Sacred Texts Legends and Sagas Celtic Index Previous Next

Buy this Book at Amazon.com

Scottish Fairy and Folk Tales, by George Douglas, [1901], at sacred-texts.com

THERE was a strange party assembled at the young farmer Gille Macdonald's that late spring evening, the night of the tryst at Inveraray, from attending which all and sundry were making their way home to the southwards.

Though a fine dry evening, it was a bit chilly; there was still a touch of winter in the season, and so no one was too proud or too robust to join the circle round the ingle, and warm themselves by the cheerful blaze.

There was a fisherman from Strathlachlan, a drover from Kilmun, two farmers from away south about Bute, a merchant from Rothesay, and a pedlar from anywhere you please, for he was always on the road from there to somewhere else.

Each had much to say for himself about his luck or otherwise at the tryst, and they were good company; but far and away the best of them all for conversation and news was the little pedlar, who sat on the three-legged stool in the centre, and had an answer ready for each and advice for all.

The conversation turned, as likely it would (for you see they had all been bargaining and selling), on how fortunes were made or lost, and one said this, and the other said that, each one seeming to have his own view of the matter, and deeming his own way the best; but what the little pedlar remarked just before they broke up for the evening was the only thing that Gille Macdonald remembered or thought worth listening to.

For the pedlar had said in answer to how would he set to work to make his fortune, that, if he was a bit bigger, and was a younger and stronger man, he knew a place where a fortune could be got for the digging, only it needed a stouter heart and a more adventurous spirit than he possessed to attempt the search. So he for one would still stick to his pack.

After the cup had passed round for the last time, and all were moving off to the beds provided for them, Gille Macdonald gently touched the sleeve of the pedlar, and asked him if he would kindly wait a

Click to enlarge

Gille Macdonald drew the little pedlar towards the ingle, and filling his glass once more begged him to be seated.--Page 245.

Scottish Fairy Tales.

moment after the others had gone, as he wanted to ask him privately a certain question.

The pedlar was delighted to oblige so kind a host as Gille Macdonald, and said he certainly would.

So when the kitchen was clear of company, Gille Macdonald drew the little pedlar towards the ingle, and filling his glass once more, begged him to be seated, and if it so pleased him, to say what he meant by the place where a fortune was to be had for the digging, if only a brave heart and a stout spirit were there to attempt the deed.

"Oh!" replied the little pedlar, "that is it, is it? Well, the place I mean is over on the west side of Kintyre, a day's journey from here on horseback. Across the loch and by the road over the ridge from Tarbert, there is the castle of Taychronan, inhabited by an evil old gentleman who is reputed to be eminently rich; and that that is not a mere rumour I myself know, for he has a treasure buried in the well in the garden. With these two eyes I saw him shovelling in ducats and gold pieces just as if they were potatoes, only a month ago. I would have liked much to have secured some of them, but you know what a fragile little fellow I am, and I was too much afraid of the old gentleman to do anything of the kind.

"Now, don't let me induce you to go after the treasure; you are comfortably off, and can want nothing more than what you have got already. I should be sorry if you fell into the old gentleman's clutches, for evil things are spoken of him, and he is said to be

not only a selfish old miser, but a powerful magician, and a cruel as well. Now, good night," and the pedlar walked off to his couch.

In the morning the whole party of the night before left the farm, thanking their host, and going their several ways. As to the pedlar, he had started at cock-crow, to be early on the road, so Gille Macdonald had no further chance to question him about the castle and the treasure, of which he had dreamed all night, waking up in the morning quite determined to investigate, and, if possible, secure it.

So he occupied himself that day in putting his farm in order, and gave instructions to his head servant that this and that should be done in his absence, and this and that should be done if he never came back at all; and this preparation finished, the very next morning he saddled his grey mare and took the road that led to the nearest ferry on Loch Fyne side.

The crossing was accomplished successfully, for it was fine weather for the time of the year, while a light breeze and sunny sky put him in good spirits for his adventure.

A fair was being held at Tarbert when he arrived there; booths were erected up and down the streets, and music and dancing were going on by the shore. There also many people were gathered together from the surrounding country, with mountebanks and singers and such like turning an honest penny among the crowd.

One little chap in especial Gille Macdonald could not help observing with interest, for he would throw

three or four somersaults on the hard pavement without stopping--yes, and could throw them backwards and forwards at pleasure for what trifle the spectators might fling him in his upturned hat after each performance.

WOULD THROW THREE OR FOUR SOMERSAULTS.

Amongst others the mannikin approached Gille as well.

"Well, then, a copper you must be satisfied with, small friend," said Gille Macdonald; "I can't give you more, for we are both seeking a fortune, I see, in our different ways."

"How so, friend?" said the mannikin. "Where and how do you seek a fortune?"

"With a strong arm and a stout heart," said Gille Macdonald. "I hope to get a fortune by digging;" and he passed up the street.

"Stay," said the mannikin, running after him; "where did you say a fortune was to be got for the digging?"

Well, Gille Macdonald did not like to be interrogated further, and in fact he was angry with himself for having been led to speak of his adventure at all; but he did not wish to seem rude to a poor little mite, so he said, "Oh, not far away; over the hills to the west. Good night."

"Good night," said the dwarf; and Gille Macdonald thought there was a queer tone in the way it was muttered, and somehow he did not like it at all; but everything was soon forgotten in the enjoyment of good company at the inn, where, the host being an old friend of his, he put up for the night.

Early next morning he was astir, and saddled his mare, giving her a good feed, for she had a long journey before her, and he wished to reach Castle Taychronan before nightfall, so that he might be able to have a look round unknown to the old man, and to find out where the well was situated.

As he journeyed on his thoughts naturally turned to the adventure before him, and in a brown study he let the mare jog along as she chose, taking no heed of anything till, with a start, he was aroused by a squeaky little voice beside him, which struck him as strangely familiar. Looking down, he was aware of a little man walking by his side, with a face exactly

like the mannikin's he had seen at the fair the day before.

Yet it could not be the same, for that one was so very small and humpbacked, while this, though a wee bit creature, was not anything out of the run of little men. Yet he had the same hunch on his back, the same long pointed red nose and queer squint as had his acquaintance of the fair-yes, and his very voice too, only louder and stronger.

"Well met," quoth the little man.

"Well met," said Gille Macdonald.

"We are fellow-travellers, I see," said the wee man.

"For the present, yes," said Gille Macdonald, and he urged his mare on along the road.

"We'll meet again, maybe, before long," cried the wee man after him.

Now it made Gille Macdonald laugh to think such a crippled creature would ever catch him up again; but something about the dwarf he did not like, and he was not comfortable till he had galloped on a mile, and had lost sight of him.

It was about noon, and Gille Macdonald was giving his mare a quiet walk down that part of the highroad which, having kept to the upper moorland for some miles, here makes a rapid descent towards the sea again at Ronachan Bay. What was his astonishment to hear again the now familiar voice calling to him from the other side of the dyke, and before he regained his composure he saw the old, ugly face peering at him from behind a stunted willow, whose

twisted roots crept in and out like snakes among the stonework.

"Well met," quoth the creature; and this time that which accosted him was a full-grown man just about his own size, and Gille Macdonald was not a small man by any means.

A LITTLE MAN WALKING BY HIS SIDE.

Gille Macdonald could not believe his eyes. There was the long red nose, and the squinting eyes, and the round bumpy back, but six foot the creature was if an inch. It could not be the same; but that it had some uncanny connections With the mannikin he met at Tarbert, and again already that morning, he felt certain.

You may be sure he liked the meeting less than ever; even his docile old mare shied on one side as the thing now stepped into the middle of the road. But Gille Macdonald thought civility could do no harm, so he gave him good-day as before.

"We are fellow-travellers, I see," said the thing, and he squinted horribly with his ugly eyes.

"For the present, yes," said Gille Macdonald; "but I must be jogging on," and he struck spurs into the mare.

"We'll meet again, maybe, before long," said the man.

It did not need much to make the mare go along the road at a good rate, and not for a while did Gille Macdonald feel the eerie thrill leave him; but young spirits are not easily upset for long, so before an hour had passed he was singing as blithely as before.

It's a long, straight bit of road from Ballochroy to Tayinloan, as every one knows who has made the journey, and at evening, just as Gille Macdonald chanced to be entering upon it, the sun was at his back, and he could see a long way down before him, with everything standing out very clearly.

"What a funny thing," said he, "for people to have planted a tree there right in the middle of the road!" for a little bit ahead there was what seemed to him a young fir-tree sticking up straight before him. "They do odd things in this part of the country, surely." But you may imagine what his astonishment was when he saw the thing move along in the direction in which he was going. He rubbed his eyes,

and thought it must be some trick of light and shade. It couldn't be a human being!--yes, it was! and then the strange things he had seen that day flashed upon his mind, and he felt sure this was again another of the same nasty crew he had so wished to avoid.

"I shall most decidedly turn back," said he, and he was giving the rein a pull to one side when the gaunt figure in front turned round, and, stepping to one side, took off its hat with a low bow, and with the same voice as he had heard before said--

"Well met."

"Well met," said Gille Macdonald, shivering all over.

"Pray pass on," said the tall man; "we are fellow-travellers, I see"; and he rolled his squint eyes and shook his long red nose in a fearsome manner.

"For the present, yes," faltered Gille Macdonald. "But, excuse me; I must be pressing on," and he urged his steed past the creature, for now it was just as bad to go backward as forward.

"We'll meet again, maybe," cried the tall man after him, as Gille Macdonald sped along the straight road; for both man and beast were thoroughly frightened by this time, and they wanted to put as much country between themselves and that ugsome thing as they could.

Gille Macdonald did not forget the apparition this time, or his saying they would maybe meet again. At every turn he expected something terrible to appear; under every rock he thought he saw some horrid shape lurking, and ready to pounce. The evening

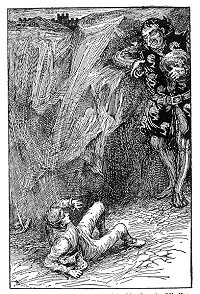

Click to enlarge

"Well met," said from somewhere above him, the voice Gille Macdonald knew too well.--Page 258.

Scottish Fairy Tales.

also became dark and lowering, which added to his fears. The sun had set, and a fitful moonlight, now bright, now dark, made everything look larger and grimmer than it would appear by day. The trees by the roadside took fantastic shapes, and seemed to stretch out their arms fiercely over the path, with eager claws ready to seize him; in every sigh of the wind he heard again the croaky, familiar voice; in every echo of his mare's hoofs a weird footfall rang behind him.

Suddenly he came to a spot where the road seemingly had no outlet--rocks on this side, rocks on that, "Yet there must be some way through," thought he, "or the road would not lead this way," and he urged his horse forward into the darkness. A plunge! His faithful steed reared high in air, and, throwing his master, coursed back down the road, screaming with fear.

"Well met," said from somewhere above him the voice Gille Macdonald knew too well; and as he lay bruised on the road, he saw in the moonlight a gigantic figure blocking up the whole pass between the two steep rocks through which the road stretched beyond.

"Well met," again said the voice. "But you don't seem to have a civil answer for me as before;" for Gille Macdonald was so terrified his tongue stuck in his jaws, and he could not reply. "I said maybe we would meet again, and, by my troth, the pleasure seems to be all on my side."

"With your permission," said Gille Macdonald,

gasping for breath, "I will now go and see if I can find my horse."

"With my permission you shall do nothing of the sort," replied the figure. "You have come a long way to see my castle, and within it you shall rest this night. Ay, and for many a night to come, for the matter of that."

"Your castle?" said Gille Macdonald. "What do you mean by that?"

"Where gold can be got for the digging: is it not so?" said the voice. "Come, you thief, you hypocrite, you wretched slave! know I am the magician, and Castle Taychronan is my home. There you shall have the digging you looked for, as my slave during your lifetime, with the digging of your own grave at the end of it."

Poor Gille Macdonald had not a word to say, so the giant--for he was a giant indeed of twenty feet by this time--took him up from the road and carried him by his waistbelt to the castle, which was a couple of miles off. Yet the journey only occupied but little time, for the giant's strides were long, and he was in a hurry to get home.

When they arrived at the castle gate he set Gille Macdonald down on the ground, and, putting his head down, he said a queer word below the lintel, and immediately, from being a giant over twenty feet high, he dwindled to the size of a man of seven feet or thereabouts, after which transformation he turned round and drove Gille Macdonald into the castle before him with a cudgel,

They entered now a large and lofty hall, roofed with black oak, dark and grim with smoke and age. There was spread some supper on an oaken board, huge and vast, fit for a giant; while on an open hearth blazed a great fire of pine logs, which lit the ball with a fitful gleam. In its ruddy light Gille Macdonald observed that the only furniture, besides the table and a huge couch in the corner, was five oaken presses set along the wall, all with panels carved in quaint devices, and hinges and locks of burnished brass.

"Serve my dinner," said the giant; "and be quick about it."

Gille Macdonald did so without any demur. He was getting his wits together as best he could, so he did his best to please in the meantime, meditating the while on his unfortunate fate, and wondering whether there was any chance of escape. An idea soon came into his head, and while handing a beaker of wine to the giant, he got up in a chair behind him, and held it for some moments right over his head.

"What are you doing? what are you up to?" said the giant. "What the mischief makes you hold it up there in that way?"

"Oh, I beg your pardon, I'm sure," explained Gille Macdonald; "you see I'm so accustomed--"

"Accustomed to what?" asked the giant sharply.

"To hand the cup to my master at home in this way; he likes me to hold it as near his mouth as he can."

"But that's ridiculously high," said the giant.

"Not a bit of it," explained Gille Macdonald; you are not the only giant in the kingdom." "Oh, ah!" said the giant, a bit taken by surprise.

Then, recovering himself, he said, "He must be a

"WHAT ARE YOU DOING?" SAID THE GIANT.

queer creature; but see you, I won't have any of your silly tricks here; so behave."

"You won't be troubled with them very long," said Gille.

"What d'ye mean by that?" said the giant.

"Only that my master will soon be here to take me away."

"Take you away when you are in my house! I'd like to see any one do that," remarked the giant with a snort.

"So should I," said Gille Macdonald; "and he will, too."

The giant got up with a bounce and went to the fire, where for a space he stood buried in thought. Meanwhile Gille Macdonald did not see any reason why he should not have a bit of the pasty and a sup of the wine; but he did not get long to do it, for the giant, turning round, said, as if to relieve his mind, "Well, he can't find you here, for he don't know where to look for you."

"Your attention, Sir, for a moment," said Gille Macdonald. "Do you see these brogues of mine? well, look at the heels; they are shod with brass. All my master's servants, men, women, and cattle, are shod with shoes of this description, so wherever they go, there he can trace them to the world's end."

"What sort of person do you say your master is? said the giant, feigning composure.

"Oh! I can't be bothered to explain," said Gille Macdonald, plucking up his spirits as he saw the giant was losing his. "You'll see for yourself presently; he'll be here before to-morrow evening, most likely, and not in the best humour, either."

At this the giant got still more subdued, and said, "Oh! it does not matter, of course, to me whether

your master comes or not; but just tell me, is he as big a man as I was when we met in the pass? I'm not curious, but I only want to know."

"Is that the very biggest you can make yourself?" said Gille Macdonald, not to be taken off his guard.

"Yes," said the giant, "it is, and bigger than what you've been accustomed to."

At this Gille Macdonald burst out laughing.

"You'll excuse me," said he, "but you'll be like a baby beside him, if that's all you can do."

At this the giant, in a great state of trepidation, again strode to the fireplace, and kicked the blazing logs about from one side of the hearth to the other in a most vicious manner, just to hide the fright he was now in.

"I think you had better be off at once," said he.

"I wish I had never seen your ugly face."

"That's not very civil," said Gille Macdonald, "especially as you were so very anxious for my acquaintance on the road here."

"Get out of the place this minute!" roared the giant. "Here's a piece to drink my health with, if you will only be quiet, and go."

Gille Macdonald took the piece and made for the door; but he was only pretending, for he saw now the giant was completely cowed, and he had no intention of leaving the castle without some treasure after all his troubles; so he turned round, just as he was leaving the hall, and said, "It is really very good of you to give me this piece, and to send me home; it is more than I would have expected, so I think it is

only civil to tell you that whether I go or stay my master will come here after me, as once on the trail of the brazen brogues he never leaves it, so you had better be prepared. Hush! there, don't you hear that?" as a gust of wind swept round the tower;

"YOU'LL BE LIKE A BABY BESIDE HIM."

[paragraph continues] "there he is blowing his nose! Oh! don't alarm yourself; he is miles and miles off still."

"Come in and sit down," said the giant, "and I will make it worth your while to tell me how I can escape the notice of your master; for he seems to be an irascible kind of fellow, and I should not like a

quarrel to take place with any friend of yours in my own house."

"Well," said Gille Macdonald, "just you hide till he has come and gone. But stay, I don't see how you are to do that; you're so very big."

"I'll get into that corner by the door," said the giant

"Get into that corner?" cried Gille Macdonald.

"How can you with your size, indeed?"

"How can I?" roared the giant. "I'd have you to know there is no can or cannot in this house for me;" and he went behind the door and said a very queer word, and there the giant was about five feet high instantly, just the right size for the hiding-place.

"Oh," said Gille Macdonald, "that won't do at all; my master--will be poking about all over the place. That's the worst of him, he is so curious, and will be certain to find you out."

"Rot his curiosity!" said the giant. "Then under the table will do," and he put his head under the table and said a very, very queer word, and in an instant there he was, just small enough to stand under the table.

"That's better," said Gille Macdonald, and he walked to the end of the hall. "But no; I can see you easily from here, and my master has such plaguy sharp eyes."

"Plaguy sharp eyes! Plague take them and you too! I wont diminish another inch to please anybody."

"Hush, hush!" said Gille Macdonald, as a louder gust of wind whirled round the castle; "there he is, still a good mile off; but coming fast, and oh! what a cold he's got in his nose! Just make the best of it. But don't blame me if he wrings your neck."

Then the giant rushed out from under the table and said a very, very, very queer word under the footstool, and there he was, sure enough, six inches high, a tiny mannikin squinting at Gille Macdonald from between its two legs.

"I really think be cannot see you there," said Gille Macdonald, "though he is most inquisitive, and does kick things about; so let's see, to make quite sure," and saying this, he gave the footstool a kick with his foot. "No, it won't do; I saw you then quite clearly when the stool moved. Can't you get under something smaller?"

"No, not for you or for your vile master," squeaked the mannikin. "I won't, I won't, I won't!"

"Then take the consequences! There he is at the door," as a fierce gust of wind roared down the chimney. "His nose will be as red as yours if he goes on blowing it at that rate."

Without a word the mannikin crawled out from under the footstool, and scrambling to the hearth, he said a very, very, very, very queer word under the hearthstone, and there he was in a moment, as small as a black beetle.

"Where have you got to?" said Gille Macdonald.

"Under the hearthstone," chirruped the mannikin.

"Nonsense; I can see you still under the footstool," replied Gille Macdonald.

"You can't," said the mannikin. "I'm under the hearthstone."

"Don't tell me lies!" said Gille Macdonald, "or I'll tell my master."

"Then will this satisfy you?" squeaked the mannikin, and a little, ugly black beetle crawled out from under the hearthstone. "Do you see me now? Are you satisfied now?" said he.

"I'm perfectly satisfied," said Gille Macdonald, and he put his foot on the beetle, and squish, sqrunch! there was nothing but a black patch seen on the floor.

"Well, that's over," and Gille Macdonald sank with a sigh of relief into the giant's chair.

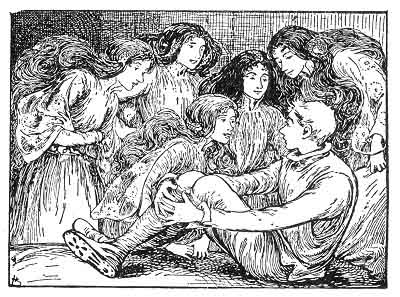

But with a bang all the five doors of the five presses opened, and before he could say with your leave or by your leave, Gille Macdonald found himself surrounded by five maidens in seagreen-coloured attire, who clasped him round the neck and arms, kissing, tickling, and nearly throttling him, all the time laughing and giggling like wild lunatics.

"Have done! be off! Away with you, saucy wenches! Get off, I say!" choked Gille Macdonald, struggling to be free; but the more he pushed and kicked the closer they hung round about him and embraced him. What would have been the end of it I don't know, if he had not, with a violent effort, got clear, and, flying to the corner of the hall, he stood at bay with the giant's footstool held out before him in defence,

Click to enlarge

"Have done! be off! Away with you! Get off, I say!" choked Gille Macdonald, as the maidens hung round about him and embraced him.

Page 262. Scottish Fairy Tales.

"Keep your distance," cried he. "I'll give the first one who comes within a foot of me a nasty smack, I vow I will!" and he whirled the footstool round and round in a circle in front of him.

And there were the five maidens dancing, laughing, kissing their hands to him, and kicking up their legs in a manner he had never seen before.

"Come out of the corner, you coward you!" cried they. "You call yourself a man, and go on in that way? Bah! ugh!" And oh! what faces they made when they said "Ugh!"

"I'll not come out or put the stool down," said Gille Macdonald, "till you promise to behave--that's flat. What is your business? tell me, go about it, and let me go about mine."

"That's just where it is; your business is ours," said they, "and whatever you have to go about, we must go about too. You've got to marry us all, so it is no use fretting about what must be."

"What can't be, you mean," said he. "All of you, did you say? What's the meaning of that? and don't all speak at once," for they began screeching and screaming together in return.

"Well," said the eldest, "look here. Now can we or you help it? We are the King of Loch Lin's daughters, and we have been locked up in those cupboards for three mortal years, because we vowed we would not marry that giant; and we must marry you, because we also vowed that whoever let us out should be our husband. You would not have us forswear ourselves, would you?"

"Well, if that's the case," said Gille Macdonald, "sit down quietly at that table, and we'll talk over the matter seriously; but mind, any misbehaviour, and I will bang each of you over the head."

So they promised to sit quietly at the table if he came out and sat at the end.

So they did, and so he did; but he kept the stool at easy reach of his hand, all the same.

After a great deal of arguing he explained that it was quite impossible for him to marry them all, but that they must choose which of the five should represent the others, and then he would see if anything could be done.

Then it was decided that the green maidens should play for a husband, and whoever won should be his wife. So they took the giant's dambrod from the top of the chimney-piece, and for two hours did they play; but such was the cheating and contriving that none won and none lost. So they said it was evident that he must marry them all.

"No," said Gille Macdonald; "this is ridiculous, and, what is more, it's getting late, and will be next morning very soon. Try each of you a cast of the dice, and we will see if it can be managed that way, perhaps."

So they took the bones and boxes from above the chimney, and threw for a husband; but they all cheated so and contrived so, that none won and none lost. So they said now he must marry them all, whatever he said or thought.

"No," said he, "I won't; but do get me some

supper, I'm so famished, and then I'll tell you how we will settle it."

So they got his supper, and sat down, waiting, round the giant's table.

"This is the trial," said Gille Macdonald, when he had finished and collected his thoughts a bit. "Tomorrow I will ask you what colour I would my future bride should be dressed in, and whoever names the colour to my taste she shall be my wife. You can't cheat or contrive about that, I fancy."

"Very well," said the green maidens; but the youngest put a draught in Gille Macdonald's cup, when he was not looking, a potion that would make him dream--yes, and speak in his dream too. "Surely now he will tell us the secrets of his mind," said she.

After draining the cup, Gille Macdonald went and lay down before the fire on the giant's couch, and the green maidens made as if they were going upstairs, after giving him good-night; but as soon as he was fast asleep, they crept back into the room, and hid themselves about the room, waiting for what would come to pass.

Sure enough, very soon the draught began to take effect, and he dreamed of his farm and the hillsides of Strachur, speaking out aloud in his dreaming--

Yellow is the corn in the glen of Ardkinglas;

And yellow is the bracken on the sides of Ben Ima;

Yellow is the hair of my loved one,

And yellow shall be the dye for her kirtle."

Then the green maidens arose, and with a low laugh they left the hall.

The next morning the sun shone through the window and woke Gille Macdonald, but not before the green maidens had come. down and prepared the breakfast; for they were so pleased at their liberty, their cheats, and contrivances, that whether the sun

"PUT YOUR QUESTION," THEY SAID.

intended to get up or not, they did, and indeed, I don't think they closed an eye all night.

"Put your question," said the green maidens, when they perceived he was awake.

And Gille Macdonald put the question concerning the colour of his bride's robes to each in turn, and they all answered, "Yellow."

At this Gille Macdonald was so taken aback it was no use his saying they had not guessed right, for his looks said so.

"There now," said they; "you see there is no help for it; you must marry us all."

"Now, really," said Gille Macdonald, "in such a serious business you must give me another chance. But once more I will try you, and if that does not succeed, well, we'll see about it."

So the green maidens said they would have one more trial, and that in all conscience must be the very last; and they laughed together, for they felt quite confident of the result, and as they looked upon Gille Macdonald as a sort of fool to be easily taken in.

"Well, listen," said he; "whoever can tell me what favour it was the cod-fish of Ardminish asked of the widow woman of Gigha, that one I shall marry."

Then they said, "We must go out into the garden and think about the answer for a moment,"

"Do so," said Gille Macdonald, "and I will give you five hours for consideration."

So off they went; but, bless you, he knew perfectly well they had gone off to the Loch to see if the cod-fish would tell them for a consideration what favour he asked of the widow woman.

"Now is my chance," quoth Gille Macdonald, and he went without loss of time to the well in the garden, where he found, sure enough, the treasure the old pedlar had told him about. Having filled his wallet, without good-day or with your leave or by your leave

to anything or anybody, he went straight out of the door and took the road home.

"Oh, if I could only find my dear old grey mare," he sighed, "how pleased I should be! Ah, then I should feel safe from these bold wenches."

Scarcely were the words out of his mouth, when, turning a corner, he saw his old grey mare grazing by the roadside, and at his call she came whinnying up to him; and I can't say which of the two was the gladder to meet with the other.

On her back he vaulted, and away towards Tarbert they galloped. His heart was as light as his wallet was full; and the mare's head being turned homewards, both were in a hurry, so there was no need for whip or spur. Nor did he wait at Tarbert that evening, but for a large sum (what was money to him now?) begot the ferryman to take him across there and then; and by midnight he was at his own hearthside, with his mare in her cosy stable.

Next morning he was out and about with his servants, so eager was he to begin improving his farm with his new wealth, and he worked, and kept his gillies working, till the evening star came and winked at the sun setting over Ben Dearg.

Then it was that, as he rested, leaning over the gate at the end of the field, he thought he heard voices up the road, and looking along there, what should he see about a mile off but five figures in green coming towards him, dancing, gesticulating, and chattering in a most unusual manner! No need, too, for him to ponder what visitors these might

be, or what their errand was; so calling to his oldest and ugliest hind, he bade him cover himself with his plaid, and sit down by the hearth with a porridge bowl in his hands, just as if he were supping brose. Then running to the stable, he cut off a foot of his grey mare's tail, which he plaited over the forehead of the hind, letting it fall in grizzly ringlets over his nose.

"Now mind," said he, "to any visitors who chance to come, say you are the goodwife of the house, and ask them their business. As for myself, I will hide behind the peat-stack yonder, and bide the issue."

In less time than I write this, there was a rare tapping at the door, and as the hind bid them enter the five green maidens hurried into the house.

"Is the goodman at home?" said the five green maidens, all at once.

"No; but I'm the goodwife, and may I ask you what is your business?"

At this answer the five green maidens stood for a moment transfixed with rage and wonder, then, shrieking aloud, they gathered up their coats and fled helter-skelter from the house down the road to the loch, and were seen no more.

So Gille Macdonald lived ever afterwards a life of wealth and comfort; and if he is not married yet, he can't say it is for the want of offers, can he?