precisely the reverse; for he of them who can keep the tobacco alight within his pipe, and retain it there the longest, receives the reward.

To these we may add the Hot Hasty-pudding Eaters, who contend for superiority by swallowing the greatest quantity of hot hasty-pudding in the shortest time; so that he whose throat is widest and most callous is sure to be the conqueror.

The evening is commonly concluded with singing for laces and ribbands, which divertisement indiscriminately admits of the exertions of both sexes.

BONFIRES.--It has been customary in this country, from time immemorial, for the people, upon occasions of rejoicing, or by way of expressing their approbation of any public occurrence, to make large bonfires upon the close of the day, to parade the street with great lights, and to illuminate their houses.