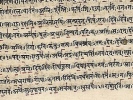

Thirty Minor Upanishads, tr. by K. Narayanasvami Aiyar, [1914], at sacred-texts.com

MAṆDALABRĀHMAṆA-UPANISHAḌ 1

OF

ŚUKLA-YAJURVEḌA

Brāhmaṇa I

Om. The great muni Yājñavalkya went to Aḍiṭyaloka (the sun's world) and saluting him (the Purusha of the sun) said: "O reverend sir, describe to me the Āṭmā-ṭaṭṭva (the ṭaṭṭva or truth of Āṭmā)."

(To which,) Nārāyaṇa (viz., the Purusha of the sun) replied: "I shall describe the eightfold yoga together with Jñāna. The conquering of cold and heat as well as hunger and sleep, the preserving of (sweet) patience and unruffledness ever and the restraining of the organs (from sensual objects)—all these come under (or are) yama. Devotion to one's guru, love of the true path, enjoyment of objects producing happiness, internal satisfaction, freedom from association, living in a retired place, the controlling of the manas and the not longing after the fruits of actions and a state of vairāgya—all these constitute niyama. The sitting in any posture pleasant to one and clothed in tatters (or bark) is prescribed for āsana (posture). Inspiration, restraint of breath and expiration, which have respectively 16, 64 and 32 (māṭrās) constitute prāṇāyāma (restraint of breath). The restraining of the mind from the objects of

senses is praṭyāhāra (subjugation of the senses). The contemplation of the oneness of consciousness in all objects is ḍhyāna. The mind having been drawn away from the objects of the senses, the fixing of the chaiṭanya (consciousness) (on one alone) is ḍhāraṇā. The forgetting of oneself in ḍhyāna is samāḍhi. He who thus knows the eight subtle parts of yoga attains salvation.

"The body has five stains (viz.,) passion, anger, out-breathing, fear, and sleep. The removal of these can be effected respectively by absence of saṅkalpa, forgiveness, moderate food, carefulness, and a spiritual sight of ṭaṭṭvas. In order to cross the ocean of samsāra where sleep and fear are the serpents, injury, etc., are the waves, ṭṛshṇā (thirst) is the whirlpool, and wife is the mire, one should adhere to the subtle path and overstepping ṭaṭṭva 1 and other guṇas should look out for Ṭāraka. 2 Ṭāraka is Brahman which being in the middle of the two eyebrows, is of the nature of the spiritual effulgence of Sachchiḍānanḍa. The (spiritual) seeing through the three lakshyas (or the three kinds of introvision) is the means to It (Brahman). Sushumnā which is from the mūlāḍhāra to brahmaranḍhra has the radiance of the sun. In the centre of it, is kunḍalinī shining like crores of lightning and subtle as the thread in the lotus-stalk. Ṭamas is destroyed there. Through seeing it, all sins are destroyed. When the two ears are closed by the tips of the forefingers, a phūṭkāra (or booming) sound is heard. When the mind is fixed on it, it sees a blue light between the eyes as also in the heart. (This is anṭarlakshya or internal introvision). In the bahirlakshya (or external introvision) one sees in order before his nose at distance of 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 digits, the space of blue colour, then a colour resembling śyāma (indigo-black) and then shining as rakṭa (red) wave and then with the two pīṭa (yellow and orange red) colours. Then he is a yogin. When one looks at the external space, moving

the eyes and sees streaks of light at the corners of his eyes, then his vision can be made steady. When one sees jyoṭis (spiritual light) above his head 12 digits in length, then he attains the state of nectar. In the maḍhyalakshya (or the middle one), one sees the variegated colours of the morning as if the sun, the moon and the fire had joined together in the ākāś that is without them. Then he comes to have their nature (of light). Through practice, he becomes one with ākāś, devoid of all guṇas and peculiarities. At first ākāś with its shining stars becomes to him Para-ākāś as dark as ṭamas itself, and he becomes one with Para-ākāś shining with stars and deep as ṭamas. (Then) he becomes one with Mahā-ākāś resplendent (as) with the fire of the deluge. Then he becomes one with Ṭaṭṭva-ākāś, lighted with the brightness which is the highest and the best of all. Then he becomes one with Sūrya-ākāś (sun-ākāś) brightened by a crore of suns. By practising thus, he becomes one with them. He who knows them becomes thus.

"Know that yoga is twofold through its division into the pūrva (earlier) and the uṭṭara (later). The earlier is ṭāraka and the later is amanaska (the mindless). Ṭāraka is divided into mūrṭi (with limitation) and amūrṭi (without limitation). That is mūrṭi ṭāraka which goes to the end of the senses (or exists till the senses are conquered). That is amūrṭi ṭāraka which goes beyond the two eyebrows (above the senses). Both these should be performed through manas. Anṭarḍṛshti (internal vision) associated with manas comes to aid ṭāraka. Ṭejas (spiritual light) appears in the hole between the two eyebrows. This ṭāraka is the earlier one. The later is amanaska. The great jyoṭis (light) 1 is above the root of the palate. By seeing it, one gets the siḍḍhis aṇimā, etc. Śāmbhavīmuḍrā occurs when the lakshya (spiritual vision) is internal while the (physical) eyes are seeing externally without winking. This is the great science which is concealed in all the tanṭras. When this is known, one does not stay in samsāra. Its worship (or practice) gives salvation. Anṭarlakshya is of

the nature of Jalajyoṭis (or waterjyotis). It is known by the great Ṛshis and is invisible both to the internal and external senses.

"Sahasrāra (viz., the thousand-petalled lotus of the pineal gland) Jalajyoṭis 1 is the anṭarlakshya. Some say the form of Purusha in the cave of buḍḍhi beautiful in all its parts is anṭarlakshya. Some again say that the all-quiescent Nīlakaṇtha accompanied by Umā (his wife) and having five mouths and latent in the midst of the sphere in the brain is anṭarlakshya. Whilst others say that the Purusha of the dimension of a thumb is anṭarlakshya. A few again say anṭarlakshya is the One Self made supreme through introvision in the state of a jīvanmukṭa. All the different statements above made pertain to Āṭmā alone. He alone is a Brahmanishtha who sees that the above lakshya is the pure Āṭmā. The jīva which is the twenty-fifth ṭaṭṭva, having abandoned the twenty-four ṭaṭṭvas, becomes a jīvanmukṭa through the conviction that the twenty-sixth ṭaṭṭva (viz.,) Paramāṭmā is 'I' alone. Becoming one with anṭarlakshya (Brahman) in the emancipated state by means of anṭarlakshya (introvision), jīva becomes one with the partless sphere of Paramākāś.

"Thus ends the first Brāhmaṇa."

Brāhmaṇa II

Then Yājñavalkya asked the Purusha in the sphere of the sun: "O Lord, anṭarlakshya has been described many times, but it has never been understood by me (clearly). Pray describe it to me." He replied: "It is the source of the five elements, has the lustre of many (streaks of) lightning, and has four seats having (or rising from) 'That' (Brahman). In its midst, there arises the manifestation of ṭaṭṭva. It is very hidden and unmanifested. It can be known (only) by one who has got into the boat of jñāna. It is the object of both bahir and anṭar (external and internal) lakshyas. In its midst is absorbed

the whole world. It is the vast partless universe beyond Nāḍa, Binḍu and Kara. Above it (viz., the sphere of agni) is the sphere of the sun; in its midst is the sphere of the nectary moon; in its midst is the sphere of the partless Brahma-ṭejas (or the spiritual effulgence of Brahman). It has the brightness of Śukla (white light) 1 like the ray of lightning. It alone has the characteristic of Śāmbhavī. In seeing this, there are three kinds of ḍṛshti (sight), viz., amā (the new moon), praṭipaṭ (the first day of lunar fortnight), and pūrṇimā (the full moon). The sight of amā is the one (seen) with closed eyes. That with half opened eyes is praṭipaṭ; while that with fully opened eyes is pūrṇimā. Of these, the practice of pūrṇimā should be resorted to. Its lakshya (or aim) is the tip of the nose. Then is seen a deep darkness at the root of the palate. By practising thus, a jyoṭis (light) of the form of an endless sphere is seen. This alone is Brahman, the Sachchiḍānanḍa. When the mind is absorbed in bliss thus naturally produced, then does Śāmbhavī take place. She (Śāmbhavī) alone is called Khecharī. By practising it (viz., the muḍrā), a man obtains firmness of mind. Through it, he obtains firmness of vāyu. The following are the signs: first it is seen like a star; then a reflecting (or dazzling) diamond; 2 then the sphere of full moon; then the sphere of the brightness of nine gems; then the sphere of the midday sun; then the sphere of the flame of agni (fire); all these are seen in order.

"(Thus much for the light in pūrva or first stage.) Then there is the light in the western direction (in the uṭṭara or second stage). Then the lustres of crystal, smoke, binḍu, nāḍa, kalā, star, firefly, lamp, eye, gold, and nine gems, etc. are seen. This alone is the form of Praṇava. Having united Prāṇa and Apāna and holding the breath in kumbhaka, one should fix his concentration at the tip of his nose and making shaṇmukhi 3 with the fingers of both his hands, one hears

the sound of Praṇava (Om) in which manas becomes absorbed. Such a man has not even the touch of karma. The karma of (Sanḍhyāvanḍana or the daily prayers) is verily performed at the rising or setting of the sun. As there is no rising or setting (but only the ever shining) of the sun of Chiṭ (the higher consciousness) in the heart of a man who knows thus, he has no karma to perform. Rising above (the conception of) day and night through the annihilation of sound and time, he becomes one with Brahman through the all-full jñāna and the attaining of the state of unmanī (the state above manas). Through the state of unmanī, he becomes amanaska (or without manas).

"Not being troubled by any thoughts (of the world) then constitutes the ḍhyāna. 1 The abandoning of all karmas constitutes āvāhana (invocation of god). Being firm in the unshaken (spiritual) wisdom constitutes āsana (posture). Being in the state of unmanī constitutes the pāḍya (offering of water for washing the feet of god). Preserving the state of amanaska (when manas is offered as sacrifice) constitutes the arghya (offering of water as oblation generally). Being in state of eternal brightness and shoreless nectar constitutes snāna (bathing). The contemplation of Āṭmā as present in all constitutes (the application to the idol of) sandal. The remaining in the real state of the ḍṛk (spiritual eye) is (the worshipping with) akshaṭa;(non-broken rice). The attaining of Chiṭ (consciousness) is (the worshipping with) flower. The real state of agni (fire) of Chiṭ is the ḍhūpa (burning of incense). The state of the sun of Chiṭ is the ḍīpa (light waved before the image). The union of oneself with the nectar of full moon is the naivēḍya (offering of food, etc.). 2 The immobility in that state (of the ego being one with all) is praḍakshiṇa (going round the image). The conception of 'I am He' is namaskāra (prostration). The silence (then) is the sṭuṭi (praise). The all-contentment (or serenity then) is the visarjana (giving leave to god or finishing worship). (This is

the worship of Āṭmā by all Raja-yogins). He who knows this knows all.

"When the ṭriputi 1 are thus dispelled, he becomes the kaivalya jyoṭis without bhāva (existence) or abhāva (nonexistence), full and motionless, like the ocean without the tides or like the lamp without the wind. He becomes a brahmaviṭ (knower of Brahman) by cognising the end of the sleeping state, even while in the waking state. Though the (same) mind is absorbed in sushupṭi as also in samāḍhi, there is much difference between them. (In the former case) as the mind is absorbed in ṭamas, it does not become the means of salvation, (but) in samāḍhi as the modifications of ṭamas in him are rooted away, the mind raises itself to the nature of the Partless. All that is no other than Sākshi-Chaiṭanya (witness-consciousness or the Higher Self) into which the absorption of the whole universe takes place, inasmuch as the universe is but a delusion (or creation) of the mind and is therefore not different from it. Though the universe appears perhaps as outside of the mind, still it is unreal. He who knows Brahman and who is the sole enjoyer of brāhmic bliss which is eternal and has dawned once (for all in him)—that man becomes one with Brahman. He in whom saṅkalpa perishes has got mukṭi in his hand. Therefore one becomes an emancipated person through the contemplation of Paramāṭmā. Having given up both bhāva and abhāva, one becomes a jīvanmukṭa by leaving off again and again in all states jñāna (wisdom) and jñeya (object of wisdom), ḍhyāna (meditation) and ḍhyeya (object of meditation), lakshya (the aim) and alakshya (non-aim), ḍṛśya (the visible) and aḍṛśya (the non-visible and ūha (reasoning) and apoha (negative reasoning). 2 He who knows this knows all.

"There are five avasṭhās (states), viz.: jāgraṭ (waking), svapna (dreaming), sushupṭi (dreamless sleeping), the ṭurya (fourth) and turyāṭīṭa (that beyond the fourth). The jīva (ego) that is engaged in the waking state becomes attached to the pravṛṭṭi (worldly) path and is the participator of naraka (hell) as the

fruit of sins. He desires svarga (heaven) as the fruit of his virtuous actions. This very same person becomes (afterwards) indifferent to all these saying, "Enough of the births tending to actions, the fruits of which tend to bondage till the end of this mundane existence." Then he pursues the nivṛṭṭi (return) path with a view to attain emancipation. And this person then takes refuge in a spiritual instructor in order to cross this mundane existence. Giving up passion and others, he does only those he is asked to do. Then having acquired the four sāḍhanas (means to salvation), he attains, in the middle of the lotus of his heart, the Reality of anṭarlakshya that is but the Saṭ of Lord and begins to recognise (or recollect) the bliss of Brahman which he had left (or enjoyed) in his sushupṭi state. At last he attains this state of discrimination (thus): 'I think I am the non-dual One only. I was in ajñāna for some time (in the waking state and called therefore Viśva). I became somehow (or involuntarily) a Ṭaijasa (in the dreaming state) through the reflection (in that state) of the affinities of the forgotten waking state; and now I am a Prājña through the disappearance of those two states. Therefore I am one only. I (appear) as more than one through the differences of state and place. And there is nothing of differentiation of class besides me.' Having expelled even the smack of the difference (of conception) between 'I' and 'That' through the thought 'I am the pure and the secondless Brahman', and having attained the path of salvation which is of the nature of Parabrahman, after having become one with It through the ḍhyāna of the sun's sphere as shining with himself, he becomes fully ripened for getting salvation. Saṅkalpa and others are the causes of the bondage of the mind; and the mind devoid of these becomes fit for salvation. Possessing such a mind free from all (saṅkalpa, etc.,) and withdrawing himself from the outer world of sight and others and so keeping himself out of the odour of the universe, he looks upon all the world as Āṭmā, abandons the conception of 'I', thinks I am Brahman' and considers all these as Āṭmā. Through these, he becomes one who has done his duty.

"The yogin is one that has realised Brahman that is all-full beyond ṭurya. They (the people) extol him as Brahman; and becoming the object of the praise of the whole world, he wanders over different countries. Placing the binḍu in the ākāś of Paramāṭmā and pursuing the path of the partless bliss produced by the pure, secondless, stainless, and innate yoga sleep of amanaska, he becomes an emancipated person. Then the yogin becomes immersed in the ocean of bliss. When compared to it, the bliss of Inḍra and others is very little. He who gets this bliss is the supreme yogin.

"Thus ends the second Brāhmaṇa."

Brāhmaṇa III

The great sage Yājñavalkya then asked the Purusha in the sphere (of the sun): "O Lord, though the nature of amanaska has been defined (by you), yet I forget it (or do not understand it clearly). Therefore pray explain it again to me." Accordingly the Purusha said: "This amanaska is a great secret. By knowing this, one becomes a person who has done his duty. One should look upon it as Paramāṭmā, associated with Śāmbhavīmuḍrā and should know also all those that can be known through a (thorough) cognition of them. Then seeing Parabrahman in his own Āṭma as the Lord of all, the immeasurable, the birthless, the auspicious, the supreme ākāś, the supportless, the secondless the only goal of Brahma, Vishṇu and Ruḍra and the cause of all and assuring himself that he who plays in the cave (of the heart) is such a one, he should raise himself above the dualities of existence and non-existence; and knowing the experience of the unmanī of his manas, he then attains the state of Parabrahman which is motionless as a lamp in a windless place, having reached the ocean of brāhmic bliss by means of the river of amanaska-yoga through the destruction of all his senses. Then he resembles a dry tree. Having lost all (idea of) the universe through the disappearance of growth, sleep, disease, expiration and inspiration, his body being always steady, he comes to have a supreme quiescence, being devoid of the movements of

his manas and becomes absorbed in Paramāṭma. The destruction of manas takes place after the destruction of the collective senses, like the cow's udder (that shrivels up) after the milk has been drawn. It is this that is amanaska. By following this, one becomes always pure and becomes one that has done his duty, having been filled with the partless bliss by means of the path of ṭāraka-yoga through the initiation into the sacred sentences 'I am Paramāṭmā,' 'That art thou,' 'I am thou alone,' 'Thou art I alone,' etc.

"When his manas is immersed in the ākāś and he becomes all-full, and when he attains the unmanī state, having abandoned all his collective senses, he conquers all sorrows and impurities through the partless bliss, having attained the fruits of kaivalya, ripened through the collective merits gathered in all his previous lives and thinking always 'I am Brahman,' becomes one that has done his duty. 'I am thou alone. There is no difference between thee and me owing to the fullness of Paramāṭmā.' Saying thus, he (the Purusha of the sun) embraced his pupil 1 and made him understand it.

"Thus ends the third Brāhmaṇa."

Brāhmaṇa IV

Then Yājñavalkya addressed the Purusha in the sphere (of the sun) thus: "Pray explain to me in detail the nature of the fivefold division of ākāś." He replied: "There are five (viz.): ākāś, parākāś, mahākāś, sūryākāś, and paramākāś. That which is of the nature of darkness, both in and out is the first ākāś. That which has the fire of the deluge, both in and out is truly mahākāś. That which has the brightness of the sun, both in and out is sūryākāś. That brightness which is indescribable, all-pervading and of the nature of unrivalled bliss is paramākāś. By cognising these according to this description, one becomes of their nature. He is a yogin only in name, who does not cognise well the nine chakras, the six āḍhāras, the three lakshyas and the five ākāś. Thus ends the fourth Brāhmaṇa."

Brāhmaṇa V

"The manas influenced by worldly objects is liable to bondage; and that (manas) which is not so influenced by these is fit for salvation. Hence all the world becomes an object of chiṭṭa; whereas the same chiṭṭa when it is supportless and well-ripe in the state of unmanī, becomes worthy of laya (absorption in Brahman). This absorption you should learn from me who am the all-full. I alone am the cause of the absorption of manas. The manas is within the jyoṭis (spiritual light) which again is latent in the spiritual sound which pertains to the anāhaṭa (heart) sound. That manas which is the agent of creation, preservation, and destruction of the three worlds—that same manas becomes absorbed in that which is the highest seat of Vishṇu; through such an absorption, one gets the pure and secondless state, owing to the absence of difference then. This alone is the highest truth. He who knows this, will wander in the world like a lad or an idiot or a demon or a simpleton. By practising this amanaska, one is ever contented, his urine and fæces become diminished, his food becomes lessened: he becomes strong in body and his limbs are free from disease and sleep. Then his breath and eyes being motionless, he realises Brahman and attains the nature of bliss.

"That ascetic who is intent on drinking the nectar of Brahman produced by the long practice of this kind of samāḍhi, becomes a paramahamsa (ascetic) or an avaḍhūṭa (naked ascetic). By seeing him, all the world becomes pure, and even an illiterate person who serves him is freed from bondage. He (the ascetic) enables the members of his family for one hundred and one generations to cross the ocean of samsāra; and his mother, father, wife, and children—all these are similarly freed. Thus is the Upanishaḍ. Thus ends the fifth Brāhmaṇa."

Footnotes

243:1 Maṇdala means sphere. As the Purusha in the maṇdala or sphere of the sun gives out this Upanishaḍ to Yājñavalkya, hence it is called Maṇdala-Brāhmaṇa. It is very mystic. There is a book called Rājayoga Bhāshya which is a commentary thereon; in the light of it which is by some attributed to Śri Saṅkarāchārya, notes are given herein.

244:1 Comm.: Rising above the seven Prāṇas, one should with introvision cognise in the region of Ākās, Ṭamas and should then make Ṭamas get into Rajas, Rajas into Saṭṭva, Saṭṭva into Nārāyaṇa and Nārāyaṇa, into the Supreme One.

244:2 Ṭāraka is from tr., to cross, as it enables one to cross samsāra. The higher vision is here said to take place in a centre between the eyebrows—probably in the brain.

245:1 The commentator puts it as 12 digits above the root of the palate—perhaps the Ḍvāḍasānṭa or twelfth centre corresponding to the pituitary body.

246:1 The commentator to support the above that anṭarlakshya, viz., Brahman is jala- or water-jyoṭis quotes the Prāṇāyāma-Gāyaṭrī which says: "Om Āpojyoṭī-raso’amṛṭam-Brahma, etc."—Apo-jyoṭis or water-jyoṭis is Brahman.

247:1 Comm.: Śukla is Brahman.

247:2 The original is, 'Vajra-Ḍarpaṇam.'

247:3 Shaṇmukhi is said to be the process of hearing the internal sound by closing the two ears with the two thumbs, the two eyes with the two forefingers, the two nostrils with the two middle fingers, and the mouth with the remaining two fingers of both hands.

248:1 In this paragraph, the higher or secret meaning is given of all actions done in the pūjā or worship of God in the Hinḍū houses as well as temples. Regarding the clothing of the idol which is left out here, the commentator explains it as āvaraṇa or screen.

248:2 Here also the commentator brings in nīrājana or the waving of the light before the image. That is according to him, the idea, "I am the self-shining."

249:1 The Triputi are the three, the knower, the known and the knowledge. Comm.: Ḍhyāna and others stated before wherein the three distinctions are made.

249:2 Ūha and apoha—the consideration of the pros and cons.

252:1 This is a reference to the secret way of imparting higher truth.