Sacred Texts Symbolism Index Previous Next

The Migration of Symbols, by Goblet d'Alviella, [1894], at sacred-texts.com

I. The Sacred Tree and its acolytes.—The Tree in the art and symbolism of Mesopotamia.—The Tree between two animals, or two monsters; adoption of this theme by the Persians, Phœnicians, Greeks, Hindus, Arabs, and Christians.—The Tree between two human personages; its migrations into Persia, India, and the extreme East.—Characteristic features of the images derived from these two themes.—The variety of certain details does not preclude relationship between symbolical combinations.—Substitution of sacred objects for the Tree between its acolytes.

II. Interpretation of the Sacred Tree amongst the Semites.—The Sacred Tree does not merely represent a plant venerated for its uses.—Simulacra of the Goddess of Nature; the asherîm.—The representation of the artificial fertilization of the palm-tree became, in Assyria, the symbol of fecundation in general.—Myths and symbols relating to the Tree of Life.—The Cosmogonical Tree in the cuneiform texts.—The Tree of Knowledge.—The Calendar Plant or Lunar Tree.

III. The Paradisaical Trees of the Aryans.—Mythical Trees of the Hindus.—The Tree of Knowledge amongst the Buddhists, and its connection with the Cosmic Tree.—Contests for the fruit of the Tree.—Analogous myths amongst the Persians, Greeks, and Scandinavians.—How far this similarity of traditions denotes a common source.—Logical coincidences in the applications of vegetable symbolism.—Enrichment and approximation of mythologies by the mutual exchange of myths and symbols.

The Tree is one of the oldest and most widely diffused subjects in Semitic pictorial art, especially in Mesopotamia. 1 It first appears, on Chaldæan

cylinders, as a stem divided at the base, surmounted by a fork, or a crescent, and cut, mid-way,

Fig. 61. Rudimentary Forms of the Sacred Tree 1

by one or more cross-bars, which sometimes bear a fruit at each extremity.

Fig. 62. Varieties of Sacred Trees 2

This rudimentary image frequently changes into

the palm, the pomegranate, the cypress, the vine, etc. (fig. 62).

On the monuments of Nimrud and Khorsabad, beginning with the tenth century before our era, the

Fig. 63. Conventional Trees of Assyrian Bas-Reliefs.

Tree becomes still more complex; it would sometimes seem to be composed of fragments belonging to different kinds of plants. The stem, which suggests a richly ornamented Ionic column, is crowned by a palmette; the base is concealed

behind a bunch of slender loaves, which, in some cases, recall our fleur-de-lis (fig. 62e), or else it rests upon a pair of fluted horns, which recur again at the top and even in the middle of the stem (fig. 63). On both sides branches spread out symmetrically, bearing conical fruits (fig. 63b), or fan-shaped leaves (fig. 63c), at their extremities. Sometimes the ends of these branches are connected by straps which form a net-work of the most pleasing effect. 1

Whatever the ornamental value of this figure may be, it is certain that it has, above all, a religious

Fig. 64. The Acolytes Of The Sacred Tree.

(Lajard. Mithra, pl. xlix., fig. 9.

signification. It is invariably associated with religious subjects, among the intaglios of the cylinders, the sculptures of the bas-reliefs, and the embroidery of the royal and sacerdotal garments. Above it is frequently suspended the Winged Circle, personifying the supreme divinity, Assur at Nineveh, Bel or Ilu at Babylon. Lastly, it nearly

always stands between two personages facing each other, who are sometimes priests or kings in an attitude of adoration, sometimes monstrous creatures, such as are so often met with in Assyro-Chaldæan imagery, lions, sphinx, griffins, unicorns, winged bulls, men, or genii, with the head of an eagle, and so forth.

Hence we have two types, or symbolical combinations, whose migrations we can easily follow.

A. The Tree between two animals facing each other makes it first appearance on the oldest

Fig. 65. (From the Catalogue of the de Clercq collection, vol. i., pl. ii., 15, and pl. vii., 61.)

cylinders of Chaldæa. In the de Clercq collection it is seen on engraved stones which are attributed, one to the archaic art of Chaldæa, the other to the school that flourished, according to M. J. Menant, in the city of Agadi at the time of Sargon I., some four thousand years before our era. 1

Click to enlarge

Plate IV

Explanation of Plate IV.

Figure a is a bas-relief of Nineveh, reproduced from Layard (Monuments of Nineveh, 2nd series, pl. xlv., fig. 3).

Figure b is taken from a Phœnician bowl discovered at Cærium by M. de Cesnola, and reproduced by M. Clermont-Ganneau (L’Imagerie phénicienne. Paris, 1880, pl. iv.).

Figure c comes from a Persian cylinder inscribed with Aramean characters, the property of M. Schlumberger, and reproduced by M. Ph. Berger (Gazette archéologique for 1888, p. 143).

Figure d belongs to a bowl which was found, together with products of Sassanian art, near the White Sea (J. R. Aspelin. Antiquités du Nord Finno-Ougrien. Helsingfors, fig. 610).

Figure e is copied from a capital of the temple of Athene at Priene (O. Rayet et A. Thomas. Milet et le golfe Latinique. Paris, 1887, pl. xlix., No. 5).

Figure f reproduces the ornamentation of an archaic vase of Athens belonging to the British Museum (Rayet et Collignon. Histoire de la céramique grecque, fig. 25).

Figure g comes from the sculptures on the baptistery at Cividale (Le Monnier. L’Architecture in Italie. Venice, 1891, fig. 36).

Figure h comes from the bas-reliefs of Bharhut, probably anterior to our era (A. Cunningham. The Stupa of Bharhut, pl. vi.).

Figure i is copied from a Tanjore carpet at the India Museum in London (Sir George Birdwood. The Industrial Arts of India. London, 1880, p. 53).

Figure j is taken from a tympanum of the church at Marigny, in the Calvados department (De Caumont. Rudiments d’archéologie. Architecture religieuse. Paris, 5th edition, p. 269).

However this may be, it was only at the time of the Assyrian domination that it received its definite and so highly artistic shape. While the Tree becomes larger and more conspicuous, the two animals, no longer embracing or crossing one another, assume a more natural and strictly symmetrical attitude (see pl. iv., fig. a).

From Mesopotamia this subject passed on the one hand among the Phœnicians and into the whole of Western Asia, on the other among the Persians after the fall of Babylon.

The latter confined themselves to copying the Assyrian type on their seals, their jewels, their cloths, and their bas-reliefs, until the end of the empire of the Sassanidæ, in the seventh century of our era (pl. iv., figs. c and d).

From Persia it passed into India, doubtlessly during the period immediately preceding the invasion of Alexander. The presence of the Tree between two lions facing one another among the Buddhist sculptures of Bharhut is even one of the indications that help to prove the influence of Iranian art on the most ancient monuments of Hindu architecture (pl. iv., fig. h). 1

In the bas-reliefs of Kanheri, where the symbols of Buddhism are mingled with the reminiscences of an earlier form of worship, the Sacred Tree is sculptured as an object of veneration between two elephants facing one another, whilst in other bas-reliefs it is transformed, flanked by the same two elephants, into the Lotus-flower which forms the Throne of Buddha. 2 Lastly, after the extinction of Buddhism in India, it was resumed by the

[paragraph continues] Brahmanical sects, which confined themselves to replacing Buddha on his Lotus Throne (still between the two elephants), by Parbati, the spouse of Vishnu. 1 Moreover, we again meet with the Tree—in which Sir George Birdwood does not hesitate to recognize the Tree of Life—between two animals facing one another on the cloths, the carpets, the vases, and the jewels of contemporary India. 2 In this last case, however, it is not always easy to discriminate whether we are in the presence of a survival of pre-Islamitic symbolism, or of a reaction of Sassanian art introduced into India by the Islamic invasions (cf. fig. 60 and pl. iv., fig. i).

The Phœnicians borrowed it from Mesopotamia

Fig. 66. Stele from Cyprus.

(Perrot et Chipiez, Vol. iii., fig. 152.)

more than a thousand years anterior to our era, developing its artificial appearance until all semblance of its arboreal origin has well-nigh vanished, to be replaced by an interlacing of spirals and strap-like curves (pl. iv., fig. b).

[paragraph continues] Some of those combinations, in which winged sphinxes cling to the spirals, betray a singular medley of Egyptian influences, whilst at the same time already suggesting the elegant modifications of Greek art. 1

This type, as conventional as it is æsthetic, occurs wherever Phœnician influence was felt, more especially among the archaic pottery of Corinth and of Athens (pl. iv., fig. f). Perhaps it had already penetrated directly into Greece through Asia Minor, for it is seen on an amphora, discovered by General de Cesnola at Curium, which MM. Rayet and Collignon place among the vases with geometric decorations belonging to an

FIG. 67. VASE FROM CURIUM. (CESNOLA. Cyprus, chap. i., p. 55.)

Fig. 67. Vase From Curium.

(Cesnola. Cyprus, chap. i., p. 55.)

earlier time than the period of Phœnician influence. The Tree preserves here a more natural appearance; it is placed between two quadrupeds standing on their hind legs and overlooking the stem. This brings us back to the Chaldæan prototype of our fig. 65.

If it did not furnish the Greeks with the first idea of the palmette and the honeysuckle ornament, it certainly suggested the decoration of certain capitals, such as those of the temple of Apollo at Didyme, and of Athene Polias at Priene (pl. iv., fig. e). 2

Greece, however, seems only to have made use of it by way of exception. If it penetrated into Italy, and even into Gaul, along with the other products of Oriental imagery, it did not become an ordinary motive of classic art. We may draw attention to its presence, by the way, in a decorative painting at Corneto, 1 and on a Gallic coin found near Amiens, and attributed to the commencement of our era.

Following in the footsteps of M. Hucher, I had at first taken the object engraved on this coin between

Fig. 68. Gallic Coin.

(Hucher. L’art gaulois, vol. ii., p. 36.)

two quadrupeds to be a cup or drinking vessel. But my attention has been directed to some intaglios of Cyprus, and even of Chaldæa, where the tree assumes the form of a staff supporting a semicircle, as in the figure 61d given above. M. Hucher, with his usual perspicacity, thinks that the subject engraved on this coin belongs "to the same train of thought as that which in antiquity brought face to face the lions of Mycenæ on the gates of that town, and the lions of the Arab or Sassanian fabric of Mans on the shroud of St. Bertin, or even, in the thirteenth century, the doves with serpents’ tails on the capitals of the cathedral at Mans." It is strange to note the presence of the same theme, dealt with in an identical manner, on a fibula discovered

near Geneva, which M. Blavignac considers to be of Christian origin. 1

However, it is by another way that it was introduced into Christian symbolism. It was, in fact, taken directly from the Persians by the Byzantines about the seventh century of our era. The influence of Sassanian art had made itself felt in the Byzantine Empire from the time of the death of Theodosus, if not earlier. "The Byzantines," says M. Charles Bayet, "did not invent all the ornamental combinations from which they got such pleasing effects; in this instance again they borrowed them from the East, and on the monuments of Persia models are found from which they drew their inspirations." 2 The same writer proves that in the sixth and seventh centuries the apartments of the rich, and even the treasures of the churches, were filled with stuffs which came from Persia, or which reproduced the subjects of Persian art. 3 It is related that even Justinian had employed a Persian architect to decorate several buildings in Constantinople. 4 Under these circumstances, how could the Byzantines help adopting one of the most pleasing and widely diffused Sassanian themes of decoration, which lent itself both to the refinements of ornamentation and to the fancies of the symbolical imagination? This is, moreover, the way by which the whole fantastic fauna of the East entered Europe, to form the Christian symbolic menagery of the Middle Ages. 5

From the Grecian provinces it was introduced into Italy, where it is often found in religious architecture between the seventh and the eleventh centuries in Sicily, at Ravenna, and especially at Venice (see pl. iv., fig. g, and also fig. 58). Here it was even taken up and reproduced by the Renaissance, as may be seen at Santa Maria del Miracoli, at the Scuola of San Marco, etc. 1

Finally, it crossed the Alps with Roman art. M. de Caumont was one of the first to draw attention to its presence amongst the sculptures of the Roman period, in particular on a tympanum of the church at Marigny, in the Calvados department. It is here sculptured between two lions, which hold the stem with their fore-paws, and bite at the extremities of the middle branches (pl. iv., fig. j). 2

What a strange fate for this antique symbol, which, after being used for several thousand years in the long since vanished worships of Higher Asia, came thus to be stranded, in the western extremity of Europe, on the sanctuary of a religion possessing also amongst its oldest traditions the reminiscence of the Paradisaical Trees of Mesopotamia! 3

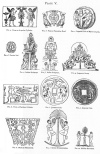

Click to enlarge

Plate V

Explanation of Plate V.

Figure a is taken from an Assyrian cylinder (Lajard. Mithra, pl. lxi., fig. 6).

Figure b, from the ornamentation of a Phœnician bowl (Clermont Ganneau. L’Imagerie phénicienne, pl. vi.).

Figure c, from an imperial coin of Myra in Lycia (COLLIGNON. Mythologie figurée de la Grèce. Paris, Bibliothèque des Beaux-Arts, p. 10).

Figure d, from a Persian seal (Lajard. Mithra, pl. xliv., xlvi., No. 3).

Figure e, from the sculptures in the caves of Kanerki (Ferguson and Burgess. Cave Temples of India, pl. x., fig. 35).

Figure f, from the bas-reliefs in the cave of Karli (Moor. Hindu Pantheon, pl. lxxii.).

Figure g, from a wooden group in the Musée Guimet.

Figure h, from a Chaldean cylinder (Lajard. Mithra, pl. xvi., fig. 4).

Figures i and j, from coins of the Javanese temples (Millies. Monnaies de l’Archipel Indien, pl. vi., fig. 50, and pl. ix., fig. 67).

Figure k, from a Maya manuscript known by the name of the Fejervary Codex (Publications of the Bureau of Ethnography. Washington, 1882, vol. iii., p. 32).

Figure l, from the ornamentation of a modern Syrian copper dish inscribed with cufic characters, presented by the Count Goblet d’Alviella to Sir George Birdwood.

Figure m, from the bas-reliefs of the cathedral at Monreale (D. B. Gravinat. Il duomo di Monreale. Palermo, 1859, pl. xv., H).

B. The image of the Tree between two human (or semi-human) personages invariably facing one another followed at first almost the same route as the type whose migrations I have just described. The two themes are sometimes combined, as we see, in Assyria itself, on the cylinder reproduced above (fig. 64). Modified considerably by Greek art, like all symbols which made use of the human figure (pl. v., fig. c, and below, figs. 69 and 83), it remained more faithful to its earliest type in Phœnicia (pl. v., fig. b), in Persia (pl. v., fig. d), and even in India, where the two Assyrian eagle-headed genii (pl. v., fig. a), which advance towards the Tree holding the symbolical Cone, became the two naga-rajahs, or "snake-kings,"—their heads entwined with cobras—who support the stem of the Buddhist Lotus (pl. v., fig. e). In the grottoes of Karli this stem, which serves as a support to the Throne of the Master, stands erect both between two of those naga-rajahs and two deer facing one another (pl. v., fig. f).

These sculptures date back to a period which cannot be prior to the reign of Asoka, i.e., the middle of the third century B.C., nor much later than the beginning of our era. It is interesting to again come across them, at an interval, perhaps, of two thousand years, in Japanese wooden groups of the seventeenth century belonging to the Guimet Museum. In one of them the naga-rajahs bear a genuine dragon on their shoulders; this substitution, together with some differences in the costume and the figure of these personages, is almost the only liberty which the native art took with the old Buddhist subject, long since forgotten in its original home (pl. v., fig. g).

From India it reached, in company with Buddhism, the island of Java, where we meet with it upon those curious medals of temples which the natives, although converted centuries ago to

[paragraph continues] Islamism, continue to wear by way of talismans. It occurs there, amongst other Buddhist symbols, between two figures with human bodies and beasts’ or birds’ heads,—which is surely the Mesopotamian conception in all its integrity (pl. v., figs. i and j).

It is also found in China on Taoist medals, recalling the coins of the Javanese temples. 1 Here, however, the disposition of the Tree, as also the costume of the personages, refer to quite a different type, whether it be that we are here in the presence of a corruption of Javanese coins, or that these, in imitating the Taoist coins, cast, so to speak, the subject of the latter in a mould provided by the Buddhist symbols of India.

From the Indian Archipelago—or from Eastern Asia—it may have even reached the New World, if we are to judge from the resemblance of the scene depicted on the Javanese medals to certain images found in manuscripts connected with the ancient civilization of Central America.

We have seen that the Cross was used, in the symbolism of the ancient inhabitants of America, to represent the winds which bring the rain. These crosses sometimes assume a tree-like form, and are then composed of a stem bearing two horizontal branches, with a bird perched on the fork, as in the famous stele of Palenque. 2 Moreover, this tree is sometimes placed between two personages facing one another, with a sort of wreath of feathers on their heads, who cannot but. recall the monstrous aspect of the beings depicted on both sides of the Tree upon the medals of Javanese temples. The reproduction which I

here give (pl. v., fig. k) from the Fejervary Codex 1 shows up this parallel all the more, since it is placed close to medals of Java and underneath a Chaldæan cylinder which might be almost made the prototype of all these images (pl. v., fig. h).—We have here certainly fresh evidence in favour of the theory which already relies upon so many symbolical and ornamental similarities in order to discover, in the pre-Columbian civilization of America, the traces of intercourse with Japan, China, or the Indian Archipelago.

Finally, by a singular case of atavism, this subject, which already adorned the Chaldæan cylinders of five or six thousand years ago, reappears in our own times in the decoration of the copper vases or plates, known as mosouli, which are still manufactured in Syria, on the banks of the Euphrates and the Tigris (pl. v., fig. l). There is still the palm-tree between its two acolytes,—henceforth dressed as fellahin,—who are engaged in plucking the two large fruits, or rather conventional clusters, suspended side by side beneath the crown.

On the other hand, it was quite adapted to furnish the first Christian artists with a model of the scene of the Temptation; all that was needed was to give a different sex to the two acolytes (pl. v., fig. m). Already in the art of the Catacombs it frequently occurs with this application. 2

The cabinet of antiquities at the Bibliothèque Nationale of Paris possesses a cameo which has likewise been held to represent the scene of the Temptation, although it depicts the quarrel between Poseidon and Athene under the sacred olive-tree,

in the presence of the serpent Erichthonios. 1 What makes the case very interesting is, not only that we have here engraved upon the stone the Hebrew text of Genesis III. 6, but that we also find at work those touching-up processes which were sometimes made use of in order to

Fig. 69. Antique Cameo.

(Babelon. Cabinet des Médailles, pl. xxvi.)

adapt a pre-existent image to the expression of a new tradition.

The olive-tree has been changed into an apple-tree. Neptune's Trident and Minerva's Spear have been scraped out. The attempt has even been

made to transform into some sort of a head-dress the helmet, inappropriate enough, to be sure, on the head of our first mother, and in her companion's hand has been placed a round object, which may pass for an apple.

To be sure, the occurrence of the representation of a tree between two animals or personages, even when facing one another, is not in itself sufficient for one to infer that it is connected with the types described above. Yet, in the examples I have given, the original identity of the inspiration may be verified, not only by a general resemblance spread throughout the whole image,—we might call it a family likeness,—but also by the presence of certain features, its ineffacable characteristics, so to speak, by which it may everywhere be recognized.

In the first place, there is the symmetry in the expression and attitude of the two acolytes, often also in the form of the Tree and the arrangement of the branches. Then we have the presence, often unaccountable, of a pair of volutes between which the stem rises. These two spirals sometimes represent branches, or petals, of flowers (pl. iv., figs. a, b, c, e, g, i, j,; pl. v., figs. a, d, h, i, l), sometimes curved horns (figs. 63, 64; pl. iv., figs. a, b, e, f, g, i, j; pl. v., figs. a, b, f, i, k). We may, perhaps, attribute their origin either to the conventional representation of the clusters which adorn the image of the Chaldæan Palm-tree, or to the introduction of the horns which were amongst the Assyrians a distinguishing sign of the divinity.

Finally, a detail which seems to be equally characteristic of the Sacred Tree in the most different countries is the appearance of serpents, which sometimes twine themselves round the stem (figs. 60, 69, 83; pl. iv., fig. d; pl. v., figs. c, e, f, g, m), and sometimes figure merely in the

background of the image (fig. 59, and pl. v., fig. h).

It must be observed that it is not the identity of the species of plants which constitutes the essential feature of the symbol through all its local modifications, but rather the constant reappearance of its hieratic accessories.

Each nation seems, indeed, to have introduced into this symbolical combination the tree which it deemed the most valuable. Thus we see depicted in turn the date-palm in Chaldæa, the vine or a cone-bearing plant in Assyria, the lotus in Phœnicia, and the fig-tree in India. 1

Moreover, following in the footsteps of the Assyrians, who had inserted into this Tree features which were quite extraneous to the vegetable kingdom, some creeds replaced the plant itself by other sacred objects.

The Phrygians placed the representation of a pillar, a phallus, or an urn, between winged sphinxes,

Fig. 70. Tomb At Kumbet.

(Perrot et Chipiez. Histoire de l’Art, vol. V., fig. 84.)

lions, or bulls, facing each other, as is still to be seen on the pediments of the tombs hewn in the rocks of Phrygia. As M. Perrot observes: "Though one element is substituted for another,

the group preserves none the less the same character." 1

On a cylinder, which M. Menant considers of

Fig. 71. Hittite Cylinder.

(De Clercq collection, vol. i. of Catalogue, pl. xxviii., No. 289.)

[paragraph continues] Hittite origin, the arborescent stalk becomes a Winged Globe.

The Pelopides of Mycenæ, and, later, the Persians, put in its stead a pyre or fire-altar. 2

Fig. 72. Persian Cylinder.

(Ch. Lenormant, in the Mélanges d’archéologie, vol. iii., pp. 130 and 131.)

[paragraph continues] The group which formerly surmounted the celebrated gate of Mycenæ certainly represented an object of this nature between lions facing one another (fig. 73).

The Buddhists introduced their principal "jewels" into the image, as may be seen in the following reproduction of a small portable altar, where the object, portrayed between two animals in a crouching attitude, represents perhaps the

astronomical emblem of the nine planets, the

Fig. 73. Gate of Mycenæ.

(Schliemann. Mycènes.)

nava-ratna, borrowed by Buddhist symbolism from the Hindus (fig. 74).

Fig. 74. Tibetan Symbol.

(Hodgson. Journ. of the Roy. Asiatic Soc., vol. xviii., 1st series, pl. i., No. 18.)

In Chinese and, perhaps, Japanese art, the "great jewel" becomes a pearl, frequently depicted between two dragons facing one another, with partly-open jaws. We may, perhaps, find a curious application of this symbol in the customs of the Chinese. M. de Groodt relates that in the festival of lanterns they lead about a dragon made of cloth and bamboo, before whose mouth they wave a round lantern like a ball or pearl of fire,—whether this scene represents the conflict of the celestial bodies with the devouring dragon, in keeping with the Chinese conception of eclipses,

or the vain efforts of falsehood to swallow up truth. 1

We have seen above that the Greeks, in imitation of the Phœnicians, represented between

Fig. 75a. Bas-Relief on a Sarcophagus.

(Millin. Voyage dans le Midi, pi. lxv.)

Fig. 75b. Christian Sculpture of the Third Century.

(Roller. Catacombes, vol. i., p. 53.)

two birds the bethel of the Cyprian Aphrodite and the omphalos of the Delphic Apollo, thus creating a new theme less extravagant and fantastic. The Christians, in their turn, from the time of the Catacombs, placed two figures on the sides of their principal emblems,—not only of the Cross, which is

also called "a Tree of Life," but also of the Chrism, the labarum, the rouelle, the Crown, the bunch of Grapes, the eucharistic Cup, and so forth. 1 Sometimes these figures are lambs, and sometimes peacocks, or doves (fig. 75, a and b).

Among the wooden ornaments of Romoaldus’ episcopal throne in San Sabino at Canossa, we even find the mystic candelabrum thus sculptured between two griffins:

Fig. 76. Wooden Sculpture at Canossa.

(H. W. Schultz. Kunst des Mittelalters in Italien, pl. vi., fig. 1.

Then chivalry placed its coats of arms between the two creatures facing one another,—lions, leopards, unicorns, griffins, giants, etc. Charles Lenormant was not mistaken in saying, with respect to the filiation of these types: "When the use of armorial bearings began to develop in the West, Europe was deluged with the manufactured articles of Asia, and the first lions drawn on escutcheons were certainly copied from Persian and Arabian tissues. These tissues themselves dated back, from one imitation to another, to the models from which, perhaps, over a thousand years before Christ, the author of the bas-reliefs of Mycenæ, drew his inspiration." 2

The same tendency is still at work. When, more than half-a-century ago, the Royal Institute of British Architects wished to have armes parlantes,

it chose a Corinthian column, on the sides of which it placed two British lions facing each other.

Fig. 77. Seal of the R. Inst. of British Architects.

Some time ago, while on a visit to the fine estate, well-known in the country round Liege under the name of the Rond-Chêne, I observed, sculptured on a mantelpiece of recent construction, an oak of pyramidal form with a heraldic griffin on either side. On inquiring whether these were not the old armorial bearings of the domain, I was told that it was merely an artistic conceit, suggested by the name of the locality. I could not give a better instance of how the sculptor, or engraver, even whilst yielding to quite a different inspiration, upholds, nevertheless, a tradition unbroken for thirty centuries, and obeys, more or less consciously, a law which may be formulated thus: When an artist wants to bring into prominence, as a symbol, the isolated image of an object which lends itself to a symmetrical representation, particularly a tree or pillar, he places on either side two creatures facing one another,—giving rise sometimes, in return, to a myth or legend in order to account for the combination.

118:1 Joachin Menant. Les pierres gravées de la Haute-Asie. Paris, 1883–86, vol. i., figs. 41, 43, 71, 86, 704, 115, 120, 121, p. 119 and 142; vol. ii., figs. 11, 13, 17, 18, 19, 36, 41, 54 to 61, 85, 110, 208, 213, etc.

119:1 a is taken from a Chaldæan cylinder (J. Menant, Pierres gravées, vol. i., fig. 71); b, from a cylinder of Nineveh (Layard, Monuments of Nineveh, 2nd series, pl. ix., No. 9); c, from a Chaldean cylinder (J. Menant, Pierres gravées, vol. i., fig. 115); d, from an Assyrian cylinder (Perrot et Chipiez, Histoire de l’art dans l’antiquité, vol. ii., fig. 342).

119:2 a (Menant, Pierres gravées, vol. i., fig. 86); b (Lajard, Mithra, pl. xxxix., fig. 8); c (Perrot et Chipiez, Histoire de l’art, vol. ii., fig. 235); d (Seal of Sennacherib, Menant, Pierres gravées, vol. ii., fig. 85).

121:1 Layard. Monuments of Nineveh, 1st series, pl. 6, 7, 8, 9, 25, 39, 44.—G. Rawlinson. The Five Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World. London, 1862–67, vol. ii., pp. 236, 237.—See also passim in the Atlas, appended by Félix Lajard to his Introduction à l’étude du culte de Mithra.

122:1 The object engraved between the two monsters in fig. 65a is, according to the Catalogue of the de Clercq collection, a candelabrum. I think that we must rather see in this a tree of the kind reproduced above (fig. 62c), from a bas-relief in the Louvre. Moreover, the Tree, the Candelabrum, and the Column, are images which merge into one another with the greatest ease (cf. below, fig. 76). The two objects have not only a resemblance of form, but also of idea, on which matter I cannot do better than refer the reader to the chapter entitled The p. 123 Jewel Bearing Tree in Mr. W. R. Lethaby's recent work, Architecture, Mysticism, and Myth.

123:1 A. Cunningham. The Ships of Bharhut. London, 1879, pl. vi. and vii.

123:2 Fergusson and Burgess. Cave Temples of India. London, 1880, p. 350.

124:1 Moor. Hindu Pantheon, pl. 30.

124:2 Sir George Birdwood. Industrial Arts of India. London, 1880, p. 350.

125:1 Sara Yorke Stevenson. On certain Symbols of some Potsherds from Daphnæ and Naucratis. Philadelphia, 1892, p. 13 et seq.

125:2 O. Rayet and A. Thomas. Milet et le golfe Latinique. Paris, 1877, pl. xvii., No. 9, and pl. xlix., No. 5.

126:1 J. Martha. Archéologie Etrusque et Romaine. Paris, fig. 8.

127:1 J. D. Blavignac. Histoire de l’architecture sacrée à Genève. Paris, Atlas, pl. ii., fig. 2.

127:2 L’Art Byzantin. Paris, p. 60.

127:3 Id., chap. iii.

127:4 Batissier, quoted by E. Soldi. Les Arts méconnus. Paris, 1881, p. 252.

127:5 The Tree between two lions facing one another appears already on an ivory casket which Millin attributes to an early period of the Byzantine Empire, and which is now in the p. 128 cathedral of Sens. (Voyage dans les Départements du Midi. Paris, 1807, pl. x. of Atlas.)

128:1 Bachelin Deflorenne. L’Art, la Décoration et l’Ornement des Tissus. Paris, pl. iv. and xiii.

128:2 It is generally the griffin which is chosen in preference, perhaps because it symbolizes vigilance.

128:3 The Arabs adopted it in their turn, when they had overthrown the Sassanian dynasty, but divesting it of all religious signification. Through their agency it reached Europe towards the beginning of the Middle Ages, together with the stuffs which are still extant in private and public collections, in treasures of churches, and so forth. (See Anciennes étoffes in the Mélanges d’archéologie of MM. Ch. Cahier and A. Martin, vol. i., pl. 43; vol. ii., pl. 12 and 16; vol. iii., pl. 20 and 23; vol. iv., pl. 24 and 25.) It is also to be seen on a golden vase, adorned with enamelled partition work, which belongs to the church of Saint-Martin-en-Valais, and which is said to have been sent to Charlemagne by the Caliph Haroun Al Rashid.

130:1 Specimens of these medals are to be found in the department of medals in the Bibliothèque Nationale at Paris.

130:2 A bird perched on the fork of the Sacred Tree is likewise seen on certain Persian cylinders. (Lajard. Mithra, pl. LIVc fig. 6.)

131:1 Cyrus Thomas. Notes on certain Maya and Mexican Manuscripts, in the publications of the Bureau of Ethnology. Washington, 1881–82, vol. iii., p. 32.

131:2 Garucci. Storia del’ Arte christiana, tab. xxiii., 1.

132:1 Babelon. Le Cabinet des Médailles d la Bibliothèque nationale. Paris, 1888, p. 79.

134:1 M. Didron observes, in his Manuel d’iconographie chrétienne (Paris, 1845, p. 80), that each Christian nation chose the plant which it preferred to represent the Tree of Temptation; the fig and orange-trees in Greece, the vine in Burgundy and Champagne, the cherry-tree in the Isle of France, and the apple-tree in Picardy.

135:1 Perrot et Chipiez. Op. cit., vol. v., p. 220.

135:2 See a painted vase in the Blacas collection. (Mém. de l’Acad. des inscr. et bel.-lett., vol. xvii., pl. viii.)

137:1 Les fêtes annuelles à Emoui, in vol. xi. of the Annales du Musée Guimet. Paris, 1886, p. 369.

138:1 Roller. Catacombes, vol. i., pl. xi., figs. 3, 4, 29 to 34, etc.

138:2 Mélanges d’archéologie, by MM. Martin and Cahier, vol. iii., p. 138.