Sacred Texts Earth Mysteries Index Previous Next

WITH THE Symmes Theory of Concentric Spheres we take up, for the first time, a cosmogony of the nineteenth century. In this flight through worlds we have spanned not only the centuries but the oceans and continents of the Earth. We are in the year of our Lord, 1818, in America, and at St. Louis, Missouri, on the western bank of the mightiest river of the Earth. We are on the continent whose aboriginal inhabitants have, running through all their mythologies and traditions, the tradition and myth of a "hollow Earth," and we are about to consider, in their order, three modern American theories of the figure of Earth, all of them based on the assumption that this planet is a hollow sphere, habitable within.

A brief circular announced the first of these:

Light gives light to light discover--ad infinitum

St. Louis (Missouri Territory)

NORTH AMERICA, April 10, A.D., 1818

TO ALL THE WORLD:

I declare that the earth is hollow and habitable within; containing a number of solid concentric spheres, one

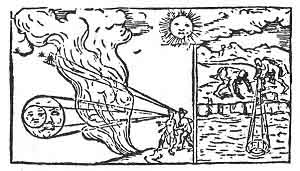

Click to enlarge

PLATE XLII. THE THREE WORLD OCTAVES

(From Utriusque Cosmi; Robert Fludd, 1621. Vol. I)

within the other, and that it is open at the poles twelve or sixteen degrees. I pledge my life in support of this truth, and am ready to explore the hollow, if the world will support and aid me in this undertaking.

JNO. CLEVES SYMMES

Of Ohio, late Captain of Infantry.

N. B. I have ready for the press a Treatise on the Principles of the matter, wherein I show proofs of the above position, account for the various phenomena, and disclose Dr. Darwin's "Golden Secret."

I ask one hundred brave companions, well equipped, to start from Siberia in the fall season, with reindeer and sleighs, on the ice of the frozen sea; and I engage we find a warm and rich land, stocked with thrifty vegetables and animals, if not men, on reaching one degree northwest of latitude 62; we will return in the succeeding spring.

J. C. S.

Symmes never reached, nor even began his journey to reach, the "north polar Verge of the world," let pass its interior. In 1822 and again in 1823, he petitioned the Congress of the United States to equip for him two vessels "of 250 or 300 tons burden," and in 1824 even sought aid from the General Assembly of the State of Ohio. Naturally no such request was even considered by an American Congress or Legislature. In 1829 he died, and over his grave, at Hamilton, Ohio, was erected a monument surmounted by a hollow globe open at the poles, inscribed: "He contended that the Earth is hollow and habitable within."

Where Symmes got his notion that the Earth has a concave,

habitable surface seems to have interested nobody. But it is interesting to consider that three "concave" cosmogonies have sprung up within less than a century on this continent whose aborigines believed in the hollowness of their "great Island." The Montagnais held the earth to be pierced through and through; that the Sun set by entering one hole and hiding inside the Earth during the night; that it rose by emerging from the opposite hole. Numberless tribes have the tradition that formerly their race lived underground, until some adventurous youth climbed upwards by some great vine to the outer surface of the Earth, and, finding it delightful and habitable, returned and brought their people out of the "concave." Indian gods fell from Heaven, through the Earth; and vanished races were those who had returned to their first homes. How much of this Symmes had picked up through fraternising with the western Indians, or whether he had ever heard any of this tradition from them, we shall probably never know.

In 1826, "A Citizen of the United States," otherwise James McBride, published, at Cincinnati, a little book called The Symmes Theory of Concentric Spheres, giving thesis and proofs.

"According to Symmes's Theory, the earth, as well as all the celestial orbicular bodies existing in the universe, visible and invisible, which partake in any degree of a planetary nature, from the greatest to the smallest, from the sun down to the most minute blazing meteor or falling star, are all constituted in a greater or less degree, of a collection of spheres, more or less solid, concentric with each

Click to enlarge

PLATE XLIII. THE SYMMES THEORY OF CONCENTRIC SPHERES

(From The Symmes Theory of Concentric Spheres, compiled by Americus Symmes, 1878)

other, and more or less open at their poles; each sphere being separated from its adjoining compeers by space replete with aerial fluids; that every portion of infinite space, except what is occupied by spheres, is filled with an aerial elastic fluid, more subtle than common atmospheric air; and constituted of innumerable small concentric spheres, too minute to be visible to the organ of sight assisted by the most perfect microscope, and so elastic that they continually press on each other, and change their relative situations as often as the position of any piece of matter in space may change its position; thus causing a universal pressure, which is weakened by the intervention of other bodies in proportion to the subtended angle of distance and dimension; necessarily causing the body to move towards the points of decreased pressure."

Symmes believed that the planet "which has been designated the Earth," is composed of at least five concentric spheres, with spaces between each, an atmosphere surrounding each, and each habitable upon both its surfaces. Each sphere was widely open at its poles, and the north polar opening of the outer sphere whose convex surface man inhabits, he believed to be about four thousand miles in diameter. The southern polar opening he estimated to be half again as large.

Each of the spheres composing the Earth is according to this theory lighted and warmed "according to those general laws which communicate light and heat to every part of the universe." This light and heat might not be so bright or so intense as ours; and the probability of this is indicated, he says, in those high northern latitudes, where

the "Verge" begins, by the paleness of the Sun and the darkness of the sky; yet he does not doubt that they are sufficiently warmed and lighted to support animal and vegetable life.

His "mid-plane-space" theory is interesting, and Gardner's diagram (Plate XLIV) makes it very clear. Each sphere has a cavity, or mid-plane-space near its centre--the medial line, that is, which would split its crust or shell into inner and outer layers--filled with this light, subtle, elastic aerial fluid, "partaking somewhat of the nature of hydrogen gas; which aerial fluid is composed of molecules greatly rarefied in comparison with the gravity of the extended or exposed surfaces of the sphere." It is this mid-plane-space which gives the sphere lightness and buoyancy, and the aerial fluid with which it is filled may possibly, he conjectures, serve for the support of animal life.

Clouds formed in the outer air of the planet would probably float through the vast polar openings in the form of rain or snow. The great winds or typhoons, known on the Earth, might have their force supplied by winds sucked into one polar opening, and emerging through the other, thus performing the circuit of the sphere.

He argues his hollow Earth by analogy--to hollow stalks of wheat, the hollow quills and feathers of birds, the hollow bones of animals, and the hollow hairs of our heads. This would be, he says, "the most perfect system of creative economy, a great saving of stuff." And, this early in the history of north polar exploration, and from the evidence of whalers and fishermen in the northern seas regarding

Click to enlarge

PLATE XLIV. GARDNER'S DIAGRAM OF SYMMES'S EARTH

Showing the five concentric spheres, with their polar openings at the Verges of the World. their separating atmospheres, and their mid-plane spaces.

(From A Journey to the Earth's Interior; Marshall B. Gardner, 1920)

the migration of birds, animals, and fish to and from the north polar zone, he is arguing for a warm and habitable region beyond the ice-packs, "where the fresh waters furiously contend with the salt." He develops at great length the precise manner in which light and heat from our Sun might, by reflection and refraction, penetrate into every part of the interior shells. It is even possible, he suggests, that, "near the Verges of the polar openings, and perhaps in many other parts of the unfathomable ocean, the spheres are water quite through (at least all except the mid-plane-spaces or cavities), which being the case, light would probably be transmitted through the spheres."

Symmes believed that man, in his efforts to reach the North Pole, had always failed just on the "Verge"; that once past the ice barrier and headed inevitably for the interior of the hollow shell, he would find himself almost at once in a temperate zone. The path to the interior, he says, would be a tortuous one, by way of "the winding meridians of the Verge."

THE KORESHAN COSMOGONY is another "hollow Earth" theory, which was first given out in 1870 by Cyrus Reed Teed. The chart given in Plate XLV contains all the principal diagrams by which the theory is illustrated.

This second of modern American cosmogonies holds that the Earth we live upon and think we "know" to be the

outer surface of a sphere, is, in reality, its concave surface; that we are actually living enclosed within a hollow shell, however much our collective senses and our collective science seem to prove the contrary. This, Teed affirms, is because we have been taught for centuries that the Earth is a globe filled with molten matter on whose cooled crust we live; that it is but a speck in infinite Space, a dot in a vast ocean of worlds, revolving on its own axis every twenty-four hours and thus creating its own days and nights in its yearly revolutions around the Sun; that the Moon shines a borrowed light; that comets appear, fly off into space, and return; that above and around and below our solar system stretch the orbits of other worlds to illimitable distances; that our Sun, the centre of our system, has a diameter of 866,000 miles, is distant from the Earth 93,000,000 miles, and has a volume or bulk 1,300,000 times that of the Earth; that the planet nearest the Sun, Mercury, is 36,000,000 miles distant from it, and 57,000,000 miles distant from the Earth, and so on until we reach the planet Neptune which is 2,800,000,000 miles from the Sun and guards the outermost boundaries of our universe.

The Koreshan cosmogony, on the other hand, "maintains and demonstrates that the universe is a unit; it is an alchemico-organic structure, limited to the dimensions of 8,000 miles, diameter. According to the great law of analogy we hold that its form is cellular, that all life is generated in a cell--omne vivum ex ovo. The earth's shell, composed of metals and minerals, is about 100 miles in thickness, constituting a gigantic voltaic pile, the basis of the great galvano-magnetic battery, furnishing the negative

elements of the cell for the generation and supply of the sun's fuel. The concave surface of the earth alone is habitable. Superimposed upon the strata of the shell and emplaced in their static planes are the three atmospheres. At the centre we find the positive pole of the great battery--the central sun, around and with which the heavens revolve in twenty-four hours. All the energies of the physical universe are engendered through the relation of the positive centre to the negative circumference; a great complex battery of physical unity is thus attained and perpetuated." 1

This shell, one hundred miles in thickness, is composed of seven metallic, five mineral, and five geologic strata. The seven metallic layers or laminæ are "the seven notable metals," of which gold constitutes the outer rind of the shell. Beyond this is--nothing.

The inner surface of the shell is land and water, a concave expanse inhabited by every form of life. That we live on a concave surface, this cosmogony undertakes to prove by exactly the same phenomenon which "proves" the Earth's surface is convex--the disappearance of a ship "around" the world. Within the shell are the three atmospheres, of which the outermost, the atmosphere in which we exist, is composed chiefly of oxygen and nitrogen. The next or middle atmosphere is composed of pure hydrogen; and the one above of "aboran." Within this is the solar sphere, and within the whole and nucleus of all, the astral or stellar centre. Thus the starry nucleus is the centre of Space, and the metallic plates or laminæ the circumference

of Space. The heavens do not surround the Earth, but the Earth, the heavens.

In and occupying these atmospheres are not only the Sun and stars, but also "the reflections called the planets and the moon. The planets are mercurial disci moving by electro-magnetic impulse between the metallic laminæ or planes of the concave shell. They are seen through penetrable rays, ultra electro-magnetic, reflected or bent back in their impingement on the spheres of energy regularly graduated as the stories in the heavens." And, later on, they are further described as "little focal points of energy, partially materialized spheres in process of combustion. Their diameter is very small. Jupiter is nothing like the concept in the usual theory. The real planets are discs of mercury in the earth, between the metallic shells. They focalise the sun's energies in the atmosphere above us. They are what their names indicate--plan-ets--little planes." Of these mercurial discs there are seven.

Comets are not great streams of fiery matter; they are tiny things, broken up bits of crystalline energies spirating about the central solar sphere. "They do not fly off into space and return. They plunge into and feed the sun."

Neither is the Sun 886,000,000 miles in diameter, nor distant from the Earth 93,000,000 miles, since it is a body contained within the concave Earth. Given the Earth's diameter of 8,000 miles, the Sun's diameter would not be over 100 miles, or its distance from the concave habitable surface over 1000 miles. "The sun, moon, stars, including Sirius, Arcturus, Procyon, all the great nebulæ and comets, in short, all the things that exist in the heavens

Click to enlarge

PLATE XLV. CHART OF THE KORESHAN COSMOGONY

(From Cellular Cosmogony; Cyrus Reed Teed, 1898)

above, are contained in the shell. They are not worlds, or systems of worlds; they are not wanderers or erratic orbs, but points of generation of energy, every one of which has a distinctly different function belonging and necessary to universal perpetuation."

The revolution of the Sun and not the rotation of the

FIGURE 99. ''All things shew great through vapoures or myste.''

(From The Castle of Knowledge; Robert Recorde, 1556.)

[paragraph continues] Earth is the cause of day and night. Instead of appearing to rise above a convex surface, the Sun simply comes into our sphere of vision in the course of its revolution, and, at sunset, "goes out over the earth beyond the sea of hydrogen and arc of the heavens."

As to the Moon, which is an interesting part of this reversed cosmogony, it is to be first of all understood that there is uninterrupted reciprocal interchange of substance from centre to circumference of the shell; from the positive pole of the great battery--the central one,"

to the shell itself, described before as "a gigantic voltaic pile, the basis of the great galvano-magnetic battery, furnishing the negative elements of the cell for the generation and supply of the sun's fuel." For energy, it is explained, "is the destruction of matter as matter, and matter is the result of the destruction of energy as energy."

The origin of the Moon is in the Earth's shell, a sphere of energy derived from the planets and from the energies generated in the concave crust of the Earth. "The moon we see is projected or reflected from the great concave mirror, the metallic laminæ in the circumference; this moon is a sphere of force in the physical heavens, a sphere of crystalline energy upon which is implanted the picture of the earth's surface. The visible moon is a gravosphere or X-ray picture of the crust; hence we see light and dark places upon it, produced from the earth's surface and the geologic strata. The real moon is the laminæ of the earth's shell. The sun is the centre, the moon the circumference; the image or focalisation of each we see in the physical heavens. The moon does not shine borrowed light direct as in the Copernican system. But the sun and moon are two great lights; each shines with a light of its own, the light of the moon being derived from thousands of qualities of solar energies, after utilization, transmutation, and metamorphosis in the great shell."

The figures of Earth in this cosmogony are at first bewildering, until the eye becomes accustomed to the trick of "reverse." In the upper left-hand sphere (Plate XLV) we are looking at the "geography" of a concave surface--downwards as into a bowl. In the upper right-hand

spherical figure, we are looking at "the heavens in the Earth." The central spherical figure shows the three atmospheres which are the cause of day and night. It is a cross-sectional view of the "gigantic electro-magnetic battery with the sun as the perpetual pivot and pole." It is the southern hemisphere of the "cell." The smaller spheres show--upper left and right--the summer and winter solstices; lower left, the actual position of the Earth and its poles; lower right, the orbits of the planetary mercurial discs in the Earth's shell.

In this cosmogony, the Earth is not "supported"; it is suspended; it is dependent wholly upon its centre. It is eternal; it is the footstool of God and necessary to His Own existence; but it is All; "it is the ultimate and outermost limit of expression of the divine mind." Beyond its outer plate of shining gold there is nothing.

These are two of the three modern theories of the Earth as a hollow shell, differing widely from each other, but having as a common ground the habitability of the concave surface. The first conceives the Earth to be a body composed of at least five concentric spheres or shells, with enormous polar openings through which light and heat enter from the exterior Sun. The second affirms that the Earth is a single shell containing within itself the whole universe--the atmospheres, the planets, the heavens with the stars and Moon and Sun, and that on its concave surface man lives without ever knowing that he is enclosed within his world, like a bird in a cage. The third theory says that the Earth is a single shell, habitable on both its surfaces, with polar openings and an interior Sun.

This theory of the figure of the Earth was first published in 1913, in Marshall B. Gardner's A Journey to the Earth's Interior, or Have the Poles Really Been Discovered. Plate XLVI shows the exterior of his working model, and Fig. 100 is a diagram of the Earth bisected through its polar openings and showing the interior Sun.

According to these figures, the Earth's shell is a solid mass about 800 miles thick, with its own centre of gravity. Within as without there is land and water, their distribution inside being probably the reverse of the distribution without. That is, the Pacific and Atlantic ocean areas indicate great interior continents (perhaps the lost continents Atlantis-Lemuria-Pan-Mu!), and the space occupied by our continents are probably the places of the interior seas.

At each polar axis there is a great opening, about 1400 miles in diameter, around which both the exterior and interior waters, whose currents flow both ways, pour over "the lips of the world." Over this great curve, says Gardner, mariners might float, or flying men fly, with no more realisation--except for disturbances to their compass needles--that they were describing a half circle about a Titanic waterfall, than a voyager realises he is rounding the globe at any single stage--or total of stages--of a world-voyage. "They would only know that they had actually passed over the lip by the peculiar behavior of the magnetic needle and by the fact that they would see above them--as above them would mean toward the actual centre of the earth--the interior sun, which of course

Click to enlarge

PLATE. XLVI. The Earth according to Gardner, as it would appear if viewed

from space shorting the North Polar opening in the planet's interior. which is hollow and contains a central sun instead of an ocean of liquid lava.

(From A Journey to the Earth's Interior, Marshall B. Gardner, 1920)

would be shining whether the voyagers came under its influence during the day or during the arctic night."

No mariner has ever rounded this hypothetical lip, entered the great "concave," and emerged to tell his tale. But, says Gardner, messages from the Earth's interior have drifted and constantly do drift out to us by way of the contrary current. He cites log after log of North Polar expeditions, from the first to the last, all of them filled with curious contradictions and "unexplainable" phenomena; the "warm current flowing from the polar regions," the migrations northwards--instead of south--of birds and animals to feed and breed; the greater wealth of animal and vegetable life in the higher latitudes of the arctic regions than in the lower; the "red pollen of plants that grow--where?" scattered on icebergs and glaciers; the trees--some of them green-leaved--washed down in the warm polar current; the "case after case where the mammoth has floated out from the interior incased in glaciers and bergs and has been frozen in crevasses in the interior near the polar openings, and then carried over the lip by glacial movements into Siberia." From the noted evidence of fossil remains, complete coniferous trees, the presence of butterflies and bees, gnats and mosquitoes, incalculable shoals of fish, the musk-oxen and reindeer, the millions of birds--including the sandpiper, the "red snow," fresh-water ice, the recurrent appearances of "extinct" species--the mammoth, the mastodon, the mylodon, to say nothing of the remains of the rhinoceros, hippopotamus, lion, hyena, arid other tropical species all around the North Polar region, he concludes a common origin, beyond the

curve of the polar sea, after it has dipped below our horizon and has begun to flow, still north as we would say, yet south, into the Earth's interior.

The interior Sun which warms this inner Earth may be perhaps 600 miles in diameter. It is the central nucleus of the old nebular hypothesis; but, instead of throwing off a series of rings, each of which, breaking, formed a sphere and eventually a planet revolving around the central nucleus or Sun, the original nebula, says Gardner, "did not break up into a solar system, but condensed into one planet," this Earth. The spiral nebula is the first stage, he says, of a planetary body; the shell-like nebula with its central "star" or Sun is the second stage; the oblate spheroid with its central Sun and the two openings "which are always left when the nebula cools into a planet," is the third stage. One planet, that is, is like another. As, for instance, Mars and Earth.

The "ice caps" of Mars have accounted, until comparatively recently, for the clearly discernible bright spots at its poles. Of late astronomers have begun to doubt that Martian "ice" could send light-flashes across so many million miles of space. Gardner says that what we see is no more or less than the light from Mar's interior Sun, and that now and then, in observed brilliant points like stars flashing from the midst of the polar caps, we have caught the direct cosmic ray from Mars.

The Aurora Borealis is another unexplained phenomenon--those pulsating aerial fires of the north, which have their counterpart in the Aurora Australis at the South Pole. Gardner says that the scientists themselves know

Click to enlarge

FIGURE 100. Diagram showing the earth as a hollow sphere with its polar openings and central sun. The letters at top and bottom of diagram indicate the various steps of an imaginary journey through the planet's interior. At the point marked ''D'' we catch our first glimpse of the corona of the central sun; at the point marked ''E'' we see the central sun in its entirety.

(From A Journey to the Earth's Interior; Marshall B. Gardner, 1920.)

that the theory of their being the result of magnetic or electrical discharges does not explain them. The nearer the Pole, the more magnificent is the display--and he quotes Flammarion on them: "This light of the earth, the emission of which towards the poles is almost continuous . . ." It is just simply that, says Gardner, the light of the Earth; the light of its interior Sun, which pours through the lips of the Earth into the northern and southern skies. Nothing but interior storms of great violence, which choke the orifices for a time with dense clouds, can hold back the almost continuous stream of light. He quotes from Nansen's Farthest North in this connection. Nansen saw one night a marvelous Aurora. A brilliant corona circled the zenith with wreaths of streamers in several layers, all tending upward towards the corona which every now and then showed a dark patch in its centre towards which all the rays converged: "The halo kept smouldering and shifting just as if a gale in the upper atmosphere were playing a bellows to it." For a time it appeared as if the celestial storm abated; then the gale seemed to increase; it twisted the streamers into an inextricable tangle, until at last everything merged "into a chaos of shining mist." There are phrases in Nansen's description of this display which delight Gardner; "bellows," "gale," "storm." As a matter of intelligent explanation, he says, the light from the central Sun was being reflected from the higher reaches of the Earth's atmosphere, and the reflection was being interfered with by a violent storm in the interior of the Earth. Great clouds were in rapid process of formation and dissipation near the polar openings, so that at one moment the

rays of the central Sun shot clearly through, at the next moment they were blackened and hid.

Instead of departing for the interior of the Earth by way of Siberia, as Symmes begged to be aided to do, Gardner would pick up some Eskimos--whose ancestors, according to their own tradition, came from the "inside" where it is always light--some dogs and some sleds at God-haven, Greenland, and then proceed north along its coast to about 82° or 83°. What warm air, or warm water, the expedition would encounter would come from the north, and, if it were summer, mosquitoes would be the plague of plagues. From the coast of Grant Land or Peary Land, it would start on the last lap of the journey across the open polar sea. The Aurora Borealis would be no longer in the north, but directly overhead, and there would come a midnight perhaps that was strange day--their ship would be surrounded by an angry reddish light and a strange atmosphere. For the travellers would have passed far enough over the lips of the world to see, no longer the exterior Sun, but the inner Sun which never sets. It is no longer moving from east to west. It is stationary, or practically so, in "the centre of the world."

In that interior world, Gardner surmises, is the treasure house of all of the species of flora and fauna--and probably all of the races of man--that through millions of years have followed each other in endless procession over the exterior surface of the Earth; appearing, abiding for a while, and then passing away. Warned by great climatic changes on the outside, or by the tremors that precede great geological changes, they would have retreated, a few

of the "saved," to the hidden cities of refuge within the globe. So that here would be all of the myriad "missing links" in the disconnected story of the fractured outer Earth.

The return, incidentally, to the exterior would be no easier than the departure from it. For at each orifice the contrary waters endlessly struggle to pass, and it might very well be that the traveller caught in the wrong current would not be able to make the cross to the right one on which he could float easily out.

244:1 Cellular Cosmogony, Cyrus Reed Teed, 1905, p. 172.