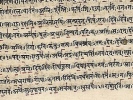

Thirty Minor Upanishads, tr. by K. Narayanasvami Aiyar, [1914], at sacred-texts.com

ḌHYĀNABINḌU-UPANISHAḌ 1

OF

SĀMAVEḌA

Even if sin should accumulate to a mountain extending over many yojanas (distance), it is destroyed by ḍhyānayoga. At no time has been found a destroyer of sins like this. Bījākshara (seed-letter) is the supreme binḍu. Nāḍa (spiritual sound) is above it. When that nāḍa ceases along with letter, than the nāḍa-less is supreme state. That yogin who considers as the highest that which is above nāḍa, which is anāhaṭa, 2 has all his doubts destroyed. If the point of a hair be divided into one-hundred thousand parts, this (nāḍa) is one-half of that still further divided; and when (even) this is absorbed, the yogin attains to the stainless Brahman. One who is of a firm mind and without the delusion (of sensual pleasures) and ever resting in Brahman, should see like the string (in a rosary of beads) all creatures (as existing) in Āṭmā like odour in flowers, ghee in milk, oil in gingelly seeds and gold in quartz. Again just as the oil depends for its manifestation upon gingelly seeds and odour upon flowers, so does the Purusha depend for its existence upon the body, both external and internal. The tree is with parts and its shadow is without parts but with and without parts, Āṭmā exists everywhere.

The one akshara (letter Om) should be contemplated upon as Brahman by all who aspire for emancipation. Pṛṭhivī, agni, ṛgveḍa, bhūḥ and Brahmā—all these (are absorbed) when Akāra

[paragraph continues] (A), the first amśa (part) of praṇava (Om) becomes absorbed. Anṭariksha, yajurveḍa, vāyu, bhuvaḥ and Vishṇu, the Janārḍana—all these (are absorbed) when Ukāra (U), the second amśa of praṇava becomes absorbed. Ḍyur, sun, sāmaveḍa, suvaḥ and Maheśvara—all these (are absorbed) when Makāra (M), the third amśa of praṇava becomes absorbed. Akāra is of (pīṭa) yellow colour and is said to be of rajoguṇa; Ukāra is of white colour and of saṭṭvaguṇa; Makāra is of dark colour and of ṭamoguṇa. He who does not know Omkāra as having eight aṅgas (parts), four pāḍas (feet), three sṭhānas (seats) and five ḍevaṭās (presiding deities) is not a Brāhmaṇa. Praṇava is the bow. Āṭmā is the arrow and Brahman is said to be the aim. One should aim at it with great care and then he, like the arrow, becomes one with It. When that Highest is cognised, all karmas return (from him, viz., do not affect him). The Veḍas have Omkāra as their cause. The swaras (sounds) have Omkāra as their cause. The three worlds with (all) the locomotive and the fixed (ones in them) have Omkāra as their cause. The short (accent of Om) burns all sins, the long one is decayless and the bestower of prosperity. United with arḍhamāṭrā (half-metre of Om), the praṇava becomes the bestower of salvation. That man is the knower of the Veḍas who knows that the end (viz., arḍhamāṭrā) of praṇava should be worshipped (or recited) as uninterrupted as the flow of oil and (resounding) as long as the sound of a bell. One should contemplate upon Omkāra as Īśvara resembling an unshaken light, as of the size of a thumb and as motionless in the middle of the pericarp of the lotus of the heart. Taking in vāyu through the left nostril and filling the stomach with it, one should contemplate upon Omkāra as being in the middle of the body and as surrounded by circling flames. Brahma is said to be inspiration; Vishṇu is said to be cessation (of breath), and Ruḍra is said to be expiration. These are the ḍevaṭās of prāṇāyāma. Having made Āṭmā as the (lower) araṇi (sacrificial wood) and praṇava as the upper araṇi, one should see the God in secret through the practice of churning which is ḍhyāna. One should practise restraint of breath as much as it lies in his power along with (the uttering of)

[paragraph continues] Omkāra sound, until it ceases completely. Those who look upon Om as of the form of Hamsa staying in all, shining like crores of suns, being alone, staying in gamāgama (ever going and coming) and being devoid of motion—at last such persons are freed from sin. That manas which is the author of the actions (viz.), creation, preservation and destruction of the three worlds, is (then) absorbed (in the supreme One). That is the highest state of Vishṇu.

The lotus of the heart has eight petals and thirty-two filaments. The sun is in its midst: the moon is in the middle of the sun. Agni is in the middle of the moon: the prabhā (spiritual light) is in the middle of agni. Pītha (seat or centre) is in the midst of prabhā, being set in diverse gems. One should meditate upon the stainless Lord Vāsuḍeva as being (seated) upon the centre of Pītha, as having Śrīvaṭsa 1 (black mark) and Kausṭubha (garland of gems) on his chest and as adorned with gems and pearls resembling pure crystal in lustre and as resembling crores of moons in brightness. He should meditate upon Mahā-Vishṇu as above or in the following manner. (That is) he should meditate with inspiration (of breath) upon Mahā-Vishṇu as resembling the aṭasī flower and as staying in the seat of navel with four hands; then with restraint of breath, he should meditate in the heart upon Brahma, the Grandfather as being on the lotus with the gaura (pale-red) colour of gems and having four faces: then through expiration, he should meditate upon the three-eyed Śiva between the two eyebrows shining like the pure crystal, being stainless, destroying all sins, being in that which is like the lotus facing down with its flower (or face) below and the stalk above or like the flower of a plantain tree, being of the form of all Veḍas, containing one hundred petals and one hundred leaves and having the pericarp full-expanded. There he should meditate upon the sun, the moon and the agni, one above another. Passing above through the lotus which has the brightness of the sun, moon and agni, and taking its Hrīm bīja (letter), one leads his Āṭmā firmly. He is the knower of Veḍas

who knows the three seats, the three māṭrās, the three Brahmās, the three aksharas (letters) and the three māṭrās associated with the arḍhamāṭrā. He who knows that which is above binḍu, nāḍa and kalā as uninterrupted as the flow of oil and (resounding) as long as the sound of a bell—that man is a knower of the Veḍas. Just as a man would draw up (with his mouth) the water through the (pores of the) lotus-stalk, so the yogin treading the path of yoga should draw up the breath. Having made the lotus-sheath of the form of arḍhamāṭrā, one should draw up the breath through the stalk (of the nādis Sushumnā, Idā and Piṅgalā) and absorb it in the middle of the eyebrows. He should know that the middle of the eyebrows in the forehead which is also the root of the nose is the seat of nectar. That is the great place of Brahman.

Postures, restraint of breath, subjugation of the senses ḍhāraṇā, ḍhyāna and samāḍhi are the six parts of yoga. There are as many postures as there are living creatures; and Maheśvara (the great Lord) knows their distinguishing features. Siḍḍha, bhaḍra, simha and paḍma are the four (chief) postures. Mūlāḍhāra is the first chakra. Svāḍhishthāna is the second. Between these two is said to be the seat of yoni (perineum), having the form of Kāma (God of love). In the Ādhāra of the anus, there is the lotus of four petals. In its midst is said to be the yoni called Kāma and worshipped by the siḍḍhas. In the midst of the yoni is the Liṅga facing the west and split at its head like the gem. He who knows this, is a knower of the Veḍas. A four-sided figure is situated above agni and below the genital organ, of the form of molten gold and shining like streaks of lightning. Prāṇa is with its sva (own) sound, having Svāḍhishthāna as its aḍhishthāna (seat), (or since sva or prāṇa arises from it). The chakra Svāḍhishthāna is spoken of as the genital organ itself. The chakra in the sphere of the navel is called Maṇipūraka, since the body is pierced through by vāyu like maṇis (gems) by string. The jīva (ego) urged to actions by its past virtuous and sinful karmas whirls about in this great chakra of twelve 1 spokes, so long as it

does not grasp the truth. Above the genital organ and below the navel is kanḍa of the shape of a bird's egg. There arise (from it) nādis seventy-two thousand in number. Of these seventy-two are generally known. Of these, the chief ones are ten and carry the prāṇas. Idā, Piṅgalā, Sushumnā, Gānḍhārī, Hasṭijihvā, Pasha, Yaśasvinī, Alambusā, Kuhūḥ and Śāṅkhinī are said to be the ten. This chakra of the midis should ever be known by the yogins. The three nādis Ida, Piṅgalā and Sushumnā are said to carry prāṇa always and have as their ḍevaṭās, moon, sun and agni. Idā is on the left side and Piṅgalā on the right side, while the Sushumnā is in the middle. These three are known to be the paths of prāṇa. Prāṇa, Apāna, Samāna, Uḍāna, and Vyāna; Naga, Karma, Kṛkara, Ḍevaḍaṭṭa and Ḍhanañjaya; of these, the first five are called prāṇas, etc., and last five Naga, etc. are called vāyus (or sub-prāṇas). All these are situated (or run along) the one thousand nādis, (being) in the form of (or producing) life. Jīva which is under the influence of prāṇa and apāna goes up and down. Jīva on account of its ever moving by the left and right paths is not visible. Just as a ball struck down (on the earth) with the bat of the hand springs up, so jīva ever tossed by prāṇa and apāna is never at rest. He is knower of yoga who knows that prāṇa always draws itself from apāna and apāna draws itself from prāṇa, like a bird (drawing itself from and yet not freeing itself) from the string (to which it is tied).

The jīva comes out with the letter Ha and gets in again with the letter Sa. Thus jīva always utters the manṭra 'Ham-sa,' 'Hamsa'. The jīva always utters the manṭra twenty-one thousand and six hundred times in one day and night. This is called Ajapā Gāyaṭrī and is ever the bestower of nirvāṇa to the yogins. Through its very thought, man is freed from sins. Neither in the past nor in the future is there a science equal to this, a japa equal to this or a meritorious action equal to this. Parameśvarī (viz., kunḍalinī śakṭi) sleeps shutting with her mouth that door which leads to the decayless Brahma-hole. Being aroused by the contact of agni with manas and prāṇa, she takes the form of a needle and pierces up through Sushumnā. The

yogin should open with great effort this door which is shut. Then he will pierce the door to salvation by means of kunḍalinī. Folding firmly the fingers of the hands, assuming firmly the Paḍma posture, placing the chin firmly on the breast and fixing the mind in ḍhyāṇa, one should frequently raise up the apāna, fill up with air and then leave the prāṇa. Then the wise man gets matchless wisdom through (this) śakṭi. That yogin who assuming Paḍma posture worships (i.e., controls) vāyu at the door of the nādis and then performs restraint of breath is released without doubt. Rubbing off the limbs the sweat arising from fatigue, abandoning all acid, bitter and saltish (food), taking delight in the drinking of milk and rasa, practising celibacy, being moderate in eating and ever bent on yoga, the yogin becomes a siḍḍha in little more than a year. No inquiry need be made concerning the result. Kuṇdalinī śakṭi, when it is up in the throat, makes the yogi get siḍḍhi. The union of prāṇa and apāna has the extinction of urine and fæces.

One becomes young even when old through performing mūlabanḍha always. Pressing the yoni by means of the heels and contracting the anus and drawing up the apāna—this is called mūlabanḍha. Uddiyāṇa banḍha is so called because it is (like) a great bird that flies up always without rest. One should bring the western part of the stomach above the navel. This Uddiyāṇa banḍha is a lion to the elephant of death, since it binds the water (or nectar) of the ākāś which arises in the head and flows down. The Jālanḍhara banḍha is the destroyer of all the pains of the throat. When this Jālanḍhara banḍha which is destroyer of the pains of the throat is performed, then nectar does not fall on agni nor does the vāyu move. When the tongue enters backwards into the hole of the skull, then there is the muḍrā of vision latent in the eyebrow called khecharī. He who knows the muḍrā, khecharī has not disease, death, sleep, hunger, thirst, or swoon. He who practises this muḍrā is not affected by illness or karma; nor is he bound by the limitations of time. Since chiṭṭa moves in the kha (ākāś) and since the tongue has entered (in the muḍrā) kha (viz., the hole in the mouth), therefore the muḍrā is called khecharī and worshipped by

the siḍḍhas. He whose hole (or passage) above the uvula is closed (with the tongue backwards) by means of khecharīmuḍrā never loses his virility, even when embraced by a lovely woman. Where is the fear of death, so long as the binḍu (virility) stays in the body. Binḍu does not go out of the body, so long as the khecharīmuḍrā is practised. (Even) when binḍu comes down to the sphere of the perineum, it goes up, being prevented and forced up by violent effort through yonimuḍrā. This binḍu is twofold, white and red. The white one is called śukla and the red one is said to contain much rajas. The rajas which stays in yoni is like the colour of a coral. The binḍu stays in the seat of the genital organs. The union of these two is very rare. Binḍu is Śiva and rajas is śakṭi. Binḍu is the moon and rajas is the sun. Through the union of these two is attained the highest body; when rajas is roused up by agitating the śakṭi through vāyu which unites with the sun, thence is produced the divine form. Śukla being united with the moon and rajas with the sun, he is a knower of yoga who knows the proper mixture of these two. The cleansing of the accumulated refuse, the unification of the sun and the moon and the complete drying of the rasas (essences), this is called mahāmuḍrā. Placing the chin on the breast, pressing the anus by means of the left heel, and seizing (the toe of) the extended right leg by the two hands, one should fill his belly (with air) and should slowly exhale. This is called mahāmuḍrā, the destroyer of the sins of men.

Now I shall give a description of Āṭmā. In the seat of the heart is a lotus of eight petals. In its centre is jīvāṭmā of the form of jyoṭis and atomic in size, moving in a circular line. In it is located everything. It knows everything. It does everything. It does all these actions attributing everything to its own power, (thinking) I do, I enjoy, I am happy, I am miserable, I am blind, I am lame, I am deaf, I am mute, I am lean, I am stout, etc. When it rests on the eastern petal which is of śveṭa (white) colour, then it has a mind (or is inclined) to ḍharma with bhakṭi (devotion). When it rests on the southeastern petal, which is of rakṭa (blood colour), then it is inclined

to sleep and laziness. When it rests on the southern petal, which is of kṛshṇa (black) colour, then it is inclined to hate and anger. When it rests on the south-western petal which is of nīla (blue) colour, then it gets desire for sinful or harmful actions. When it rests on the western petal which is of crystal colour, then it is inclined to flirt and amuse. When it rests on the north-western petal which is of ruby colour, then it has a mind to walk, rove and have vairāgya (or be indifferent). When it rests on, the northern petal which is pita (yellow) colour, then it is inclined to be happy and to be loving. When it rests on the north-eastern petal which is of vaidūrya (lapis lazuli) colour, then it is inclined to amassing money, charity and passion. When it stays in the interspace between any two petals, then it gets the wrath arising from diseases generated through (the disturbance of the equilibrium of) vāyu, bile and phlegm (in the body). When it stays in the middle, then it knows everything, sings, dances, speaks and is blissful. When the eye is pained (after a day's work), then in order to remove (its) pain, it makes first a circular line and sinks in the middle. The first line is of the colour of banḍhūka flower (Bassia). Then is the state of sleep. In the middle of the state of sleep is the state of dream. In the middle of the state of dream, it experiences the ideas of perception, Veḍas, inference, possibility, (sacred) words, etc. Then there arises much fatigue. In order to remove this fatigue, it circles the second line and sinks in the middle. The second is of the colour of (the insect) Inḍragopa (of red or white colour). Then comes the state of dreamless sleep.

During the dreamless sleep, it has only the thought connected with Parameśvara (the highest Lord) alone. This state is of the nature of eternal wisdom. Afterwards it attains the nature of the highest Lord (Parameśvara). Then it makes a round of the third circle and sinks in the middle. The third circle is of the colour of paḍmarāga (ruby). Then comes the state of ṭurya (the fourth). In ṭurya, there is only the connection of Paramāṭmā. It attains the nature of eternal wisdom. Then one should gradually attain the quiescence of buḍḍhi with

self-control. Placing the manas in Āṭmā, one should think of nothing else. Then causing the union of prāṇa and apāna, he concentrates his aim upon the whole universe being of the nature of Āṭma. Then comes the state of turyāṭīṭa (viz., that state beyond the fourth). Then everything appears as bliss. He is beyond the pairs (of happiness and pains, etc.). He stays here as long as he should wear his body. Then he attains the nature of Paramāṭmā and attains emancipation through this means. This alone is the means of knowing Āṭmā.

When vāyu (breath) which enters the great hole associated with a hall where four roads meet gets into the half of the well-placed triangle, 1 then is Achyuṭa (the indestructible) seen. Above the aforesaid triangle, one should meditate on the five bīja (seed) letters of (the elements) pṛṭhivī, etc., as also on the five prāṇas, the colour of the bījas and their position. The letter य 2 is the bīja of prāṇa and resembles the blue cloud. The letter र is the bīja of agni, is of apāna and resembles the sun. The letter ल is the bīja of pṛṭhivī, is of vyāna and resembles banḍhūka flower. The letter व is the bīja of jīva (or vayu), is of udāna and is of the colour of the conch. The letter ह is the bīja of ākāś, is of samāna, and is of the colour of crystal. Prāṇa stays in the heart, navel, nose, ear, foot, finger, and other places, travels through the seventy-two thousand nādis, stays in the twenty-eight crores of hair-pores and is yet the same everywhere. It is that which is called jīva. One should perform the three, expiration, etc., with a firm will and great control: and drawing in everything (with the breath) in slow degrees, he should bind prāṇa and apāna in the cave of the lotus of the heart and utter praṇava, having contracted his throat and the genital organ. From the Mūlāḍhāra (to the head) is the Sushumnā resembling the shining thread of the lotus. The nāḍa is located in the Vīṇāḍaṇda, (spinal column); that sound from its middle resembles (that of) the conch, etc. When it goes to the hole of the ākāś, it resembles that of the peacock. In the middle of the cave of the

skull between the four doors shines Āṭmā, like the sun in the sky. Between the two bows in the Brahma-hole, one should see Purusha with śakṭi as his own Āṭmā. Then his manas is absorbed there. That man attains kaivalya who understands the gems, moonlight, nāḍa, binḍu, and the seat of Maheśvara (the great Lord).

Thus is the Upanishaḍ.

Footnotes

202:1 The Upanishaḍ of the seed of meditation.

202:2 Of the heart.

204:1 The black mark on the breast standing for mūlaprakṛṭi and the garland for the five elements.

205:1 In other places, it is ten.

210:1 Probably it refers to the triangle of the initiates.

210:2 There seems to be some mistake in the original.