Sacred Texts Legendary Creatures Symbolism Index Previous Next

Buy this Book at Amazon.com

Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art, by John Vinycomb, [1909], at sacred-texts.com

"The most remarkable remembrance," says Dean, "of the power of the paradisaical serpent is displayed in the position which he retains in Tartarus. A cuno-draconictic cerberus guards the gates; serpents are coiled upon the chariot wheels of Proserpine; serpents pave the abyss of torment; and even serpents constitute the caduceus of Mercury, the talisman which he holds in his hand when he conveys the soul to Tartarus. The image of the serpent is stamped upon every mythological fable connected with the realms of Pluto. is it not probable that in the universal symbol of heathen idolatry we recognise the universal object of primitive worship, the serpent of paradise?"

"Speaking of the names of the snake tribe in the great languages," Ruskin says, "in Greek, Ophis meant the seeing creature, especially one that sees all round it; and Drakon, one that looks well into a thing or person. In Latin, Anguis, was the strangler; Serpens, the winding creature; Coluber, the coiling animal. In our own Saxon the Snake meant the crawling creature; and Adder denoted the groveller."

The true serpents comprise the genera without a sternum or breastbone, in which there is no vestige of shoulder, but where the ribs surround a great part of the circumference of the trunk. To the venomous kind belong the rattlesnake, cobra de capello, spectacled or hooded snake, viper, &c. So the non-venomous, the boa constrictor, anaconda, python, black snake, common snake.

The minute viper, V. Brashyura, is celebrated for the intensity of its poison, and is truly one of the most terrible of its genus. The asp of Egypt, or Cleopatra's asp (Coluber naja, Lin.), was held in great veneration by the Egyptians; and it is this snake which the jugglers, by pressing on the nape of the neck with the finger, throw into a kind of catalepsy, which renders it stiff, or, as they term it, turns it into a rod.

All snakes, says the celebrated naturalist Waterton, take a motion from left to right or vice versa—but never up and down—the whole extent of the body being in contact with the ground, saving the head, which is somewhat elevated. This is equally observable

both on land and in water. Thus, when we see a snake represented in an up-and-down attitude, we know at once that the artist is to blame.

Another misconception exploded by Waterton is the common and accepted notion that a snake can fascinate to their destruction and render powerless by a dead set of its eye the creatures it makes its prey. Snakes have no such power. The eyes, which are very beautiful, do not move, and they have no eyelids; they have been placed by nature under a scale similar in composition to the scales of the body, and when the snake casts it slough, this scale comes away with it, and is replaced by a new one on a new skin.

Noli me tangere—do not touch me with intent to harm me—is, continues Waterton, a most suitable motto for a snake, which towards man never acts on the offensive (except perhaps only the larger species which may be in waiting for a meal, when any creature, from a bull to a mouse, may be acceptable). But when roused into action by the fear of sudden danger, ’tis then that, in self-defence a snake will punish the intruder by a prick (not a laceration) from the poison-fang, fatal or not, according to its size and virulence.

A writer in the Daily Telegraph of July 23, 1883, giving an account of the new reptile house in the Zoological Gardens, Regent's Park, dwells upon the surpassing beauty of a python that had just cast its skin, a very miracle of reptilian loveliness. Watch it breathing; it is as gentle as a child, and the

beautiful lamia head rests like a crowning jewel upon the softly heaving coils. Let danger threaten, however, and lightning is hardly quicker than the dart of those vengeful convolutions. The gleaming length rustles proudly into menace, and instead of the voluptuous lazy thing of a moment ago, the python, with all its terrors complete, erects itself defiantly, thrilling, so it seems, with eager passion in every scale, and measuring in the air, with threatening head, the circle within which is death. Once let those recurved fangs strike home, and there is no poison in them, all hope is gone to the victim. Coil after coil is rapidly thrown round the struggling object, and then with slow but relentless pressure life is throttled out of every limb. No wonder that the world has always held the serpent in awe, and that nations should have worshipped, and still worship, this emblem of destruction and death. It is fate itself, swift as disaster, deliberate as retribution, incomprehensible as destiny." It would be tedious to recapitulate the multitude of myths through which the "dire worm" has come to our times, dignified and made awful by the honours and fears of the past. A volume could hardly exhaust the snake-lore scattered up and down in the pages of history and fable.

"The python in the Zoological Gardens, however," adds the same writer, "though it may stand as the modern reality of the old-world fable of a gigantic snake that challenged the strength of the gods to overcome it, presents to us only one side of snake

nature. It possesses a surprising beauty and prodigious strength; but it is not venomous. Probably the more subtle and fearful apprehensions of men originated really from the smaller and deadlier kinds, and were then by superstition, poetry and heraldry extended to the larger. The little basilisk, crowned king of the vipers; the horned 'cerastes dire,' a few inches in length; the tiny aspic, fatal as lightning and as swift; and the fabled cockatrice, that a man might hold in his hand, first made the serpent legend terrible; their venom was afterwards transferred, and not unnaturally, to the larger species. It was the small minute worms, that carried in their fangs such rapid and ruthless death, which first struck fear into the minds of the ancients, and invested the snake with the mysterious and horrid attributes whereunto antiquity from China to Egypt hastened to pay honours."

Cadmus and his wife Harmonia were by Zeus converted into serpents and removed to Elysium. Æsculapius, son of Apollo, god of medicine, assumed the form of a serpent when he appeared at Rome during a pestilence; therefore he is always represented with his staff entwined with a serpent, symbol of healing. Similarly represented was Hippocrates, a famous physician of Cos; who delivered Athens from a dreadful pestilence, in the beginning of the Peloponnesian War, and was publicly rewarded with a golden crown, and the privileges of a citizen. Therefore it is that the goddess of health bears in her hand a serpent.

The caduceus of Mercury was a rod adorned with wings, having a male and female serpent twisted about it, each kissing the other. With this in his hands, it was said, the herald of the Gods could give sleep to whomsoever he chose; wherefore Milton, in "Paradise Lost," styles it "his opiate rod."

Jupiter Ammon appeared to Olympias in the form of a serpent, and became the father of Alexander the Great:

Jupiter Capitolinus in a similar form became the father of Scipio Africanus.

In the temple of Athena at Athens, a serpent was kept in a cage and called "The Guardian Spirit of the Temple." This serpent was supposed to be animated by the soul of Ericthonius. It was thus employed by the Greeks and Romans to symbolise a guardian spirit, and not unfrequently the figure of a serpent was depicted on their altars.

Upon the shields of Greek warriors, on ancient vases, &c., the serpent is often to be seen blazoned.

The serpent monster Python, produced from the mud left on the earth after the deluge of Deucalion,

|

The serpent in Christian Art figures in Paradise as the tempter of Eve under that form, and is generally placed under the feet of the Virgin, in allusion to the promise made to Eve after the Fall: "The seed of the woman shall bruise the serpent's head." The heart of the serpent being close to the head, renders a severe "bruise" there fatal. The serpent bruised the "heel" of man—i.e., being a cause of stumbling, it hurt the foot which tripped against it (Gen. iii. 15).

The brazen serpent erected by Moses in the wilderness, which gave newness of life to

|

admit the propriety when he compared himself to the healing serpent in the wilderness.

The serpent is placed under the feet of St. Cecilia, St. Euphemia, and many other saints, either because they trampled on Satan, or because they miraculously cleared some country of such reptiles. St. Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland, is always represented habited as a bishop, his foot upon a viper, the head transfixed with the lower extremity of his pastoral staff, from his having banished snakes and all venomous reptiles from the soil of Ireland. As the symbol of the evil principle, a diminutive specimen of the dragon, guivre, or winged snake was more frequently used, wriggling under foot.

The serpent is emblematical of The Fall; Satan is called the great serpent (Rev. xii. 9); of Wisdom: "Be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves" (Matt. x. 16); of Subtlety: "Now the serpent was more subtil than any beast of the field" (Gen. iii. 1); of Eternity: a serpent in a circle with its tail in its mouth is the well understood symbol of unending time.

The serpent figures largely in Byzantine Art as the instrument of the Fall, and one type of the Redemption. The cross planted on the serpent is found sculptured on Mount Athos; and the cross surrounded by the so-called runic knot is only a Scandinavian version of the original Byzantine image—the crushed snake curling round the stem of the avenging cross. The cross, with two scrolls at the

foot of it typifying the snake, is another of its modifications, and a very common Byzantine ornament. The ordinary northern crosses, so conspicuous for their interlaced ornaments and grotesque monsters, appear to be purely modifications of this idea." *

Boniface, the Anglo-Saxon missionary, in his letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury, inveighs against the luxuries of dress, and declares against those garments that are adorned with very broad studs and images of worms, announcing the coming of Antichrist.

In the wonderfully intricate interlacing of snakelike and draconic forms of celtic art which appear in the marvellously illuminated manuscripts executed in Ireland of the sixth and seventh centuries, the great sculptured crosses, as well as in gold and metal work, are seen unmistakable traces of the traditional ideas relating to the early serpent-worship.

"The serpent," says Mr. Planché, "the most terrible of all reptiles, is of rare occurrence in English heraldry. Under its Italian name of Bisse it occurs in the Roll of Edward III.'s time, 'Monsire William Mal bis d’argent, a une chevron de gules, a trois testes de bys rases gules' (Anglicé; argent, a chevron between three serpents’ heads erased gules)."

The well-known historic device, the Biscia or serpent devouring a child, of the dukedom of Milan

is of much interest. There are many stories as to the origin of this singular bearing. Some writers assign it to Otho Visconti, who led a body of Milanese in the train of Peter the Hermit, and at the crusades fought and killed in single combat the Saracen giant Volux, upon whose helmet was this device, which Otho afterwards assumed as his own. Such is the version adopted by Tasso, who enumerates Otho among the Christian warriors:

From another legend we learn that when Count Boniface, Lord of Milan, went to the crusades, his child, born during his absence, was devoured in its cradle by a huge serpent which ravaged the country. On his return, Count Boniface went in search of the monster, and found it with a child in its mouth. He attacked and slew the creature, but at the cost of his own life. Hence it is said his posterity bore the serpent and child as their ensign. A third legend is referred to under Wyvern (which see).

Menestrier says that the first Lords of Milan were called after their castle in Angleria, in Latin anguis, and that these are only the armes parlantes of their name. * Be this as it may, "Lo Squamoso Biscion"

(the scaly snake) was adopted by all the Visconti lords, and by their successors of the House of Sforza.

[paragraph continues] And again in the same poem (cant. iii. 26. Hoole's translation):

[paragraph continues] Dante also refers in "Purgatorio" to this celebrated device.

The "three coiled snakes," which appear in

|

The arms are: Azure three snakes coiled or encircled two and one, or.

Popular legend, however, ascribes their origin to the transformation of a multitude of snakes into stone by St. Hilda, an ancient Saxon princess. The legend is referred to by Sir Walter Scott in "Marmion":

[paragraph continues] It is, however, more than likely that the arms suggested the legend of the miracle.

The ancient myth of the deaf adder seems to have been a favourite illustration of the futility of unwelcome counsel.

"Pleasure and revenge have ears more deaf than adders

To the voice of any true decision."

Troilus and Cressida, Act ii. sc. 2.

"He flies me now—nor more attends my pain

Than the deaf adder needs the charmer's strain."

Orlando Furioso, cant. xxxii. 19.

(Hoole's translation.)

A serpent or adder stopping his ears, by some writers termed "an adder obturant his ear," from the Latin obturo, to shut or stop, is a very ancient idea. It is said that the asp or adder, to prevent his hearing unwelcome truths, puts one ear to the ground and stops the other with his tail, a device suggested by Psalm lviii. 4, 5: "They are like the deaf adder that stoppeth her ear; which will not hearken to the voice of charmers, charming never so wisely."

Alessandro d’Alessandri (+ 1523), a lawyer of Naples, of extensive learning, and a member of the Neapolitan Academy, took for device a serpent stopping its ears, and the motto, "Ut prudentia vivam" ("That I may live wisely"), implying that as the serpent by this means refuses to hear the voice of the charmer, so the wise man imitates the prudence of the reptile and refuses to listen to the words of malice and slander.

It is said that the cerastes hides in sand that it may bite the horse's foot and get the rider thrown. In allusion to this belief, Jacob says, "Dan shall be . . . an adder in the path, that his rider shall fall backward" (Gen. xlix. 17).

Asp.—According to Sir Gardiner Wilkinson, the ancient Egyptian kings wore the asp, the emblem of royalty, as an ornament on the forehead. It appears on the front of the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt.

Many terms have been invented by the heralds to express the positions serpents may assume in arms. Berry's "Encyclopædia of Heraldry" illustrates over thirty positions, the terms of blazon of which it is impossible to comprehend, and hardly worth the inquiry. Few of these terms are, however, met with in English heraldry.

Two serpents erect in pale, their tails "rowed" (twisted or knotted) together, are figured in the arms of Caius College, Cambridge. In the words of the old grant, they are blazoned "gold, serried with

flowers gentil, a sengreen (or houseleek) in chief, over the heads of two whole serpents in pale, their tails knit together (all in proper colour), resting upon a square marble stone vert, between a book sable, garnish’t gul, buckled, or."

Fruiterers’ Company of London.—On a mount in base vert, the tree of Paradise environed with the serpent between Adam and Eve, all proper. Motto: Arbor vitæ Christus, fructus perfidem gustamus.

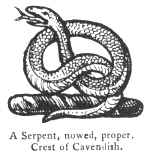

Nowed signifies tied or knotted, and is said of a serpent, wyvern, or other creature whose body or tail is twisted like a knot.

Annodated, another term for nowed; bent in the form of the letter S, the serpents round the caduceus of Mercury may be said to be annodated.

Torqued, torgant, or targant (from the Latin torqueo, to wreathe), the bending and rebending, either in serpents, adders or fish, like the letter S.

Voluted, involved or encircled, gliding, and several terms used in blazon explain

|

In blazoning, the terms snake, serpent, adder, appear to be used indiscriminately.

A serpent nowed, proper, is the crest of Cavendish, Duke of Devonshire.

Gules, three snakes nowed in triangle argent (Ednowain Ap Bradwen, Merionethshire).

Or, three serpents erect wavy sable (Codlen, or Cudlen).

Remora is an old term in heraldry for a serpent entwining.

Serpents are also borne entwined round pillars and rods, &c., and around the necks of children, as in the arms of Vaughan or Vahan Wales: Azure, three boys’ heads affronté, couped at the shoulders proper, crined

|

The amphiptére is a winged serpent. Azure, an amphiptére or, rising between two mountains argent, are the arms of Camoens, the Portuguese poet.

As a symbol in heraldry the serpent does not usually have reference to the mythical creature, as in Early Christian Art, its natural qualities being more generally considered.

116:* "Analysis of Ornament," by Ralph N. Wornum.

117:* That is, Visconti is only a variation of Biscia equivalent to Anguis, Italianised to Angleria.