Sacred Texts Earth Mysteries Index Previous Next

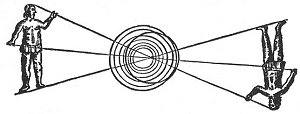

BELOW IS A GROUP OF EIGHT FIGURES whose whole interest lies just in their association. With their science we have nothing to do here, since they are old attempts, most of them, to account for the observed aberrations of movement among the heavenly bodies. Wang Ch’ung, an old Chinese philosopher, expressed a part of this still unsolved problem very oddly and simply indeed. Writing of the complex movements of the Sun and the Moon in relation to the heavens, he said: That Heaven turns sideways to the left "like a millstone"; that the Sun and Moon move to the right, but are swept by Heaven to the left; that their real movement is towards the east, but they are carried by Heaven towards the west, where they "go down"; that they resemble ants creeping to the left side on a millstone turning to the right, but that the millstone, being much swifter than the ants, compels them to follow it to the right.

Old astronomers, however, employed two devices to aid them in their calculations; one to account for the seeming difference observed in the speed of the Sun's movement in its orbit; the other to account for the seeming alternation of direction in the movements of the planets.

The Sun, for instance, when describing a certain segment

Click to enlarge

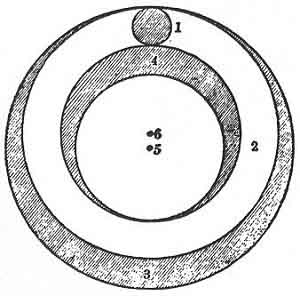

PLATE XXXIX. Kepler's diagram of The Law connecting the relative distances of the planets.

of its orbit, travelled at a greater speed--or so it seemed--than when it moved in the corresponding opposite quarter. To the Sun, therefore, was given a place in the heavens called the Excentric sphere--it was another theory of two centres. For it was assumed that all the

FIGURE 93. The excentric sphere of Mahmud ibn Muhammed ibn Omar al Jagmini (c. 13th century A.D.)

1. The Sun. 2. Excentric sphere. 3. Surrounding sphere. 4. Complement of the surrounding sphere. 5. Centre of the world. 6. Centre of the excentric sphere.

(From The History of the Planetary Systems from Thales to Kepler; J. L. E. Dreyer, 1906.)

heavenly spheres were not concentric, did not, that is, have the Earth's centre as a common centre; and that the centre of one sphere of revolution might be a point a little removed from the centre of the Earth. According to this theory, when the Sun was near the Earth, its speed would appear much greater than when it was moving at a distance farther away.

Click to enlarge

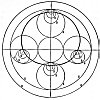

FIGURE 94. The ''Guiding Spheres'' of Nasir-Eddin Attûsi

(13th century A.D.)

(From The History of the Planetary Systems from Thales to Kepler; J. L. E. Dreyer, 1906, pp. 269-270.)

(2) and (4) and (5) revolve in the same period, that in which the centre of the epicycle performs a revolution; (3) revolves in half that time, while (6) revolves in the opposite direction with the same speed as the apogee of the excentric.

The figure now shows how the epicycle moves to and fro along the diameter of (4), and during the revolution of the circle (5) describes a closed curve, about which Nasir-Eddin justly says that it is somewhat like a circle but is not really one, for which reason it is not a perfect substitute for the excentric circle of Ptolemy.

To account for the seeming alternation of direction in the movements of the planets, the theory of the Epicycle was evolved. This meant, briefly, that a planet did not

Click to enlarge

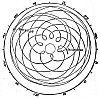

FIGURE 95. The movement described by Mars, 1580-1596.

(From Astronomia Nova; Johann Kepler, 1609.)

move directly in the circumference of its revolving sphere or cycle--as, for instance, the Sun moved in its excentric sphere, but in an epicycle or small circle that revolved around a fixed point in the larger circle and carried the

planet with it; "fixed to its inner surface," says an old Arabian astronomer, "like a pearl on a ring, touching the surface in one point." For a time these devices of the excentric and the epicycle seemed to work fairly well;

Click to enlarge

FIGURE 96. Theory of three centres and the movement of Venus.

M. Centre of the world. E. Centre of the excentric. S. Centre of the equant. The centre of the star-bearing circle at the top is the centre of the epicycle.

(From Theoricæ Novæ; Georg Peurbach, 1581.)

but after a while the astronomers found themselves entangled in such a maze of centrics and excentrics, cycles and epicycles, and spheres heaped upon spheres, that they never found their way out of the labyrinth they had themselves constructed, and eventually the system that was to

account for all the mysteries of the heavenly movements fell of itself.

Dante's favorite description of the heavens was "wheels upon wheels," and Jagmini's diagram (Fig. 93) shows the "excentric wheel" of the Sun, itself a solid spherical body the edges of whose wheel touch two other surfaces, in the common centre of which is the Earth. But the centre of

FIGURE 97. The relation of the harmony of the Microcosmos to the Macrocosmos.

(From Microcosmi Historia; Robert Fludd, 1621.)

the excentric sphere is not "the centre of the world." For there were "pulls" in the heavens that resulted in constantly shifting centres. Nasir-Eddin Attûsi, great Arabian astronomer of Jagmini's century, attempted to account for the various lunacies of the heavens by, literally, "the spots on the moon." These spots, he assumed, are caused by other bodies moving in its epicycle and un-equally exposed to its light, and this phenomenon he calls "the anomaly of illumination." The movements of the five planets, particularly those of Mercury and Venus, required, he said, "the introducing of a system of guiding spheres," and this theory, when fully worked out (Fig. 94)

gave him, for the path of Mercury, not the excentric circle of Ptolemy, nor a circle at all, but a curious closed curve

FIGURE 98. The Balance.

(From Mundus Subterraneus; Athanasius Kircher, 1678, Vol. II.)

with unequal radii which he described as "somewhat like a circle, but not really one."