Sacred Texts Evil Index Previous Next

Buy this Book at Amazon.com

The Evil Eye, by Frederick Thomas Elworthy, [1895], at sacred-texts.com

IN further pursuing this subject, it must be borne in mind that besides the direct influences of fascination, including those of simple bodily presence, breathing, or touching, there is a whole class of operations directly connected with it, comprehended in the terms Magic, Enchantment, Witchcraft.

A great authority, 63 who has dealt exhaustively with the subject of the Occult Sciences, including Omens, Augury, and Astrology, does not even allude to the belief in the evil eye, which we take to be the basis and origin of the Magical Arts. About these the earliest known writings and the most ancient monuments give abundant evidence. Dr. Tylor calls the belief in magic "one of the most pernicious delusions that ever vexed mankind"; and considering magic merely as the handmaid, or the tool, of envy, this description accords well with that of Bacon, as the vilest and most depraved of all "affections."

The practice of magic as defined by Littré, "Art prétendu de produire des effets contre l'ordre de la nature," began with the lowest known stages of civilisation; and although amongst most

savage races it is still the chief part of religion, 64 yet it is not to be taken in all cases as the measure of the civilisation of the people practising it. The reason we assign is, that outward circumstances, such as local natural features, or climate, tend to make the mental condition of certain people specially susceptible of feelings, upon which magical arts can exert an influence altogether out of proportion to the culture of the persons affected. In fact, the more imaginative races, those who have been led to adopt the widest pantheon, have been mostly those upon whom magic has made the most impression; and what was once, and among certain races still is, a savage art, lived on, grew vigorously, and adopted new developments, among people in their day at the head of civilisation. Thus it has stood its ground in spite of all the scoffs of the learned, and the experimental tests of so-called scientific research, until we may with confidence assert that many practices classed as occult, and many beliefs which the educated call superstitious, are still performed and held firmly by many amongst ourselves, whom we must not brand as ignorant or uncultured. No doubt the grosser forms of enchantment and sorcery have passed away; no doubt there is much chicanery in the doings of modern adepts; yet, call it superstition or what we may, there are acts performed every day by Spiritualists, Hypnotists, Dowsers and others, which may well fall within the term Magic; yet the most sceptical is constrained to admit, that in some cases an effect is produced which obliges us to omit the word prétendu from our definition.

We cannot explain how, but undoubtedly there is in certain individuals a faculty, very occult, by which the divining rod does twist in the grasp of persons whose honour and good faith are beyond suspicion. The writer has seen the hazel twig twist in the hands of his own daughter, when held in such a position that no voluntary action on her part could possibly affect it. Moreover, a professional Dowser makes no mystery or hocus-pocus about it; he plainly declares he does not know how, or why, the twig or watch-spring moves when he passes over water; nor can he even teach his own sons to carry on his business. Of all arts we may say of his, nascitur, non fit.

Again, there are certain phenomena in thought-reading, which are well-established facts, clear to our senses. Above all, there are the strange powers possessed by Hypnotists over their patients, which we can no more explain than we can that minutely recorded act of the Witch of Endor 65 who "brought up" Samuel, and instantly discovered thereby that Saul himself was with her. Without believing either in magic or the evil eye, the writer fully agrees that "much may be learnt" 66 from a study of the belief, and of the many practices to which it has given rise. It is needful, however, to approach the subject with an open, judicial mind, and not to reject all, like the "Pharisees of Science," 67 that our superior understanding is unable to explain. Our senses, our experience, alike tell us that there exist many facts and appearances, which appealed strongly to the despised judgment of our forefathers, rude and

cultured alike, which never have been either disproved or explained, and some of these facts have been held as firm articles of belief in all ages.

Mr. De Vere 68 expresses precisely what we mean when he says of the imaginative, rather than the critical mind of our chivalrous ancestors of the Middle Ages, that "they delightedly believed much that many modern men unreasonably disbelieve to show their cleverness." 69

It is easy, and the failure of modern science has made it safe, to call everything we cannot understand contemptible superstition. It is however satisfactory and even consolatory, in pursuing our subject, to know that the same word superstition has been applied by "superior persons," indifferently and impartially, to the most sacred doctrines of Christianity, to the belief in our Lord's miracles, to most solemn mysteries, and creeds other than those of our infallible selves, to the magic omens and portents which many believe in, and to the incantations or enchantments of charlatans, wizards, and sorcerers. 70

The more, however, we study with unbiassed mind the subjects which are called occult, the more evident will it become, even to the least advanced or enlightened amongst us, that there is a whole world

of facts, operations, and conditions, with which our human senses and powers of comprehension are quite incapable of dealing. This has certainly been the experience of all people in all ages; we see in his magic but the feeble efforts of feeble man to approach and to step over the boundary his senses can appreciate, into what is intended to be, and must always remain, beyond his ken-essentially the supernatural.

Man, having come to associate in thought those things which he found by experience to be connected in fact, proceeded erroneously to invert this action, and to conclude that association in thought must involve similar connection in reality. 71

Here no doubt we have the true reason for that association of ideas with facts which a recent author 72 calls Sympathetic Magic. He says: "One of the principles of this is that any effect may be produced by imitating it." So concise a definition may well be borne in mind, for we are told that it lies at the very foundation of human reason, and of unreason also. We Christians, however, certainly cannot agree to call this association of ideas with facts a superstition in the conventional sense; for we must see that the principle, perhaps to suit our humanity and our limited reason, has been appointed and adopted for our most sacred rites. Surely in the act of baptism we hope for the spiritual effect we imitate or typify by the actual use of water. So in that highest of our sacraments we spiritually eat and drink, by the actual consumption of the elements.

Leaving sacred things, which are merely mentioned here, with all reverence, by way of illustration, and to show how association of ideas with facts

is not necessarily superstitious, but a fundamental principle of human ethics, we find that in practice it has nevertheless been more often perverted to the accomplishment, actual or fancied, of the basest designs of malignant spite, than to the higher purposes of religion.

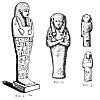

To illustrate his meaning of the term Sympathetic Magic, the author 73 says: "If it is wished to kill a person, an image of him is made and then destroyed, and it is believed that through a certain physical sympathy between the person and his image, the man feels the injuries done to the image as if they were done to his own body, and that when it is destroyed he must simultaneously perish." The idea herein expressed is as old as the hills, and is practised to-day. 74 The ancient Egyptians believed that the ushebtiu or little figures of stone, wood, or pottery (Figs. 1, 2, and 3 which they placed, often in such numbers, in the tombs of their dead, would provide the deceased with servants and attendants to work for him in the nether world, and to fight for him against the many enemies he would there have to combat. Their name signifies respondents, 75 as if to answer to the call for help. The same curious belief is shown in the imitations or re-

presentations of food, such as terra-cotta bread, 76 and other articles placed with the dead for his use and sustenance.

Maspero in his lectures on the "Egyptian Hell" (see a long notice in the Times of August 22, 1887)

Click to enlarge

Figures 1, 2 and 3

76a

dwells upon the reasons which induced the ancients to provide their dead with arms, food, amulets, and slaves, for it was thought the dead would be liable to the corvée as well as the living. Besides all these things the dead were furnished with a funereal

papyrus, now known as the "Book of the Dead," which Maspero, describes as a "Complete Handbook to Hell," giving not only an itinerary of the route but all the spells, incantations, and prayers for each stage of the journey.

The very curious part of these provisions is that idealism seems to have run riot, as though the dead himself, in whose actual existence there was devout belief, would be satisfied with a mere make-believe, or even the picture of the article he needed. They seem to have thought that in the future state the person deceased would be so readily deceived, as to consider himself provided for by the most innocently transparent counterfeits. 77

This remarkable belief in the easy gullibility of the departed was by no means confined to the ancient Egyptians, for among the Chinese is found a custom at present, which, seeing that in China habits change not, we may conclude to be of ancient date.

Archdeacon MacCullagh, long resident in China, says that Chinamen still believe that paper money passes current in the next world as it used to do with them in 'this. They also believe that as the person is dead, so must his money be with which he is to be furnished in the place to which he has gone. They therefore kill the money for him by burning it, in order that he may have dead or killed money.

[paragraph continues] Paper currency has been for many centuries abolished in China, but the people will not believe it to be so in the world of spirits. They therefore prepare spurious paper money in imitation of the old extinct currency, which they burn at the funeral, and also annually at the grave of their departed relative. The Egyptians did almost the same thing: they broke the arms placed with the dead. This killed them, and set their ghosts free to follow their dead master. 78

Such deception, which they think suitable for the spiritual world, evidently will not do for the present: at the death of a Chinaman, his friends present coins, of small value indeed, but real, to all corners, in order to make friends for the departed who may possibly meet him in the place where he is gone. The terra-cotta cakes at the Ashmolean Museum, so like modern Neapolitan loaves, must be such as would be placed with the dead man, by way of satisfying his appetite on his journey to the happy hunting grounds.

Nor can we say that this notion of being able to deceive the dwellers in the unseen world is confined to ancient or specially superstitious people, when we see altars in churches, dedicated to departed saints, bedecked in their honour with flowers of painted tin or coloured calico, stuck in sham vases of tinselled wood.

Again, nearer home, when we see the wreaths of beads strung on wires, of tin leaves and tinted flowers placed under glass shades upon the graves in our cemeteries, we wonder if the "Ka," or the

shade of the departed, when it visits the cast-off mortal coil, will be deceived by these cheap counterfeits. We fear we must conclude that such things can only be classed, even in this nineteenth century, as mere examples of the performances of sympathetic magic, to be summed up in the famous words of Erasmus to Sir Thomas More: "Crede ut habes et habes."

In our Somerset County Museum at Taunton is to be seen more than one heart, said to be those of pigs, stuck full of pins

Click to enlarge FIG. 4 |

old belief that the heart is the seat of life, and therefore a fit representative or symbol of a living person. They believed that the heart of the hated person would suffer from the pricking inflicted upon the pig's heart, and that as the latter dried up and withered, so would the heart and the life of the victim against whom the act was designed.

The Bakongo people "believe the spirit is situated

Click to enlarge FIG. 5 |

A few years ago, also in this same neighbourhood,

an onion was found hidden in a chimney, with a paper stuck round it by numberless pins; on this was written the name of a well-known and highly-respected gentleman, a large employer of labour.

The other day I 81 was at the Court House, East Quantoxhead, and was shown in the chimney of a now disused kitchen--suspended--a sheep's heart stuck full of pins. I think Captain L------ told me that this was done by persons who thought themselves "overlooked" or "ill-wished;" also to prevent the descent of witches down the chimney. . . . The heart is in good preservation.

In 1875 the village of Worle, near Weston-super-Mare, was in a commotion about the death of a "varth o' paigs," and the owner sent for a "wise man" from Taan'tn, who laid it to the charge of four

village wives, all of whom he declared he would bring to the house of the aggrieved party to beg for mercy and forgiveness.

The heart of one of the defunct pigs was stuck full of pins and then thrown on the fire--the owner and his wife sitting by and "waiting for poor old Mrs. ------ to come and ask why they were hurting her." The remarkable coincidence followed these proceedings, that the old woman, who bore a bad reputation for "overlooking," should have met her death by falling into the fire on her own hearth. We are not told how soon this event followed the burning of the heart. 82

Another recent instance in Somerset. An old woman living in the Mendip district had her pig "took bad," and of course at once concluded that it was "overlooked." As usual in such cases, a white witch was applied to. 83 The following is what took place in obedience to his orders.

A sheep's heart was stuck full of pins and roasted before the fire. While this was being done, the assembled people chanted the following incantation:--

It is not this heart I mean to burn,

But the person's heart I wish to turn,

Wishing them neither rest nor peace

Till they are dead and gone.

At intervals, in response to a request of "Put a little more salt on the fire, George," the son of the old woman bewitched, sprinkled the fire, thus adding a ghastly yellow light to the general effect. After this had gone on far into the night, the inevitable "black cat" jumped out from somewhere, and was pronounced to be the fiend which had been exorcised." 84

Closely allied to these practices is that of the maidens in Shropshire, who drop needles and pins into the wells at Wenlock, to arrest and fix the affections of their lovers. 85 Nor is this particular form of sympathetic enchantment, which here in Somerset is a very common one, by any means confined to this country.

A year or two ago a friend showed me in Naples an almost identical object, within a few days of its discovery: the following is his own account of it:--

In 1892 Mr. William Smith, English grocer at Naples, in course of cleaning his house, took down his curtains, and on the top of the valence-board found the object. Mrs. Smith presented it to Mr. Neville Rolfe, knowing that he took an interest in such things. He showed it to his cook, an old man, who was as ignorant and superstitious as ever a Neapolitan could be; and he was so horror-stricken (thinking it had been sent to the house by some evil-disposed person) that he declined to remain in the house unless the object were at once sent out of it! Mr. Rolfe, accordingly, lent it to the Museum at Oxford. It consists of an ordinary Neapolitan green lemon, into which twenty-four clout-headed nails and half a dozen wire nails are stuck, the nails being secured by a string twisted round their heads. The cook asserted that after the thing was made by the witches, they put it above a brazier, and danced round it naked, thus making it of deadly power. Many stories are current in Naples of the efficacy of the incantations practised by the witches, and especially of one who resided in Mergellina, a part of Naples still mainly inhabited by fishermen.

It appears that in Southern Italy the article is so common as to have a regular name, Fattura della

morte (deathmaker), and that it is constantly employed in the same manner, and for the same purpose, as the pig's heart or onion is with us. Fig. 6 is from a drawing of this remarkable object now in the Pitt Rivers Museum. 86 The string or yarn twisted

Click to enlarge

FIG. 6

about the nails, though now blackened by dirt and age, seems to have been originally coloured.

Who can deny that along with the onion as an eatable tuber, which almost certainly came to us from Italy, we may also have received the practice of the fattura della morte?

The winding of the thread or yarn amongst the nails has doubtless its especial meaning, and is certainly a relic of ancient days, for Petronius, writing of certain incantations performed for the purpose of freeing a certain Encolplus from a spell, says: "She then took from her bosom a web of twisted threads of various colours, and bound it on my neck." 87

[paragraph continues] The same custom of tying threads of many colours on the necks of infants as part of a charm against fascination is mentioned by Persius. 88

The foregoing examples are intended to show sympathetic magic in its destructive or evil-working side, but we may easily find instances of its use for beneficent or at least harmless purposes. The idea prevails in various parts of South Wales, where at certain holy wells, each having a separate reputation of its own for specific diseases, the faithful hang a piece of rag, after having rubbed it over the part diseased, upon some special tree or bush near the well, in the belief that the rag absorbs the ailment, and that the sufferer will be cured. One or more of these trees are covered with pieces of rag placed on it by the believers. There is, in some instances, an accompaniment of dropping pins into the well, but it does not appear whether this act has any particular connection with the rag; though it is suggested that the pin or button dropped into the well is a make-believe votive offering to the presiding spirit. There are besides many famous wishing wells, where by the practice of certain acts, such as dropping pins, maidens learn who is to be their lover; also on the other hand ill-wishing is practised; for corks stuck with pins are set afloat in them, and the hearts of enemies are wounded thereby. 89

One of our commonest cures for warts is: "Take a dew-snail and rub it on the wart, then stick the

snail upon a white thorn, and as the snail dries up and 'goes away' so will the wart." 90 Another is: "Steal a piece of fresh raw beef and rub that upon the wart, then bury it where nobody sees, and as the meat perishes, so will the wart." In both these cases secrecy is of the essence of the act--if any one is told or knows what is done, except the person performing, the result will be nothing. Sympathetic medicine is no less an active force than the evil-working magic of which examples have been given. The following recipe, called "The Cure of Wounds by the Powder of Sympathy," is a serious one, and throws light upon the art and science of surgery just two hundred years ago.

Take good English Vitriol which you may buy for 2d. a pound, dissolve it in warm water, using no more than will dissolve it, leaving some of the impurest part at the bottom undissolved, then pour it off and filtre it, which you may do by a coffin of pure gray paper put into a Funnel, or by laying a sheet of gray paper in a sieve, and pouring your water or Dissolution of Vitriol into it by degrees, setting the sieve upon a large Pan to receive the filtred Liquor: when all your Liquor is filtred boyl it in an Earthen vessel glazed, till you see a thin scum upon it; then set in a cellar to cool covering it loosly, so that nothing may fall in: after two or three days standing, pour off the Liquor, and you will find at the bottom and on the sides large and fair green Chrystals like Emerauds: drain off all the water clean from them, and dry them, then spread them abroad in a large flat earthen dish, and expose them to the hot sun on the Dog-days, taking them in at Night and setting them out in the Morning, securing them from the rain; and when the Sun hath calcin'd them to whiteness, beat them to powder and set this powder again in the Sun, stirring it sometimes, and when you see it perfectly white, powder it, and sift it finely, and set it again in the Sun for a day, and you will have a pure white powder, which is the Powder of Sympathy, which put in a glass and stop it close. The next year when the Dog-days come if you have any of this powder left

you may expose it in the Sun, spreading it abroad to renew its vertue by the Influence of the Sunbeams.

The way of curing wounds with it, is to take some of the blood upon a Rag, and put some of the Powder upon the blood, then keep only the wound clean, with a clean Linnen about it, and in a moderate temper betwixt hot and cold, and wrap the Rag with the blood, and keep it either in your Pocket, or in a Box, and the Wound will be healed without any Oyntment or Plaister, and without any pain. But if the wound be somewhat Old and Hot and Inflamed, you must put some of this Powder into a Porringer or Bason full of cold water, and then put anything into it that hath been upon the wound, and hath some of the blood or matter upon it, and it will presently take away all Pain and Inflamation as you see in Sir Kenelm's Relation of Mr. Howard.

To staunch the Blood either of a Wound or bleeding at the Nose, take only some of the Blood upon a Rag, and put some Powder upon it; or take a Bason with fresh water and put some Powder into it; and bath the Nostrils with it. 91

"A few years ago in India, during a cholera scare," a witness tells the writer, "a woman dressed in fantastic style was led by two men up to an infected house, with the usual following of tom-toms and musicians. A fire with much smoke was made outside, and the woman, who represented the cholera spirit, was completely fumigated amidst much ceremony, prayers, and great din. Nothing whatever was done to house or patient; in two days, however, the cholera had ceased."

We also include here all the many harvest customs, the Maypoles, the jacks in the Green, with all their dancing and merrymaking, as being more or less dramatic representations of the ends all these acts and ceremonies were originally intended to produce. Surely the Lord and Lady of the May, the King and Queen of the May, the actual marriage of trees, are something more than mere types or emblems of

animal and vegetable fertility, which, primarily, all these things were believed and intended to procure or to stimulate.

There is abundant evidence that those now practised are survivals of very ancient rituals: that the marriage of Dionysus and Ariadne, said to have been acted every year in Crete, is the forerunner of the little drama acted by the French peasants of the Alps, where a king and queen are chosen on the first of May and are set on a throne for all to see.

Persons dressed up in leaves represent the spirit of vegetation; our Jack in the Green is his personification. In several parts of France and Germany the children dress up a little leaf man, and go about with him in spring, singing and dancing from house to house.

Throughout Europe, the Maypole is supposed to impart a fertilising influence over both women and cattle as well as vegetation.

Sometimes these May trees, and probably our west country 92 Neck, like the ancient Greek Eiresione, were burnt at the end of the year, or when supposed to be dead; and surely it is no unfair inference to assume that such burning was a piece of ritualistic worship of the life-giving Sun, whose bright rays are so needful to the progress of vegetation. Again all the little by-play with the water which occurs in our business of "Crying the Neck," and the throwing water over the priest of the sacred grove in Bengal, with many other examples in several parts of Europe of the sousing with water over the tree, the effigy, or the real person representing the rain spirit, are

but acted imitations of the end desired. The object of preserving the Harvest May, Neck or Eiresione, from one year to another, is that the life-giving presence of the spirit dwelling in it may promote the growth of the crops throughout the season, and when at the end of the year its virtue is supposed to be exhausted, it is replaced by a new one. How widely spread these ideas are found, and among what essentially different races, can be proved by the fact that precisely analogous customs are found in Sweden and Borneo, in India, Africa, North America, and Peru. 93

Referring to sun-worship, mentioned above, there are still remaining amongst us many vestiges, besides those relating to the Beltan fires, 94 in Scotland, Ireland, and Northern England.

An Irish peasant crawls three times round the healing spring, in a circuit that imitates the course of the sun. 95 It is everywhere thought most unlucky to progress in a direction opposite to the course of the sun; indeed so well is this understood that we

have a special word, widdershins, to express the contrary direction. It is a well-known rule of Freemasons not to go against the sun in moving within the Lodge, and there are other plain survivals of sun-worship in other points of masonic ritual. In the Hebrides the people used to march three times from east to west round their crops and their cattle. If a boat put out to sea, it first made three turns in this direction, before starting on its course; if a welcome stranger visited the islands, the people passed three times round their guest. 96 A flaming torch was carried three times round a child daily until it was christened. 97

The old Welsh names for the cardinal points of the sky, the north being the left hand and the south the right, are signs of an ancient practice of turning to the rising sun. 98

In the Highlands of Scotland 99 and in Ireland it was usual to drive cattle through the needfire as a preservative against disease. 100 In these last examples we see customs almost analogous to making the children pass through the fire to Moloch.

We know that our British forefathers were Sun-worshippers,

though the Sun does not appear to have been the chief of their divinities. Lug was the personification of the sun; he was the son of Dagda 101 "the good god," who was "grayer than the gray mist," and he had another son named "Ogma the sun-faced," the patron of writing and prophecy.

It may well be maintained that all our modern notions included in the general term Orientation are but survivals of the once universal sun-worship.

A great authority 102 says that the ceremony of Orientation "unknown in primitive Christianity . . . was developed within its first four centuries."

This statement (and here he differs from his usual practice) is unsupported by any authority; with all deference we would submit that there is much evidence to the contrary. Sun-worship was undoubtedly an abomination to the Jews, but the very facts recorded in connection with Ezekiel's horror (ch. viii. 16) at the idolatry of the twenty-five men who worshipped the sun in the temple of the Lord, show first a careful Orientation of the temple itself, in accordance with the plan the Israelites had learnt in Egypt; and next that general importance attached to the directions of east and west. Thus, although actual sun-worship was considered as idolatry, the Sun was both actually and typically regarded as the almighty life-giving power of nature--giving his own name to the great emanation, the only begotten Son of the Father, the Light of the World, the Sun of Righteousness. Surely these very names speak eloquently of the idea, if not of the practice implied in the term Orientation. Primitive Christianity

will doubtless be admitted to have been developed from the older Judaism, and even if no distinct intimation of any actual ceremony which might be called Orientation can be found among Jewish rites, yet the fact that Daniel (ch. vi. 10) prayed with his windows opened "towards Jerusalem" shows that he attached importance to position, even though Jerusalem, where he believed his God to reside, was situated to the west of Babylon.

It was an ancient custom among the heathen to worship with their faces towards the east. 103 This is confirmed by Clement of Alexandria, who says that the altars and statues of pagan temples were placed at the east end, so that those who came to worship might have their faces towards them. 104 This account scarcely accords with the construction of Egyptian temples, yet we read immediately: "Nevertheless the way of building temples towards the east, so that the doors being opened should receive the rays of the rising sun, was very ancient, and in later ages almost universal." Moreover we know that Orientation in building was an important factor in pagan worship long antecedent to Christianity; while the traditional burial of Christ Himself, looking eastwards, shows that the ceremony of Orientation was at least practised in the earliest days of the Church, though it can be no more called an act of idolatrous sun-worship, than is our still-observed custom of burying our dead with their feet eastwards, so that the body may rise to face the Lord at His second coming in

the east. Here again we see Christianity and heathendom hand in hand, for among the aboriginal Australians, who are still cannibals, the graves have a direction from east to west, and the foot of the grave is toward the rising sun. "If the deceased was a prominent man, a hut is sometimes built over his grave. The entrance, which faces east, has an opening through which a grown person may creep. Near Rockhampton I saw several graves not more than a foot deep, in which the feet were directed towards the rising sun." 105

The care observed by the ancient Egyptians in building their temples properly east and west is remarkable, and while perhaps involving something more, still plainly points to the idea that the sun was the almighty power. Nowhere is this seen more distinctly than in the two rock-hewn temples at Abou Simbel. These are carefully constructed to meet the rising sun upon two anniversaries. The great temple was hewn out to commemorate the victory of Rameses the Great over the Cheta, and was specially dedicated to Ra, the God of Light. 106 The writer was fortunate enough to see the rays at sunrise penetrate to the extreme end, and light up the statues at the innermost part of the sanctuary, on the very anniversary of the famous battle--February 24. 107 The smaller temple also commemorates a victory of Rameses, but evidently at a later

period of the year, as its axis points north of that of its greater companion. All the Egyptian temples are carefully orientated with the sanctuary at the west, so that the sun's rays enter at the east end and light up the sacred statues only on certain dedication days. The same system was adopted by the Greeks, and later by the Romans in their temples. The Roman basilicas were also constructed in like manner, and have thus left their mark on the churches now called Basilicas, where the main entrance--as at St. John Lateran, St. Peter's, S. Paolo fuori le mura, Sta. Maria Maggiore, and others--is at the east, and the sanctuary at the west. These facts all tend to show a general adaptation of what had been good, or unobjectionable, in pagan customs to the requirements of the Christian faith; just as the pagan and Jewish lustrations, ancient and almost universal, were perpetuated in the Christian rite of baptism, both by the example and precept of the Church's divine Master; proving that practical customs, harmless in themselves, were not forbidden, but were consecrated by adoption as sacred ceremonies into the then reformed Jewish worship which we call Christianity. We find, too, that baptism itself was in the early Church closely allied to Orientation, in the position in which the catechumen was placed. 108

It is not generally known that in pagan temples there was a vessel of stone or brass, called περιρραντήριον, filled with holy water, with which all those admitted to the sacrifices were sprinkled, and

beyond this it was not lawful for the profane to pass, 109 until purified by water. By some accounts this vessel was placed at the door of the temple; thus the holy-water stoups, outside the doors of so many of our old churches, are not of Christian origin at all, but merely an adaptation of the lustration used in rites we now call heathen.

Although it was usually considered that a small sprinkling was sufficient, yet sometimes, before participation in the sacred rites, the feet were washed as well as the hands. 110 So also the water was required to be clear and free from all impurities. The Jews used the same rite as the pagans, and were careful to have clean water for their washing of purification, hence St. Paul's expression (Heb. x. 22), "Our hearts sprinkled from an evil conscience, and our bodies washed with pure water." In Ezekiel (xxxvi. 25) we read: "I will sprinkle clean water upon you, and ye shall be clean."

Whether or not Orientation be in idea and in practice a quasi sun-worship, we, who would repel the suggestion of idolatry, have customs, keeping their place amongst us, notwithstanding all our enlightenment and culture, to which no such exception can be applied, for they surely partake of both sun-worship and sympathetic magic.

The very common custom, still maintained, of passing a child afflicted with congenital hernia through a split ash-tree is precisely such a case. The rite has to be performed on a Sunday morning at, or just before, sunrise--the opening must be made in the direction of east and west, for the child

must be passed through it towards the rising sun. 111

Another custom almost similar is reported from Gweek, in the parish of Wendron, Cornwall, 112 where the Tolvan or holed stone was in repute as a means of curing weak or rickety infants, who were brought, often from a distance, to be passed through the hole.

In ancient Greece, such as had been thought to be dead, and on whom funeral rites had been celebrated, but who afterwards recovered, such also as had been long absent in foreign countries, where it was believed they had died, if they should return home, were not permitted to enter into the temple of the Eumenides until after purification. This was done at Athens, by their "being let through the lap of a woman's gown, that so they might seem to be new born."

So in Rome, such as had been thought dead in battle, and afterwards returned home unexpectedly, were not allowed to enter at the door of their own houses, but were received at a passage opened in the roof, 113 and thus, as it were, in full view of the sun.

These rites can be considered as nothing short of dramatic representations of that which it is desired to accomplish, i.e. remedy of congenital or ceremonial imperfection by a new birth.

The homœopathic notion that like produces or

cures like, is by no means new. One of the oldest remedies for a bite, here in England, was a hair of the dog that bit you; or the best way to staunch blood from a wound was to place in it the knife or sword which caused it. A friend of the writer, the Rev. R. P. Murray of Shapwick Vicarage, Dorset, relates that in May 1890, while at Arucas, in Grand Canary, he saw a dog fiercely attack a native boy, and that although he rushed to the boy's assistance, the latter was badly bitten in the hand, and his clothes much torn. The howling of the lad and the shouts of Mr. Murray caused a hue and cry, so that the dog was quickly caught amid much gesticulation and brandishing of knives, which my informant thought were to polish off the beast in no time. Instead of this, however, a handful of his shaggy hair was cut off, and the boy, well knowing what was to be done, held out his bleeding hand: the hair was placed on the wound, a lighted match was applied, and a little fizzled-up heap of animal charcoal remained upon it. No doubt the cautery was a good remedy, but all the virtue was believed by the natives to be in the hair of the dog that caused the wound.

Another curious form of the association of ideas with facts, or rather perhaps of persons with their belongings, is shown in the care which many people take to prevent anything they have owned or used getting into the possession of an enemy.

A South Sea Island chief persisted that he was extremely ill, because his enemies the Happahs had stolen a lock of his hair, and buried it in a plantain leaf for the purpose of killing him. He had offered the Happahs the greater part of his property if they

would but bring back his hair and the leaf, for that otherwise he would be sure to die. 114

It is for this reason that nothing whatever is to be seen but ashes on the spot where gypsies have encamped, unless it be the little peeled stick, left sometimes standing upright in the ground, most likely as a secret signal to friends who may be passing that way. One of these was noted very recently by the writer (Dec. 1893). Everything else is carefully burnt or otherwise made away with.

The aboriginal Australians believe that an enemy getting possession of anything that has belonged to them, can employ it as a charm to produce illness or other injury to the person to whom the article belonged. They are therefore careful to burn up all useless rubbish before leaving a camping ground. Should anything belonging to an unfriendly tribe be found, it is given to the chief, who preserves it as a means of injuring the enemy. This Wuulon, as it is called, is lent to any one who desires to vent his spite against a member of the unfriendly tribe. When thus used as a charm, the Wuulon is rubbed over with emu fat mixed with red clay and tied to the point of a spear-thrower, which is stuck upright in the ground before the camp fire.

The company sit round watching it, but at such a distance that their shadows cannot fall on it. They keep chanting imprecations on the enemy till the spear-thrower, as they say, turns round, and falls in the direction of the tribe the Wuulon belongs to. Hot ashes are then thrown in the same direction with

hissing and curses, and wishes that disease and misfortune may overtake their enemy. 115

One cannot but wonder if the little stick stuck up by our gypsies is in any way connected with this custom. These latter are said to have come from India, and their habit of burning up all refuse after them, like the far-away Australians, seems to point to a common origin. 116

A recent traveller in Australia says that "in order to be able to practise his arts against any black man, the wizard must be in possession of some article that has belonged to him--say, some of his hair or of the food left in his camp, or some similar thing. 117 On Herbert River the natives need only know the name of the person in question, and for this reason they rarely use their proper names in addressing or speaking of each other, but simply their clan names."

Another apt illustration comes from the West Indies. In Demerara it is to-day firmly and widely believed by the negroes and others, that injuries inflicted even upon the defecations of persons will be felt by the individual by whom they were left; and consequently it is often sought thus to punish the author of a nuisance. In 1864 the town of Georgetown was nearly destroyed by fire, and upon close investigation into its origin, it was proved to have been in consequence of some boys who, having

found the excrement of another in a newly-constructed house, said: "Ki! let us burn it; now we make him belly ache"; and accordingly they got some shavings and made a fire over what they had found-the consequence was a vast destruction of property. The foregoing fact can be distinctly substantiated by the writer's informant, who was then a medical officer on the spot. Moreover, the like belief is still held even here in Somerset. About the year 1880 the child of a well-to-do farmer's wife was ill, and in the course of her explanations to the doctor, the mother expressed great displeasure with the nurse, especially at having discovered that she had thrown the child's excrement on the fire, and continuing, said: "You know this is very bad for the baby and ought not to be done, as it causes injury." She could not be drawn out to say what injury or malady was to be expected, but she said enough to show that the belief was commonly and strongly held. This woman is still living, and she and all her family are well known to the writer.

Further inquiry in other quarters completely clears up the question as to the injury to be expected from this proceeding, and very remarkably confirms the story from Demerara. An old midwife, questioned (May 14, 1894) upon this piece of nurse lore, at once said: "’Tis a very bad thing to throw a child's stooling on the fire, 'cause it do give the child such constipation and do hurt it so in his inside." She said she had proved it; she knew it was a bad thing, and had always heard, ever since she was a girl, that it was bad for the child. On the same day Mrs. S------, aged 85, said that when she was a girl at Taunton, she well remembers. people saying that

it was a bad thing, as it gives the children constipation and hurts them; but she did not believe in it. She had not heard anything about it for years now. The day following, Mary W-----, 80, and Anne P-----, 70, two old women in the Workhouse, one a native of Devon, on being asked about it, said: "Lor! did'n you never hear o' that?" Both believed it, and had always heard that it was hurtful to a child. Several other old women--indeed all there were--knew all about it. These inquiries led to the further discovery that the piece of the funis umbilicus should be taken off at the proper time and burnt; that if this is not done, and if it is allowed to drop off naturally, especially if it should fall on the floor, the child will grow into a ------ which, politely expressed, means afflicted with nocturnal enuresis, an uncleanly habit. Squabbles among the women "in the House" are not uncommon, from this cause. Much more might be said as to other reasons given for the careful attention to this operation, especially as to the different treatment of a boy from a girl, but they are wide of our subject, and scarcely desirable for discussion here.

Very strange belief in sympathy, even in the present day, appears in the following:--

A friend of mine, not long ago, told me that the wife of his coachman had been confined some time before the event was expected. He thereupon went to his own cook to tell her to send food to the woman and to render what help she could.

The cook said: "I knew how it would be, sir; it's all along of them lionesses." She repeated the expression, and my friend, not understanding what she meant, inquired what the lionesses had to do with the matter.

"Why, don't you know, sir, that when the lionesses have their cubs very early, women have always a tendency to be brought to bed prematurely?"

She appeared surprised that he had never heard of this "fact"; and on inquiry of a medical friend--or friends--he told me that the superstition seems to be a very prevalent one among the old "Mother Gamps."

One would have supposed this belief must be peculiar to London, the locale of this story, where alone the presence of lionesses can be effective; still the facts are of much interest as a proof of a continued survival. On close inquiry, however, even here in Somerset, there are traces of the like notion. The old women in the Wellington Workhouse say: "If a lioness dies in whelping, the year in which that happens is a bad one for women to be confined in." This belief is quite common; Mrs. M------ the matron has often heard it. All this suggests the idea that the British Lion may be not merely a fanciful object of heraldic blazonry, of which the people know nothing, but that he must be the Totem of our Celtic forefathers.

It is strange that the notion should be so stoutly maintained as to the injury done to a person by burning one thing, while on the other hand it is equally held that a child's milk-teeth, his nails, and hair should be burnt, lest injury come to him through neglect of that precaution. Stranger still is it to find how very widely these old and deep-seated beliefs are entertained by people of races so different as Somerset peasantry and West Indian negroes.

Such facts as we have given above cannot fail to

suggest that the burning of the effigy of a hated person means, at the bottom, a good deal more than a mere demonstration, and at least in times past was thought to injure by actual bodily suffering the person represented.

The student of man tells us that the reason for the reluctance to disclose one's name, was of the same nature as that which makes savages, and nations far above the savage state, feel anxious that an enemy should not get possession of anything identified with one's person as a whole, especially if such enemy is suspected of possessing any skill in handling the terrors of magic. In other words, the anthropologist would say that the name was regarded as part of the person, and having said this, he is usually satisfied that he has definitely disposed of the matter. . . . The whole Aryan family believed at one time, not only that his name was a part of a man, but that it was the part of him which is termed the soul, the breath of life, or whatever you may choose to define it as being. 118

May we not add to this, that what relates to persons may by the same reasoning be applied to things? Hence, of course, comes the belief of the modern Neapolitan, that in the absence of the amulet or charm the mere utterance of its name is equally effective as a protection, and that force is added thereto by the repetition of the name. 119

Professor Rhys says that the Irish "probably treated the name as a substance, but without placing it on one's person, or regarding it as being of one's person, so much as of something put on the person at the will of the name-giving Druid, some time before the person to be named had grown to man's estate." Something of the same kind is found among Australian aborigines. They "have this peculiarity in common with the savages of other countries, that

they never utter the names of the dead, lest their spirits should hear the voices of the living and thus discover their whereabouts." 120 Did not the Witch of Endor "call up" Samuel, that is by uttering his name?

The connection of a man's shadow with his body, as evidenced in the proceedings of Australian savages, is also a very widespread belief at the present time throughout the East amongst the races from which the Australians originally sprang. An injury to a man's shadow, such as stabbing, treading on or striking it, is thought to injure his person in the same degree; and if it is detached from him entirely, as it is believed it may be, he will die.

In the Island of Wetar in the Eastern Archipelago, near Celebes, the magicians profess to make a man ill by stabbing his shadow with a spear, or hacking it with a sword. Sankara, to prove his supernatural powers to the Grand Lama, soared into the air, but as he mounted up, the Grand Lama, perceiving his shadow swaying and wavering on the ground, struck his knife into it, upon which down fell Sankara and broke his neck. 121 The ancient Greeks, too, believed in the intimate association of a man or beast with his shadow. It was thought in Arabia that if a hyena trod on a person's shadow it deprived him of the power of speech; also that if a dog were standing on a roof, and if his shadow falling upon the ground were trodden upon by a hyena, the dog would fall down as if dragged by a rope. Again it was thought, on the other hand, that a dog treading upon the shadow of a hyena rendered the latter dumb. 122

[paragraph continues] Whoever entered the sanctuary of Zeus on Mount Lycæus was believed to lose his shadow and to die within the year. Here in the west country there is an old belief that many have sold their souls to the devil, and that those who do so, lose their shadow--from this it would seem to be thought, that the shadow contains the soul, i.e. the "Ka" of ancient Egypt.

In olden times it was believed in many widely separated countries 123 that a human victim was a necessity for the stability of any important building; indeed the idea was by no means confined to paganism, for we are told that St. Columba 124 found it necessary to bury St. Oran alive beneath the foundation of his monastery, in order to propitiate the spirits of the soil, who demolished at night what had been built during the day.

Here in England, throughout the Middle Ages, the common saying, "There's a skeleton in every house," or, "Every man has a skeleton in his closet," was hardly a figure of speech. The stories of finding the skeletons of faithless monks and nuns walled up alive, 124a seem to have sprung from a much earlier notion; and it is now well established that these are by no means myths, but very facts. At Holsworthy, in North Devon, the parish church was restored in

[paragraph continues] 1845. On taking down the south-west angle wall a skeleton was found imbedded in the stone and mortar. There was every appearance of the body having been buried alive, and hurriedly. A mass of mortar was over the mouth, and the stones were heaped and huddled about the corpse; the rest of the wall had been built properly.

Many similar accounts are given of finds of a like nature in various parts of Germany, and the superstition that walls would not stand without a human victim, existed among Celts, Slavs, Teutons and Northmen. Even so late as 1813 when a Government official went to repair a broken dam on the Elbe, an old peasant sneered at his efforts, and said: "You will never get the dyke to hold unless you first sink an innocent child under its foundations." Several stories are told of parents who sold their children for this purpose, and of others where the victim, often a woman, was kidnapped and built into the foundations.

At the building of the castle of Henneberg a mason had sold his child to be built into the wall. The child had been given a cake, and the father stood on a ladder superintending the work. When the last stone had been put in, the child screamed in the wall, and the man, overwhelmed with self-reproach, fell from the ladder and broke his neck.

At the castle of Liebenstein, a mother sold her child for this purpose. As the wall rose about the little one it cried out: "Mother, I still see you!" then later, "Mother, I can hardly see you!" and lastly, "Mother, I see you no more!" 124b Several other castles have similarly ghastly stories connected

with them. The latest authentic instance of the actual immuring of a human victim alive, occurred at Algiers, when Geronimo of Oran was walled up in the gate Bab-el-Oved in 1569.

Most so-called Devil's Bridges have some story associated with them, keeping alive the old idea of sacrifice, though sometimes substituting an animal for a human victim. The most usual account is that the devil had promised his aid on condition of having the first life that passed over the bridge, and then follow the dodges by which he was cheated, showing that his wits were not estimated much higher than those of the Giant in Jack the Giant-Killer.

In all ages it has been customary in sacrifice to substitute a victim of less value for one of more importance. The same idea, as that involved in the substitution of the sham for the real in the offerings made to the dead, is found running through sacrifice. This latter is defined as "primarily a meal offered to the deity," 125 and the offering up of a human victim has been in all ages considered the highest and most important.

The Romans substituted puppets for the human sacrifices to the goddess Mania. They threw rush dolls into the Tiber at the yearly atoning sacrifice on the Sublician Bridge. How curiously this corresponds with a find here in Devon! A few years ago the north wall of Chumleigh Church was pulled down, and there, in it, was found a carved crucifix, of a date much earlier than the Perpendicular wall of the fifteenth century, when this figure was built into it as a substitute. Not far off, at Holsworthy, at about the same time, as we have just

noted, the church wall was built upon a veritably living victim. Was Chumleigh more advanced in civilisation in the fifteenth century, or less devout in its belief in the efficacy of real sacrifice? or were the Holsworthy people less chary of human life, and, equally believing in the value of the rite, determined to fulfil it to the ideal, so as to ensure a good result?

Substitution in sacrifice, however, was of much earlier date than either Chumleigh or Roman offerings. The Egyptians who put off their dead with counterfeits, offered an animal to their gods instead of a man, but they symbolised their intended act by marking the creature to be slain with a seal bearing the image of a man bound and kneeling, with a sword at his throat. 125a

When once the notion of substitution has got in, whether in offerings to gods or men, the decadence becomes rapid, and in these latter days takes the form of buttons and base counters in our offertory bags.

In modern Greece at the present day it is still customary to consecrate the foundation of a new building with the sacrifice of some bird or animal; but sometimes, perhaps on a great occasion, upon which in old times a human victim would have been offered, the builder who cannot do this, typifies it by building on a man's shadow. He entices a man on to the site, secretly measures his body or his shadow, and buries the measure under the foundation stone. It is believed, too, in this case that the man whose shadow is thus buried will die within the year. 126

The Roumanians have a similar custom, and they,

too, believe that he of the buried shadow will die within the year; it is therefore common to cry out to persons passing a newly begun building: "Beware lest they take thy shadow!" Not long since all this was thought necessary for securing stability to the walls, and there were actually people whose trade it was to supply architects with shadows.

Our own very commonly uttered sentiment, "May your shadow never grow less!" is at least a coincidence.

From the shadow the step is but very short to the reflection, consequently we find many savage people who regard their likeness in a mirror as their soul. The Andaman and Fiji Islanders, with others, hold this belief, and of course its corollary, that injury to the reflection is equivalent to injury to the shadow, and so to the person reflected.

Far away from these islanders, it was believed that the reflection may be stabbed as much as the shadow. One method among the Aztecs of keeping away sorcerers was to leave a bowl of water with a knife in it behind the door. A sorcerer entering would be so alarmed at seeing his likeness transfixed by a knife, that he would instantly turn and flee.

Surely here we have in this very ancient and widespread belief, the basis of that very common one amongst our own enlightened selves, of the terrible calamity which awaits the person who destroys his own image by breaking a looking-glass. Some hold that "he will shortly lose his best friend," which may of course mean that he will die himself, others that it portends speedy mortality in the family, usually the master. 127

In Germany, England, 128 Scotland, and other places even as far off as India and Madagascar, it is still believed that, if after death a person see his image reflected in a mirror in the same room as the dead, he will shortly die himself; hence in many places it is customary to cover up looking-glasses in a death-chamber. Bombay Sunis not only cover the looking-glasses in the room of a dying person, but do so habitually in their bedrooms before retiring to rest. 129

The Zulus and Basutos of South Africa have almost precisely similar notions. We have no need however to go so far afield for instances of a belief of a similar kind.

The following story is given by a correspondent of the Spectator, of February 17, 1894, as told to him "last month" by an old woman, in a Somerset village about ten miles from Bristol.

"Old John, that do live out to Knowle Hill, have a-told I, his vaether George had a sister, an' when her wer' young, a man what lived next door come a-courten of she. But she wouldn't have none on him. But she were took bad, an' had a ravennen appetite, an' did use to eat a whole loaf at once. Zoo her brother thought she wer' overlooked; an' he went down to Somerton, where a man did bide who wer' a real witch, and zo zoon as George got to un, he did zay: 'I do knaw what thee bist a-cwome var; thy zister be overlooked by the neighbour as do live next door. I'll tell 'ee what to do, an' 'twont cost thee no mwore than a penny.' Zoo her told un to goo whoam an' goo to the blacksmith an' get a new nail, an' not to let thick nail out of her hand till her'd a-zeed un make a track, then her were to take an' nail down the track. Zoo George did as her wer' twold, an' when her zeed the man make a track, her took the nail in one hand an' the hammer in t'other, an' a-nailed down the track. And the man did goo limping vrom

that time, and George's sister she got well. Zome time arter that, the man wer' took very bad, an' George's wife did work vor a leädy, an' she twold her missus he wer' ill. Zoo her missus gied her a rhabbut to teäke to the man, but when she got to his house some men outzide the door twold her he wer' dead. Then she did offer to goo an' help lay un out, and wash un, because she wanted to look wether or no there wer' anything wi' his voot. Zo she went and helped lay un out, an' zhure enough there wer' a place right under his voot, as if so be a nail had been hammered into un. An' this, John her son twold I as it were certain true." 129a

The strange notion, that the soul goes out of the body with the shadow or the reflection, is carried still further by many savage people, and obstinately remains with some civilised ones, who think it unlucky to be photographed or to have their portraits painted. They have a fancy that it will shorten their days, just as many have about insuring their lives. This idea is the secret of the savage's unwillingness to be photographed, or to have his likeness sketched, which may be said to be almost universal.

A recent traveller 130 gives a graphic account of his experience among the Ainus after having apparently in another place (Volcano Bay) been permitted to paint the people unmolested, except by inquisitiveness. He says that a young lad came over to see what he was doing, and that being told the author was painting a group of his people, "the news seemed to give him a shock. . . . He rejoined the others, excitedly muttered some words, and apparently told them that I had painted the whole group, fish and all. Had any one among them been struck by lightning, they certainly could not have

looked more dismayed. . . . The fish was thrown aside, but not the knives, armed with which they all rushed at my back." He describes how his paint-box and apparatus were smashed, the painting destroyed, and he himself knocked down and "a big knife was kept well over my head."

The dread of being pictured is found all over the world. The writer has often heard Somerset people object to having their likenesses taken on the ground that it is unlucky, and that so and so was "a-tookt," but soon afterwards she was "took bad and died." Of course these persons would indignantly repudiate any suggestion of superstition; indeed they would do the same about any other belief, such as the death-watch, or an owl's hooting, nevertheless they confess to the feeling and are strongly influenced by it. Quite recently the wife of a gardener near the writer's home objected to have her photograph taken upon the ground that she had "a-yeard 'twas terrible onlucky"; and that "volks never didn live long arter they be a-tookt off," i.e. photographed.

Whence then do these notions come, if they are not the heritage of untold ages?

44:63 Tylor, Primitive Culture, vol. i. p. 101.

45:64 R. Stuart Poole in Smith's Dict. of Bible, s.v. "Magic."

46:65 1 Samuel xxviii. 7 et seq.

46:66 Tylor, Primitive Culture, vol. i. p. 101.

46:67 Spectator, July 14, 1894, p. 45.

47:68 "Mediæval Records," Spectator, January 6, 1894, p. 14.

47:69 These remarks are suggested by a "scientific gentleman," who was a witness with the writer of the twisting of the rod above mentioned, and who had the taste to assert that the young lady was in league with the Dowser.

47:70 Since this was written we have been favoured with Mr. Huxley's ex cathedra deliverance in the Times of July 9, 1894, on Mr. Lang's book, Cock Lane and Common Sense, which may be shortly summed up: "I do not understand these things, therefore they are not."

No doubt superior people would nowadays accept the consequence, which John Wesley put so plainly when he said "to give up belief in witchcraft was to give up the Bible" (Farrar. Smith's Dict. of Bible, s.v. "Divination," 101. i. p. 445). We, however, venture to believe that there is a middle course, that of determining what we mean by witchcraft. As vulgarly understood and practised we are of course uncompromising unbelievers.

48:71 Tylor, Primitive Culture, vol. i. p. 104.

48:72 Frazer, Golden Bough, vol. i. p. 9.

49:73 Frazer, Golden Bough, vol. i. p. 9.

49:74 In the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford, is the original clay figure actually made to represent a man, whose death it was intended thereby to compass. This happened no longer ago than 1889 in Glen Urquhart, where the image was placed before the house of an inhabitant. That this is not an uncommon act is proved by their having in Gaelic a distinct name for the clay figure--Corp Creidh, the clay body, well understood to mean the object and purpose above described. The great antiquity of this mode of working evil is shown by the discovery at Thebes of a small clay figure of a man tied to a papyrus scroll, evidently to compass the destruction of the person represented and denounced in the scrip. This figure and papyrus are now in the Ashmolean Museum. We refer again to this subject in Chapter XI.

49:75 Wilkinson, Anc. Egypt, vol. iii. p. 492.

50:76 Maspero, Archæol. Egyp. p. 245. Of the ancient Greeks, we are told that in some "places they placed their infants in a thing bearing some resemblance to whatever sort of life they designed them for. Nothing was more common than to put them in vans, or conveniences to winnow corn, which were designed as omens of their future riches and affluence" (Potter, Archæol. Græc. vol. ii. p. 321). We are further told these "things" were not real but imitations.

50:76a Fig. 1 is from Wilkinson, Anc. Egyp. Figs. 2 and 3 from author's collection.

51:77 "C'étaient des simulacres de pains, d'offrandes destinés à nourrir le mort éternellement. Beaucoup de vases qu'on déposait dans le tombe sont peints en imitation d'albâtre, de granit, de basalte, de bronze ou même d'or, et sont le contrfaçon à bon marché des vases en matières précieuses, que les riches donnaient aux momies."--Maspero, Archæol Egyp. p. 245. Upon this subject see also Maspero, Histoire Ancienne des peuples de l'Orient, p. 53 sq.; Ib. Trans. Bibl. Archæol. Soc. vol. vii. p. 6 sq.; Mariette, Sur les Tombes de l'Ancien Empire, p. 17 sq.; Brugsh, Die Ægyptische Gräberwelt, p. 16. sq.

52:78 Maspero, Études Égyptiennes, vol. i. p. 192. See also Mariette, Sur les Tombes, p. 8. Closely allied to this is the breaking of votive offerings to SS. Cosmo and Damian, referred to later.

53:79 Fig. 4 was found October 1882 in a recess of a chimney in an old house occupied by Mrs. Cottrell in the village of Ashbrittle. It was wrapped in a flannel bag, black and rotten, which crumbled to pieces. Some of the old people declared it to have been a custom when a pig died from the "overlooking" of a witch to have its heart stuck full of pins and white thorns, and to put it up the chimney, in the belief that as the heart dried and withered so would that of the malignant person who bad "ill wisht" the pig. As long as that lasted no witch could have power over the pigs belonging to that house. Fig. 5 was found nailed up inside the "clavel" in the chimney of an old house at Staplegrove in 1890. One side of this heart is stuck thickly with pins, the other side, here shown, has only the letters M. D. which are considered to be the initials of the supposed witch.

54:80 Herbert Ward, Five Years with the Congo Cannibals, 1890.

Only ten years ago an old woman died here in the Workhouse, who was always a noted witch. She was the terror of her native village (in the Wellington Union), as it was fully believed she could "work harm" to her neighbours. Her daughter also, and others of her family, enjoyed the like reputation. Virago-like she knew and practised on the fears of the other inmates of "the House." On one occasion she muttered a threat to the matron, that she would "put a pin in for her." The other women heard it, and cautioned the matron not to cross her, as she had vowed to put in a pin for her, and she would do it. When the woman died there was found fastened to her stays a heart-shaped pad stuck with pins; and also fastened to her stays were four little bags in which were dried toads' feet. All these things rested on her chest over her heart, when the stays were worn.

A farm boy left his employment in a neighbouring parish against his p. 55 master's wish, "to better himself," and took service near. Soon after, he was seized with a "terrible" pain in his foot, so that he could neither stand nor drive home the cows. An acquaintance coming by took him home in his cart, and advised him to consult "Conjurer ------." The latter told him at once, "Somebody's workin' harm 'pon thee." In the end the boy was advised to go back to his old place, and to keep a sharp watch if Mr. or Mrs. ------ took anything down out of the "chimbly." "’Nif they do, and tear'n abroad, they can't never hurt thee no more." After many questions he was taken back into the house again, and in a short time he saw Mrs. ------ take an image down from the chimney. "’was a mommet thing, and he knowd 'twas a-made vor he." He saw that the feet of the little figure were stuck full of pins and thorns! As soon as he found out that the thing was destroyed, he went off again to farmer ------'s, because his feet got well directly, and he knew they could not work harm a second time.

Fifteen years ago, at a town in Devonshire, lived for many years an unmarried woman, the mother of several children. The woman left, and a neighbour searching about the house found, in the chimney as usual, onions stuck thickly with pins, and also a figure made unmistakably to represent das mannliche Glied, into which also were stuck a large number of pins. The people who crowded to see these things had no doubt whatever as to their being intended for a certain man who kept a little shop near, and had been known as a visitor of this woman, who thus vented her spite upon him.

The names of the parties to all these stories are known to me, and the "Conjurer" up to his death a few years ago occupied a cottage belonging to my father.

The pins in an onion are believed to cause internal pains, and those in the feet or other members are to injure the parts represented, while pins in the heart are intended to work fatally; thus a distinct gradation of enmity can be gratified.

55:81 Letter from Mr. J. L. W. Page (Author of Explorations of Dartmoor, Exmoor, etc.), October 20, 1890.

56:82 W. F. Rose, Somerset and Dorset Notes and Queries, vol. iv. part xxvi. p. 77 (1894).

56:83 Those whose profession is to counter-charm and to discover witchcraft are white witches or "wise men," or more commonly "conjurers." They are usually, but not always, men.

56:84 H. S. in the Spectator, Feb. 17, 1894, p. 232.

In all the foregoing instances, it will be noted that the hearts or onions were to be scorched either by being actually thrown on the fire or by being placed in the chimney, where they would be exposed to much heat. The inside of the clavel beam would be a particularly hot place. A specimen of the same kind of heart as Fig. 5, at Oxford (Pitt Rivers Museum), has also a large nail through it, to fasten it to the wooden clavel.

57:85 Mrs. Gaskell in Nineteenth Century, Feb. 1894, p. 264.

This, however, is somewhat wide of our subject, and belongs rather to the widely-extended belief in holy wells and sacred springs. (For full information on this subject, see Mackinlay, Folk Lore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, 1894.)

58:86 In the same case are to be seen one or two other hearts of the same character as Figs. 4 and 5, though less perfect as specimens.

58:87 Petronius, Sat. 131. Story, Castle of S. Angelo, p. 211. Jahn, etc., p. 42, says: "Bunte Fäden spielten bei allen Zauberwesen eine grosse Rolle," and gives numerous references to classics and scholiasts.

59:88 Persius, Sat. ii. 31. There is also a very common practice both in England and elsewhere of tying a bunch of many-coloured ribbons to horses' heads. "During the panic caused in Tunis by the cholera some extraordinary remedies were eagerly run after by the populace." Among others one woman "sold bits of coloured ribbon to be pinned on the clothes of those who were anxious to escape the epidemic" (Hygiene, Nov. 17, 1893, p. 938).

59:89 On this subject see Sacred Wells in Wales, by Professor Rhys, read before the Cwmrodorian Society, January 11, 1893.

60:90 Compare this with the many examples of sending away various diseases by hanging articles on trees, giver, by Dr. Tylor, Primitive Culture, vol. ii. p. 137.

61:91 The True Preserver and Restorer of Health, by G. Hartman, Chymist, 1695, servant of Sir Kenelm Digby.

62:92 See "Crying the Neck," Transactions Devon Association, 1891.

63:93 At the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, are many specimens of this Harvest figure from several parts of the world. Particularly several "Kirn babies" from Scotland, made from the last of the corn cut, and thus supposed to contain the corn spirit. Though not precisely alike in form, they are exactly analogous in motive to the "Neck" of Devon and West Somerset. Upon "Kirn babies," Brand fell into the error that Kirn meant corn, from similarity of sound. The word really means churn, and is precisely analogous to kirk and church. At harvest time in Scotland there has always been a great churning of butter for the festival, and hence the Kirn has developed into the name for the festival itself. Baby is but the old English name for a doll or "image," as Brand recognised. Therefore the Kirn baby has nothing to do with the word corn, but means a "Harvest-festival doll." Theories built up upon its meaning corn-maiden, are without any foundation except that of connection with the end of harvest. No doubt these figures are made from the last of the corn, and do represent the spirit of vegetation, but their signification is by no means implied in their Scotch name. Mr. Frazer (Golden Bough, vol. i. p. 344) has therefore been misled by Brand. See N. E. Dict. s.v. "Corn-Baby."

63:94 See Brand, vol. i. p. 226 et seq.

63:95 Elton, Origins of English History, 2nd ed. p. 282.

64:96 Martin, Description of Western Islands, quoted by Elton, Orig. p. 282.

64:97 In ancient Greece, "on the fifth day after the birth, the midwives, having first purified themselves by washing their hands, ran round the fire hearth with the infant in their arms, thereby, as it were, entering it into the family" (Potter, Archæol. Græc. vol. ii. p. 322).

64:98 Rhys, Welsh Philology, p. 10.

64:99 Kemble, Saxons in England, vol. i. p. 360, has a long note on this act in Perthshire during the present century, and also in Devonshire.

64:100 We refer to these fires later on, but they were undoubtedly relics of sun-worship.

"In Munster and Connaught a bone (probably the representative of the former sacrifice) must be burnt in them (Baal fires). In many places sterile beasts and human beings are passed through the fire. As a boy I with others jumped through the fire 'for luck,' none of us knowing the original reason. "--Kinahan, Folk-Lore Record, vol. iv. 1881, quoted Notes and Queries, 8th ser. v. 433.

65:101 Elton, Origins of English History, p. 276.

65:102 Tylor, Primitive Culture, vol. ii. p. 387.

66:103 Selden says: "’Tis in the main allowed that the heathens did in general look towards the east when they prayed, even from the earliest ages of the world."

66:104 Potter, vol. i. pp. 223, 224. Upon the subject of "Bowing towards the Altar" much is said in Brand, vol. ii. pp. 317-324 (Bohn, 1882).

67:105 Lumboltz, Among Cannibals, 1889, p. 276.

67:106 Brugsch, Egypt under the Pharaohs, vol. ii. p. 412, 2nd ed. 1881,

67:107 The facts given here are those observed, and those related on the spot traditionally. It is however clear that although this temple may have been truly orientated by Rameses for the day of his great battle, yet that date could not then have corresponded with the present season of February 24, owing to the precession of the equinox. Upon this subject see Norman Lockyer in The Dawn of Astronomy, reviewed in the Times, February 2, 1894.

68:108 As we proceed we shall see other striking examples of this eclecticism of modern Christianity, and a lesson of tolerance may well be learnt from the spectacle.

69:109 Potter, vol. i. pp. 224, 261.

69:110 Ibid. vol. i. pp. 262, 263.

70:111 Mead, Proceed. Som. Arch. and Nat. Hist. Soc. vol. xxxviii. p. 362, 1892. Also F. T. Elworthy in Spectator, February 5, 1887. The tree itself about which this notice in the Spectator was written is now in the Somerset Archæological Society's Museum at Taunton.

70:112 First Report of Committee on Ethnographical Survey of the United Kingdom (Sec. H, British Association), 1893, p. 15.

70:113 Potter, vol. i. p. 265.

72:114 D. Porter, Journal of a Cruise in the Pacific, vol. ii. p. 188. Dawson, Australian Aborigines, tells other stories of this nature.

Frazer, Golden Bough, vol. i. p. 198, gives many references to authors who have recounted instances of this common belief.

73:115 Dawson, Australian Aborigines, p. 54.

73:116 Here we have another link in that remarkable chain of beliefs so ably demonstrated by Dr. Tylor, at the British Association meeting, 1894, in his lecture on the "Distribution of Mythical Beliefs as evidence in the History of Culture," which seems also to prove the common parentage of widely-separated races. The ultimate relationship of the Nagas of Assam, with the Australian aborigines, through migration by way of Formosa, Sumatra, and the Indian Archipelago, is traced by Mr. Peal in "Fading Histories," Journ. Asiatic Soc. of Bengal, lxiii. part iii. No. 1, 1894.

73:117 Lumholtz, Among Cannibals, 1889, p. 280.

77:118 Prof. Rhys, "Welsh Fairies," art. in Nineteenth Century, Oct. 1891, p. 566. Cf. also remark on Herbert River natives, p. 73.

77:119 Jorio, Mimica degli Antichi, p. 92.

78:120 Lumholtz, Among Cannibals, p. 279.

78:121 Bastian, Die Völker des östlichen Asien, v. 455.

78:122 Torreblanca, De Magia, ii. 49.

79:123 Tylor, Primitive Culture, vol. i. p. 94 et seq. gives a number of very remarkable instances of foundation sacrifices from all parts of the world as for instance, quite in modern times even in our own possessions in the Punjaub--the only son of a widow was thus sacrificed. But perhaps the strangest account of all is that of several willing victims, making the story of Quintus Curtius seem quite commonplace.

79:124 Baring-Gould, art. "On Foundations," in Murray's Magazine, March 1887, pp. 365, 367. Tylor tells the same story, op. cit. i. 94.

79:124a These stories are sifted and disproved in The Immuring of Nuns, by the Rev. H. Thurston, S.J., Catholic Truth Society, 1st ser. p. 125; but he by no means controverts facts relating to long antecedent beliefs.

80:124b For authorities see Note 124, p. 79.

81:125 Robertson Smith, art. "Sacrifice," in Ency. Brit.

82:125a Robertson Smith, art. "Sacrifice," in Ency. Brit.

82:126 Schmidt, Das Volksleben der Neugriechen, p. 196 et seq. Frazer, Golden Bough, vol. i. p. 145, also quotes as above, and gives many other authorities, See also Baring-Gould, Murray's Magazine, March 1887, p. 373.

83:127 Dyer, English Folk Lore, p. 277.

84:128 Dyer, English Folk Lore, p. 109. Folk-Lore Journal, vol. iii. p. 281.

84:129 Punjaub Notes and Queries, vol. ii. p. 906, quoted by Frazer.

85:129a The recorder of this story doubtless gives the facts correctly; but his rendering of the dialect is quite literary.

85:130 A. H. S. Landor, Alone with the Hairy Ainu, p. 13