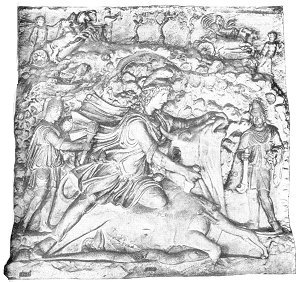

KING ANTIOCHUS AND MITHRA.

(Bas-relief of the colossal temple built by Antiochus I. of Commagene, 69-31 B.C., on the Nemrood Dagh, a spur of the Taurus Mountains. T. et M., p. 188.)

IN THAT unknown epoch when the ancestors of the Persians were still united with those of the Hindus, they were already worshippers of Mithra. The hymns of the Vedas celebrated his name, as did those of the Avesta, and despite the differences obtaining between the two theological systems of which these books were the expression, the Vedic Mitra and the Iranian Mithra have preserved so many traits of resemblance that it is impossible to entertain any doubt concerning their common origin. Both religions saw in him a god of light, invoked together with Heaven, bearing in the one case the name of Varuna and in the other that of Ahura; in ethics he was recognized as the protector of truth, the antagonist of falsehood and error. But the sacred poetry of India has preserved of him an obscured memory only. A single fragment, and even that partially effaced, is all that has been specially dedicated to him. He appears mainly in incidental allusions,--the silent witnesses of his ancient grandeur. Still, though his physiognomy is not so distinctly

limned in the Sanskrit literature as it is in the Zend writings, the faintness of its outlines is not sufficient to disguise the primitive identity of his character.

According to a recent theory, this god, with whom the peoples of Europe were unacquainted, was not a member of the ancient Aryan pantheon. Mitra-Varuna, and the five other Adityas celebrated by the Vedas, likewise Mithra-Ahura and the Amshaspands, who, according to the Avestan conception surround the Creator, are on this theory nothing but the sun, the moon, and the planets, the worship of which was adopted by the Indo-Iranians "from a neighboring people, their superiors in the knowledge of the starry firmament," who could be none other than the Accadian or Semitic inhabitants of Babylonia. 1 But this hypothetical adoption, if it really took place, must have occurred in a prehistoric epoch, and, without attempting to dissipate the obscurity of these primitive times, it will be sufficient for us to state that the tribes of Iran never ceased to worship Mithra from their first assumption of worldly power till the day of their conversion to Islam.

In the Avesta, Mithra is the genius of the celestial light. He appears before sunrise on the rocky summits of the mountains; during the day he traverses the wide firmament in his chariot drawn by four white horses, and when

night falls he still illumines with flickering glow the surface of the earth, "ever waking, ever watchful." He is neither sun, nor moon, nor stars, but with "his hundred ears and his hundred eyes" watches constantly the world. Mithra hears all, sees all, knows all: none can deceive him. By a natural transition he became for ethics the god of truth and integrity, the one that was invoked in solemn oaths, that pledged the fulfilment of contracts, that punished perjurers.

The light that dissipates darkness restores happiness and life on earth; the heat that accompanies it fecundates nature. Mithra is "the lord of wide pastures," the one that renders them fertile. "He giveth increase, he giveth abundance, he giveth cattle, he giveth progeny and life." He scatters the waters of the heavens and causes the plants to spring forth from the ground; on them that honor him, he bestows health of body, abundance of riches, and talented posterity. For he is the dispenser not only of material blessings but of spiritual advantages as well. His is the beneficent genius that accords peace of conscience, wisdom, and honor along with prosperity, and causes harmony to reign among all his votaries. The devas, who inhabit the places of darkness, disseminate on earth along with barrenness and suffering all manner of vice and impurity. Mithra, "wakeful and sleepless, protects the creation of Mazda" against

their machinations. He combats unceasingly the spirits of evil; and the iniquitous that serve them feel also the terrible visitations of his wrath. From his celestial eyrie he spies out his enemies; armed in fullest panoply he swoops down upon them, scatters and slaughters them. He desolates and lays waste the homes of the wicked, he annihilates the tribes and the nations that are hostile to him. On the other hand he is the puissant ally of the faithful in their warlike expeditions. The blows of their enemies "miss their mark, for Mithra, sore incensed, receives them"; and he assures victory unto them that "have had fit instruction in the Good, that honor him and offer him the sacrificial libations." 1

This character of god of hosts, which has been the predominating trait of Mithra from the days of the Achæmenides, undoubtedly became accentuated in the period of confusion during which the Iranian tribes were still at war with one another; but it is after all only the development of the ancient conception of struggle between day and night. In general, the picture that the Avesta offers us of the old Aryan deity, is, as we have already said, similar to that which the Vedas have drawn in less marked outlines, and it hence follows that Mazdaism left its main primitive foundation unaltered.

Still, though the Avestan hymns furnish the

distinctest glimpses of the true physiognomy of the ancient god of light, the Zoroastrian system, in adopting his worship, has singularly lessened his importance. As the price of his admission to the Avestan Heaven, he was compelled to submit to its laws. Theology had placed Ahura-Mazda on the pinnacle of the celestial hierarchy, and thenceforward it could recognize none as his peer. Mithra was not even made one of the six Amshaspands that aided the Supreme Deity in governing the universe. He was relegated, with the majority of the ancient divinities of nature, to the host of lesser genii or yazatas created by Mazda. He was associated with some of the deified abstractions which the Persians had learned to worship. As protector of warriors, he received for his companion, Verethraghna, or Victory; as the defender of the truth, he was associated with the pious Sraosha, or Obedience to divine law, with Rashnu, Justice, with Arshtât, Rectitude. As the tutelar genius of prosperity, he is invoked with Ashi-Vañuhi, Riches, and with Pâreñdî, Abundance. In company with Sraosha and Rashnu, he protects the soul of the just against the demons that seek to drag it down to Hell, and under their guardianship it soars aloft to Paradise. This Iranian belief gave birth to the doctrine of redemption by Mithra, which we find developed in the Occident.

At the same time, his cult was subjected to

a rigorous ceremonial, conforming to the Mazdean liturgy. Sacrificial offerings were made to him of "small cattle and large, and of flying birds." These immolations were preceded or accompanied with the usual libations of the juice of Haoma, and with the recitation of ritual prayers,--the bundle of sacred twigs (baresman) always in the hand. But before daring to approach the altar, the votary was obliged to purify himself by repeated ablutions and flagellations. These rigorous prescriptions recall the rite of baptism and the corporeal tests imposed on the Roman neophytes before initiation.

Mithra, thus, was adopted in the theological system of Zoroastrianism; a convenient place was assigned to him in the divine hierarchy; he was associated with companions of unimpeachable orthodoxy; homage was rendered to him on the same footing with the other genii. But his puissant personality had not bent lightly to the rigorous restrictions that had been imposed upon him, and there are to be found in the sacred text vestiges of a more ancient conception, according to which he occupied in the Iranian pantheon a much more elevated position. Several times he is invoked in company with Ahura: the two gods form a pair, for the light of Heaven and Heaven itself are in their nature inseparable. Furthermore, if it is said that Ahura created Mithra as he did all things, it is likewise said

that he made him just as great and worthy as himself. Mithra is indeed a yazata, but he is also the most potent and most glorious of the yazata. "Ahura-Mazda established him to maintain and watch over all this moving world." 1 It is through the agency of this ever-victorious warrior that the Supreme Being destroys the demons and causes even the Spirit of Evil, Ahriman himself, to tremble.

Compare these texts with the celebrated passage in which Plutarch 2 expounds the dualistic doctrine of the Persians: Oromazes dwells in the domain of eternal light "as far above the sun as the sun is distant from the earth"; Ahriman reigns in the realm of darkness, and Mithra occupies an intermediary place between them. The beginning of the Bundahish 3 expounds a quite similar theory, save that in place of Mithra it is the air (Vayu) that is placed between Ormazd and Ahriman. The contradiction is only one of terms, for according to Iranian ideas the air is indissolubly conjoined with the light, which it is thought to support. In fine, a supreme god, enthroned in the empyrean above the stars, where a perpetual serenity exists; below him an active deity, his emissary and chief of the celestial armies in their ceaseless combat

with the Spirit of Darkness, who from the bowels of Hell sends forth his devas to the surface of the earth,--this is the religious conception, far simpler than that of Zoroastrianism, which appears to have been generally accepted among the subjects of the Achæmenides.

The conspicuous rôle that the religion of the ancient Persians accorded to Mithra is attested by a multitude of proofs. He alone, with the goddess Anâhita, is invoked in the inscriptions of Artaxerxes alongside of Ahura-Mazda. The "great kings" were certainly very closely attached to him, and looked upon him as their special protector. It is he whom they call to bear witness to the truth of their words, and whom they invoke on the eve of battle. They unquestionably regarded him as the god that brought victory to monarchs; he it was, they thought, who caused that mysterious light to descend upon them which, according to the Mazdean belief, is a guaranty of perpetual success to princes, whose authority it consecrates.

The nobility followed the example of the sovereign. The great number of theophorous, or god-bearing, names, compounded with that of Mithra, which were borne by their members from remotest antiquity, is proof of the fact that the reverence for this god was general among them.

Mithra occupied a large place in the official cult. In the calendar the seventh month was

dedicated to him and also doubtless the sixteenth day of each month. At the time of his festival, the king, if we may believe Ctesias, 1 was permitted to indulge in copious libations in his honor and to execute the sacred dances. Certainly this festival was the occasion of solemn sacrifices and stately ceremonies. The Mithrakana were famed throughout all Hither Asia, and in their form Mihragân were destined, in modern times, to be celebrated at the commencement of winter by Mussulman Persia. The fame of Mithra extended to the borders of the Ægean Sea; he is the only Iranian god whose name was popular in ancient Greece, and this fact alone proves how deeply he was venerated by the nations of the great neighboring empire.

The religion observed by the monarch and by the entire aristocracy that aided him in governing his vast territories could not possibly remain confined to a few provinces of his empire. We know that Artaxerxes Ochus had caused statues of the goddess Anâhita to be erected in his different capitals, at Babylon, Damascus, and Sardis, as well as at Susa, Ecbatana, and Persepolis. Babylon, in particular, being the winter residence of the sovereigns, was the seat of a numerous body of official clergy, called Magi, who sat in authority over the indigenous priests. The

prerogatives that the imperial protocol guaranteed to this official clergy could not render them exempt from the influence of the powerful sacerdotal caste that flourished beside them. The erudite and refined theology of the Chaldæans was thus superposed on the primitive Mazdean belief, which was rather a congeries of traditions than a well -established body of definite dogmas. The legends of the two religions were assimilated, their divinities -were identified, and the Semitic worship of the stars (astrolatry), the monstrous fruit of long-continued scientific observations, became amalgamated with the nature-myths of the Iranians. Ahura-Mazda was confounded with Bel, who reigned over the heavens; Anâhita was likened to Ishtar, who presided over the planet Venus; while Mithra became the Sun, Shamash. As Mithra in Persia, so Shamash in Babylon is the god of justice; like him, he also appears in the east, on the summits of mountains, and pursues his daily course across the heavens in a resplendent chariot; like him, finally, he too gives victory to the arms of warriors, and is the protector of kings. The transformation wrought by Semitic theories in the beliefs of the Persians was of so profound a character that, centuries after, in Rome, the original home of Mithra was not infrequently placed on the banks of the Euphrates. According to Ptolemæus, 1 this

potent solar deity was worshipped in all the countries that stretched from India to Assyria.

But Babylon was a step only in the propagation of Mazdaism. Very early the Magi had crossed Mesopotamia and penetrated to the heart of Asia Minor. Even under the first of the Achæmenides, it appears, they established themselves in multitudes in Armenia, where the indigenous religion gradually succumbed to their cult, and also in Cappadocia, where their altars still burned in great numbers in the days of the famous geographer Strabo. They swarmed, at a very remote epoch, into distant Pontus, into Galatia, into Phrygia. In Lydia even, under the reign of the Antonines, their descendants still chanted their barbaric hymns in a sanctuary attributed to Cyrus. These communities, in Cappadocia at least, were destined to survive the triumph of Christianity and to be perpetuated until the fifth century of our era, faithfully transmitting from generation to generation their manners, usages, and modes of worship.

At first blush the fall of the empire of Darius would appear to have been necessarily fatal to these religious colonies, so widely scattered and henceforward to be severed from the country of their birth. But in point of fact it was precisely the contrary that happened, and the Magi found in the Diadochi, the successors of Alexander the Great, no less efficient protection than that which they

enjoyed under the Great King and his satraps. After the dismemberment of the empire of Alexander (323 B.C.), there were established in Pontus, Cappadocia, Armenia, and Commagene, dynasties which the complaisant genealogists of the day feigned to trace back to the Achæmenian kings. Whether these royal houses were of Iranian extraction or not, their supposititious descent nevertheless imposed upon them the obligation of worshipping the gods of their fictitious ancestors. In opposition to the Greek kings of Pergamon and Antioch, they represented the ancient traditions in religion and politics. These princes and the magnates of their entourage took a sort of aristocratic pride in slavishly imitating the ancient masters of Asia. While not evincing outspoken hostility to other religions practised in their domains, they yet reserved especial favors for the temples of the Mazdean divinities. Oromazes (Ahura-Mazda), Omanos (Vohumano), Artagnes (Verethraghna), Anaïtis (Anâhita), and still others received their homage. But Mithra, above all, was the object of their predilection. The monarchs of these nations cherished for him a devotion that was in some measure personal, as the frequency of the name Mithradates in all their families attests. Evidently Mithra had remained for them, as he had been for Artaxerxes and Darius, the god that granted monarchs victory,--the manifestation

and enduring guaranty of their legitimate rights.

This reverence for Persian customs, inherited from legendary ancestors, this idea that piety is the bulwark of the throne and the sole condition of success, is explicitly affirmed in the pompous inscription 1 engraved on the colossal tomb that Antiochus I., Epiphanes, of Commagene (69-34 B.C.), erected on a spur of the mountain-range Taurus, commanding a distant view of the valley of the Euphrates (Figure I). But, being a descendant by his mother of the Seleucidæ of Syria, and supposedly by his father of Darius, son of Hystaspes, the king of Commagene merged the memories of his double origin, and blended together the gods and the rites of the Persians and the Greeks, just as in his own dynasty the name of Antiochus alternated with that of Mithridates.

Similarly in the neighboring countries, the Iranian princes and priests gradually succumbed to the growing power of the Grecian civilization. Under the Achæmenides, all the different nations lying between the Pontus Euxinus and Mount Taurus were suffered by the tolerance of the central authority to practise their local cults, customs, and languages. But in the great confusion caused by the collapse of the Persian empire, all political and

religious barriers were demolished. Heterogeneous races had suddenly come in contact with one another, and as a result Hither Asia passed through a phase of syncretism analogous

KING ANTIOCHUS AND MITHRA.

(Bas-relief of the colossal temple built by Antiochus I. of Commagene, 69-31 B.C., on the Nemrood Dagh, a spur of the Taurus Mountains. T. et M., p. 188.)

to that which is more distinctly observable under the Roman empire. The contact of all the theologies of the Orient and all the philosophies of Greece produced the most startling combinations, and the competition

between the different creeds became exceedingly brisk. Many of the Magi, from Armenia to Phrygia and Lydia, then doubtless departed from their traditional reserve to devote themselves to active propaganda, and like the Jews of the same epoch they succeeded in gathering around them numerous proselytes. Later, when persecuted by the Christian emperors, they were obliged to revert to their quondam exclusiveness, and to relapse into a rigorism that became more and more inaccessible.

It was undoubtedly during the period of moral and religious fermentation provoked by the Macedonian conquest that Mithraism received approximately its definitive form. It was already thoroughly consolidated when it spread throughout the Roman empire. Its dogmas and its liturgic traditions must have been firmly established from the beginning of its diffusion. But unfortunately we are unable to determine precisely either the country or the period of time in which Mazdaism assumed the characteristics that distinguished it in Italy. Our ignorance of the religious movements that agitated the Orient in the Alexandrian epoch, the almost complete absence of direct testimony bearing on the history of the Iranian sects during the first three centuries before our era, are our main obstacles in obtaining certain knowledge of the development of Parseeism. The most we can do is to unravel the principal factors that combined

to transform the religion of the Magi of Asia Minor, and endeavor to show how in different regions varying influences variously altered its original character.

In Armenia, Mazdaism had coalesced with the national beliefs of the country and also with a Semitic element imported from Syria. Mithra remained one of the principal divinities of the syncretic theology that issued from this triple influence. As in the Occident, some saw in Mithra the genius of fire, others identified him with the sun; and fantastic legends were woven about his name. He was said to have sprung from the incestuous intercourse of Ahura-Mazda with his own mother, and again to have been the offspring of a common mortal. We shall refrain from dwelling upon these and other singular myths. Their character is radically different from the dogmas accepted by the Occidental votaries of the Persian god. That peculiar admixture of disparate doctrines which constituted the religion of the Armenians appears to have had no other relationship with Mithraism than that of a partial community of origin.

In the remaining portions of Asia Minor the changes which Mazdaism underwent were far from being as profound as in Armenia. The opposition between the indigenous cults and the religion whose Iranian origin its votaries delighted in recalling, never ceased to be felt. The pure doctrine of which the worshippers

of fire were the guardians could not reconcile itself easily with the orgies celebrated in honor of the lover of Cybele. Nevertheless, during the long centuries that the emigrant Magi lived peacefully among the autochthonous tribes, certain amalgamations of the conceptions of the two races could not help being effected. In Pontus, Mithra is represented on horseback like Men, the lunar god honored throughout the entire peninsula. In other places, he is pictured in broad, slit trousers (anaxyrides), recalling to mind the mutilation of Attis. In Lydia, Mithra-Anâhita became Sabazius-Anaïtis. Other local divinities likewise lent themselves to identification with the powerful yazata. It would appear as if the priests of these uncultured countries had endeavored to make their popular gods the compeers of those whom the princes and nobility worshipped. But we have too little knowledge of the religions of these countries to determine the precise features which they respectively derived from Parseeism or imparted to it. That there was a reciprocal influence we definitely know, but its precise scope we are unable to ascertain. Still, however superficial it may have been, 1 it certainly

Fig. 2.

IMPERIAL COINS OF TRAPEZUS (TREBIZOND), A CITY OF PONTUS.

Representing a divinity on horseback resembling both Men and Mithra, and showing that in Pontus the two were identified.

a. Bronze coins. Obverse: Bust of Alexander Severus, clad in a paludamentum; head crowned with laurel. Reverse: The composite Men-Mithra in Oriental costume, wearing a Phrygian cap, and mounted on a horse that advances toward the right. In front, a flaming altar. On either side, the characteristic Mithraic torches, respectively elevated and reversed. At the right, a tree with branches overspreading the horseman. In front, a raven bending towards him. (218 A.D.)

b. A similar coin.

c. Obverse: Alexander Severus. Reverse: Men-Mithra on horseback advancing towards the right. In the foreground, a flaming altar; in the roar, a tree upon which a raven is perched.

d. A similar coin, having on its obverse the bust of Gordianus III. (T. et M., p. 190.)

did prepare for the intimate union which was soon to be effected in the West between the Mysteries of Mithra and those of the Great Mother.

On the coins of the Scythian kings Kanerkes and Hooerkes, who reigned over Kabul and the Northwest of India from 87 to 120 A.D., the image of Mithra is found in company with those of other Persian, Greek, and Hindu gods. These coins have little direct connection with the Mysteries as they appeared in the Occident, but they merit our attention as being the only representations of Mithra which are found outside the boundaries of the Roman world.

a. Obverse: An image of King Kanerkes. Reverse: An image of Mithra.

b. The obverse has a bust of King Hooerkes, and the reverse an image of Mithra as a goddess.

c. Bust of Hooerkes with a lunar and a solar god (Mithra) on its reverse side.

d. Bust of Hooerkes, with Mithra alone on its reverse.

e, f, g. Similar coins. (T. et M., p. 186.)

When, as the outcome of the expedition of Alexander (334-323 B.C.), the civilization of Greece spread throughout all Hither Asia, it impressed itself upon Mazdaism as far east as Bactriana. Nevertheless, Iranism, if we may employ such a designation, never surrendered to Hellenism. Iran proper soon recovered its moral autonomy, as well as its political independence; and generally speaking, the power of resistance offered by Persian traditions to an assimilation which was elsewhere easily effected is one of the most salient traits of the history of the relations of Greece with the Orient. But the Magi of Asia Minor, being much nearer to the great foci of Occidental culture, were more vividly illumined by their radiation. Without suffering themselves to be absorbed by the religion of the conquering strangers, they combined their cults with it. In order to harmonize their barbaric beliefs with the Hellenic ideas, recourse was had to the ancient practice of identification. They strove to demonstrate that the Mazdean heaven was inhabited by the same denizens as Olympus: Ahura-Mazda as Supreme Being was confounded with Zeus; Verethraghna, the victorious hero, with Heracles; Anâhita, to whom the bull was consecrated, became Artemis Tauropolos, and the identification went so far as to localize in her temples the fable of Orestes. Mithra, already regarded in Babylon as the peer of Shamash, was naturally

Fig. 4

TYPICAL REPRESENTATION OF MITHRA.

(Famous Borghesi bas-relief in white marble, now in the Louvre, Paris, but originally taken from the mithræum of the Capitol.)

Mithra is sacrificing the bull in the cave. The characteristic features of the Mithra monuments are all represented here: the youths with the upright and the inverted torch, the snake, the dog, the raven, Helios, the god of the sun, and Selene, the goddess of the moon. Owing to the Phrygian cap, the resemblance of the face to that of Alexander, and the imitation of the motif of the classical Greek group of Nike sacrificing a bull,--all characteristics of the Diadochian epoch,--the original of all the works of this type has been attributed to an artist of Pergamon. (T. et M., p. 194.)

associated with Helios; but he was not subordinated to him, and his Persian name was never replaced in the liturgy by a translation, as had been the case with the other divinities worshipped in the Mysteries.

The synonomy thus speciously established

Artistic Type.

(Bas-relief, formerly in domo Andreæ Cinquinæ, now in St. Petersburg. T. et M., p. 229.)

between appellations having no relationship did not remain the exclusive diversion of the mythologists; it was attended with the grave consequence that the vague personifications conceived by the Oriental imagination now

assumed the precise forms with which the Greek artists had invested the Olympian gods. Possibly they had never before been represented in the guise of the human form, or if images of them existed in imitation of the

Artistic Type (Second Century).

(Grand group of white marble, now in the Vatican. T. et M., p. 210)

Assyrian idols they were doubtless both grotesque and crude. In thus imparting to the Mazdean heroes all the seductiveness of the Hellenic ideal, the conception of their character was necessarily modified; and, pruned of their exotic features, they were rendered

more readily acceptable to the Occidental peoples. One of the indispensable conditions for the success of this exotic religion in the Roman world was fulfilled when towards the second century before our era a sculptor of the school of Pergamon composed the pathetic

Early Artistic Type.

(Bas-relief of white marble, Rome, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

group of Mithra Tauroctonos, to which universal custom thenceforward reserved the place of honor in the apse of the spelæa. 1

But not only did art employ its powers to soften the repulsive features which these rude

Mysteries might possess for minds formed in the schools of Greece; philosophy also strove to reconcile their doctrines with its teachings, or rather the Asiatic priests pretended to discover in their sacred traditions the theories of the philosophic sects. None of these sects so readily lent itself to alliance with the popular devotion as that of the Stoa, and its influence on the formation of Mithraism was profound. An ancient myth sung by the Magi is quoted by Dion Chrysostomos 1 on account of its allegorical resemblance to the Stoic cosmology; and many other Persian ideas were similarly modified by the pantheistic conceptions of the disciples of Zeno. Thinkers accustomed themselves more and more to discovering in the dogmas and liturgic usages of the Orientals the obscure reflections of an ancient wisdom, and these tendencies harmonized too much with the pretensions and the interest of the Mazdean clergy not to be encouraged by them with every means in their power.

But if philosophical speculation transformed the character of the beliefs of the Magi, investing them with a scope which they did not originally possess, its influence was nevertheless upon the whole conservative rather than revolutionary. The very fact that it invested legends which were ofttimes puerile with a symbolical significance, that it furnished

rational explanations for usages which were apparently absurd, did much towards insuring their perpetuity. If the theological foundation of the religion was sensibly modified, its liturgic framework remained relatively fixed, and the changes wrought in the dogma were in accord with the reverence due to the ritual. The superstitious formalism of which the minute prescriptions of the Vendidad were the expression is certainly prior to the period of the Sassanids. The sacrifices which the Magi of Cappadocia offered in the time of Strabo (circa 63 B.C.-21 A.D.) are reminiscent of all the peculiarities of the Avestan liturgy. It was the same psalmodic prayers before the altar of fire; and the same bundle of sacred twigs (baresman); the same oblations of milk, oil, and honey; the same precautions lest the breath of the officiating priest should contaminate the divine flame. The inscription of Antiochus of Commagene (69-34 B.C.) in the rules that it prescribes gives evidence of a like scrupulous fidelity to the ancient Iranian customs. The king exults in having always honored the gods of his ancestors according to the tradition of the Persians and the Greeks; he expresses the desire that the priests established in the new temple shall wear the sacerdotal vestments of the same Persians, and that they shall officiate conformably to the ancient sacred custom. The sixteenth day of each month, which is to be

specially celebrated, is not to be the birthday of the king alone, but also the day which from time immemorial was specially consecrated to Mithra. Many, many years after, another

Fig. 8.

KING ANTIOCHUS AND AHURA-MAZDA.

(Bas-relief of the temple of Antiochus I. of Commagene, 69-34 B.C., on the Nemrood Dagh, a spur of the Taurus Mountains. T. et M., p. 188.)

Commagenean, Lucian of Samosata, in a passage apparently inspired by practices he had witnessed in his own country, could still deride the repeated purifications, the interminable chants, and the long Medean robes of the

sectarians of Zoroaster. 1 Furthermore, he taunted them with being ignorant even of Greek and with mumbling an incoherent and unintelligible gibberish. 2

The conservative spirit of the Magi of Cappadocia, which bound them to the time-worn usages that had been handed down from generation to generation, abated not one jot of its power after the triumph of Christianity; and St. Basil 3 has recorded the fact of its persistence as late as the end of the fourth century. Even in Italy it is certain that the Iranian Mysteries never ceased to retain a goodly proportion of the ritual forms that Mazdaism had observed in Asia Minor time out of mind. 4 The principal innovation consisted in substituting for the Persian as the liturgic language, the Greek, and later perhaps the Latin. This reform presupposes the existence of sacred books, and it is probable that subsequently to the Alexandrian epoch the prayers and canticles that had been originally transmitted orally were committed to writing, lest their memory should fade forever. But this necessary accommodation to the new environments did not prevent Mithraism from

preserving to the very end a ceremonial which was essentially Persian.

The Greek name of "Mysteries" which writers have applied to this religion should not mislead us. The adepts of Mithraism did not imitate the Hellenic cults in the organization of their secret societies, the esoteric doctrine of which was made known only after a succession of graduated initiations. In Persia itself the Magi constituted an exclusive caste, which appears to have been subdivided into several subordinate classes. And those of them who took up their abode in the midst of foreign nations different in language and manners were still more jealous in concealing their hereditary faith from the profane. The knowledge of their arcana gave them a lofty consciousness of their moral superiority and insured their prestige over the ignorant populations that surrounded them. It is probable that the Mazdean priesthood in Asia Minor as in Persia was primitively the hereditary attribute of a tribe, in which it was handed down from father to son; that afterwards its incumbents consented, after appropriate ceremonies of initiation, to communicate its secret dogmas to strangers, and that these proselytes were then gradually admitted to all the different ceremonies of the cult. The Iranian diaspora is comparable in this respect, as in many others, with that of the Jews. Usage soon distinguished between the different

classes of neophytes, ultimately culminating in the establishment of a fixed hierarchy. But the complete revelation of the sacred beliefs and practices was always reserved for the privileged few; and this mystic knowledge appeared to increase in excellence in proportion as it became more occult.

All the original rites that characterized the Mithraic cult of the Romans unquestionably go back to Asiatic origins: the animal disguises used in certain ceremonies are a survival of a very widely-diffused prehistoric custom which still survives in our day; the practice of consecrating mountain caves to the god is undoubtedly a heritage of the time when temples were not yet constructed; the cruel tests imposed on the initiated recall the bloody mutilations that the servitors of Mâ and of Cybele perpetrated. Similarly, the legends of which Mithra is the hero cannot have been invented save in a pastoral epoch. These antique traditions of a primitive and crude civilization subsist in the Mysteries by the side of a subtle theology and a lofty system of ethics.

An analysis of the constituent elements of Mithraism, like a cross-section of a geological formation, shows the stratifications of this composite mass in their regular order of deposition. The basal layer of this religion, its lower and primordial stratum, is the faith of ancient Iran, from which it took its origin.

Above this Mazdean substratum was deposited in Babylon a thick sediment of Semitic doctrines, and afterwards the local beliefs of Asia Minor added to it their alluvial deposits. Finally, a luxuriant vegetation of Hellenic ideas burst forth from this fertile soil and partly concealed from view its true original nature.

This composite religion, in which so many heterogeneous elements were welded together, is the adequate expression of the complex civilization that flourished in the Alexandrian epoch in Armenia, Cappadocia, and Pontus. If Mithridates Eupator had realized his ambitious dreams, this Hellenized Parseeism would doubtless have become the state-religion of a vast Asiatic empire. But the course of its destinies was changed by the vanquishment of this great adversary of Rome (66 B.C.). The débris of the Pontic armies and fleets, the fugitives driven out by the war and flocking in from all parts of the Orient, disseminated the Iranian Mysteries among that nation of pirates that rose to power under the protecting shelter of the mountains of Cilicia. Mithra became firmly established in this country, in which Tarsus continued to worship him until the downfall of the empire (Figure 9). Supported by its bellicose religion, this republic of adventurers dared to dispute the supremacy of the seas with the Roman colossus. Doubtless they considered themselves the chosen

nation, destined to carry to victory the religion of the invincible god. Strong in the consciousness of his protection, these audacious mariners boldly pillaged the most venerated sanctuaries

Fig. 9.

MITHRAIC MEDALLION OF BRONZE FROM TARSUS, CILICIA.

Obverse: Bust of Gordianus III., clad in a paludamentum and wearing a rayed crown. Reverse: Mithra, wearing a rayed crown and clad in a floating chlamys, a tunic covered by a breast-plate, and anaxyrides (trousers), seizes with his left band the nostrils of the bull, which he has forced to its knees, while in his right hand he holds aloft a knife with which he is about to slay the animal. (T. et M., p. 190.)

of Greece and Italy, and the Latin world rang for the first time with the name of the barbaric divinity that was soon to impose upon it his adoration.

2:1 Oldenberg, Die Religion des Veda, 1894, p. 185.

4:1 Zend-Avesta, Yasht, X., Passim.

7:1 Yasht, X., 103.

7:2 Plutarch, De Iside et Osiride, 46-47; Textes et monuments, Vol. II., p. 33.

7:3 West, Pahlavi Texts, I. (also, Sacred Books of the East, V.), 1890, p. 3, et seq.

9:1 Ctesias apud Athen., X., 45 (Textes et monuments, hereafter cited as "T. et M.," Vol. II., p. 10).

10:1 Ptol., Tetrabibl., II., 2.

13:1 Michel, Recueil inscr. gr., No. 735. Compare T. et M., Vol. II., p. 89, No. 1.

17:1 M. Jean Réville (Études de théologie et d'hist. publ. en hommage à la faculté de Montauban, Paris 1901, p. 336) is inclined to accord a considerable share in the formation of Mithraism to the religions of Asia; but it is impossible in the present state of our knowledge to form any estimate of the extent of this influence.

24:1 Compare the Chapter on ''Mithraic Art."

25:1 Dion Chrys., Or., XXXVI., §39, et seq. (T. et M., Vol. II., p. 60, No. 461).

28:1 Luc., Menipp., c. 6 (T. et M., Vol. II., p. 22).

28:2 Luc., Deorum conc., c. 9, Jup. Trag., c. 8, c. 13 (T. et M., ibid.)

28:3 Basil., Epist. 238 ad Epiph. (T. et M., Vol. I., p. 10, No. 3). Compare Priscus, fr. 31 (I. 342 Hist. min., Dind.).

28:4 See the Chapter on "Liturgy, Clergy, &c."