Sacred Texts

Neo-Paganism

Index

Previous

p. 349

CHAPTER V

THE AMETHYST

"The February-born will find

Sincerity and peace of mind,

Freedom from passion and from care,

If they the Amethyst will wear."

Birthday Mottoes

"L'Amethiste a un lustre violet rouge, et est ainsi nommé, comme n'estant yure, aussi il resiste à l'yuronguerie . . . et profite aussi à ceux qui se veulent addonner à l'estude."--JEAN BAPTISTA PORTA, De la Magie Naturelle.

I ONCE knew a young Frenchman who affirmed that he was the only man living who knew the ancient language of Carthage--or some such town--which he had recovered from its ancient monuments. So you really can read ancient Phœnician I exclaimed in admiration. "Mais, Monsieur," was the reply. "Je le Parle." "And with whom do you talk it?" I inquired. And he replied, "Monsieur, je fais des monologues."

I ONCE knew a young Frenchman who affirmed that he was the only man living who knew the ancient language of Carthage--or some such town--which he had recovered from its ancient monuments. So you really can read ancient Phœnician I exclaimed in admiration. "Mais, Monsieur," was the reply. "Je le Parle." "And with whom do you talk it?" I inquired. And he replied, "Monsieur, je fais des monologues."

I often feel as regards all this old Etrusco-Roman folk-lore as if I had rediscovered or dug up and deciphered it, like a forgotten tongue and after all were, with my Frenchman, the only soul on earth who knew the long-buried language or cared for it, and that when I speak of it must do so en monologue. And there is a charm and a solemn beauty in the spiritual or wizard language of the olden time; and no wonder, for there was an era when it moved the world, and oracles spoke in it, and grand religions lived in it, and with them lived, in all their deep faith and many-hued gleams of glory, the Etruscan and the Roman.

And when I now and then find a flower of early faith still growing under the vile broad-leafing rank weeds which have covered all this antique garden, my heart leaps up and I begin

p. 350

to soliloquise even as I am doing now. What moved me to it was this: There is a lady in Florence to whom a nun, to whom she had been kind, sent three singular stones for a gift of gratitude, saying that she had nought else to give. As soon as I beheld them I saw that they were amulets, probably given up by some sinful penitent believer in witchcraft to a father-confessor. One was an amethyst, of no great value as a gem, but about two and a half inches in length, which has been, I think, originally a celt, and has at some later time had its edge ground off. It was probably of earliest ages; then carried by some old Roman, and so lost and found till it was given to me for a Christmas present in a red silk bag, December 25, 1891. Of the other two stones, one was a salagrana and the second a piece of antimony.

Everybody knows that the amethyst derives its name from its anti-vinous properties; for if you bear one you cannot be injured by wine. This I knew, and nothing more, till I carried the stone to my sybil and asked for a professional opinion on it. And it came in a form which subsequently startled me. I noticed as a very remarkable thing that, though she made no mention of it, she seemed to regard the stone as something personally known to her, at least by report, and that she studied it with great respect. It occurred at once to me that it was some very famous fetish which had long been lost, but of which the tradition had been preserved, like the black Voodoo stones of America. And I am now more convinced of it than ever.

"That is a magnificent amulet," she said, as if surprised, "very ancient and beautiful, This pietra avvinata--this stone mixed with wine (wine-stone)--buried and disinterred many years, must be carried to cause a good memory. Should any one wish to intoxicate you to betray you (per farci qualche tradimento), if you wear it he will not succeed. Wear it always at your side, and say:--

"'Pietra che da qualche stregone o strega

Tu sei certo stato sotterato,

Perche la fortuna ad altri non hai voluto lasciare;

Ma si vede che tu ne sei pentita

Ed hai voluto nelle mie mani farla ricapitare

Ed io sapro bene conservarla

E sempre al mio fianco portarla.

Ti scongiuro o pietra!

Scongiuro questa pietra che sempre fortuna mi voglia portare

E da ogni male mi voglia liberare'

Specialmente dai nemichi che volessero farmi

Qualche traditimento

Questa pietra mi possa liberare

E se mi volessero ubbriachare, p. 351

O con vino o con liquore,

Questo pezzo di pietra avinato sara sempre

Il mio stregone liberatore!

Ti scongiuro o pietra!'"

("'Stone, who by some wizard or some witch

Hast certainly been buried long ago,

Because thou wouldst not bring good luck to others,

Now it is plain that thou hast repented,

And hast wished to recall it unto me

And I know right well how to preserve it,

And I ever by my side will bear it.

I conjure thee, O stone!

I conjure this stone to ever bring me fortune!

And that it may free me from all evil.

Specially from foes who fain would cause me

Some deceit.

May this stone free me!

Should any wish to intoxicate me

With wine, or other liquor,

This piece of wine-stone shall ever be

My wizard, freeing me from it!

I conjure thee, O stone!'")

Now I knew that the amethyst was esteemed of old to be infallible against intoxication, or, as Baptista Porta saith: "L'amethiste attaché au col sur la bouche du ventricule (al fianco) deliure de l'yurongnerie." But I did not know that it was "good for the memory," by which my witch meant, in her simple way, as I found, also intellect and intelligence. The belief of the fortune-teller very evidently was that this famous amulet--of which there was a tradition--had been buried by or with its owner, long ago, in order that others should not inherit it, but that it had by wizard influences been brought to light again, especially for me.

I have by me about two dozen books, but was not aware that among them I possessed a treatise--De Gemmis--by Franciscus Rueus, printed at Frankfort in 1608. It had escaped me, being bound up at the end of De Miraculis Occultis, by Levinus Lemnius. And turning over my small library, hoping against hope to find something to confirm this connection of the amethyst with intellect, I found that I, by mere chance, had just the very book of all books in the world which I required. For in it there is a chapter--xi., De Amethysto--in which it is said to not only protect against intoxication, but to stimulate genius--even as the witch had declared. "Addunt et alii malas illum arcere cogitationes, et præcox felixque ingenium efficere" ("It drives away bad thoughts, and confers ripe and happy genius"). And it also brings luck; but here Rueus remembers

p. 352

himself, and declares that he will not impart the heathenish and unchristian superstitions which are reported of it--as I have done.

All of which reminds me of a story of my early days. When I was a small boy in Philadelphia, I had a Quaker schoolmaster, named Jacob Pierce, who delivered to us lectures on mineralogy, and encouraged us to make collections, giving us on every Saturday "specimens" as rewards of good conduct--in which distribution I, to my shame be it said, rarely had the first or any other choice (though it once happened to me that the rejected corner-stone which fell to my lot was the very gem of all). Being therefore a zealous mineralogist, it befell that one day on the wharf I found in the discarded ballast of stones brought by a vessel from Tampa Bay, Florida, many ammonites, among which was one which had been converted to pure chalcedony from its surroundings. With overloaded pockets I went into the office of a certain broker and banker, who, having examined my find with his friends, pronounced it to be "nothing but common oyster-shells and such-like rubbish." And after I had with pains investigated my three amulet-stones, I was told that they were in all likelihood only three common mineralogical specimens which the nun had picked up--which may, of course, be true--Italian nuns and their poor retainers being, as is well known, universally addicted to science in general and geology in particular.

The specimen prize which I got from my teacher was an amethyst, which I "traded" with another boy for an air-balloon, which caught fire while I was inflating it, and so perished. Dii avertite omen! and grant that this my amethyst--balloon of a book may soar to the skies--without burning my fingers!

May I add that the Rabbis called the amethyst achlamah, from chalam, to dream; for they believed that it attracted to its wearer marvellous dreams. And Saint Isidore compared it to the Trinity, because it hath in it three colours: firstly, purple, which is imperial, and denotes God the Father and Ruler of the world; that of violet, or humility (God the Son in His lowliness among men); and that of rose, which is expressive of love and of the Holy Spirit (vide Picinelli, Mundus Symbolic, p. 684).

Among the Egyptians the amethyst corresponded to the Zodiacal sign of the Goat (Kircher, Œdip-Ægypt, ii., p. 2). And as the goat was an enemy to vines, so the amethyst was a foe to wine.

Apropos of which citations I must, in frankness and simple honesty, remark that if there be here and there in this book some slight show of erudition--which I doubt not provokes the gently-pitying smile of many a learned folk-lorist--it is chiefly due to the girl with the wheelbarrow from whom I purchase antique lore, parchment-bound, at from a penny to threepence (this latter in cases of great

p. 353

temptation) the volume. This I take home and perfectly master, which accounts for these learned extracts. That is the way it is done. Then there is my tobacconist, who has for months past wrapped up cigars for me in leaves of the old Encyclopædie Française; or from a Latin folio of legal lore, to which I am greatly indebted. And on another occasion, when I bought two Etruscan vases for seven francs, I induced the dealer to throw in the work of Marsilius Ficinus on the Neo Platonists Iamblichus, &c. (Lyons, 1577), which edition I had been after for many a long year. And as it included the Pimander, &c., of Hermes Trismegistus (which work I copied entirely in my sixteenth year, not being able to buy it) you may judge if I was glad to get it!

THE SPELL OF THE BLACK HEN

"When thy black hen dies, thank God,

Else thoud'st been lying 'neath the sod."

"When a black hen over a miser flies

Soon after that the miser dies."

German Proverbs

In the year 1886 there was found in the belfry of a church in England a curious object of which all that could be learned at first was from the authority of an old woman and that it was called a witch's ladder. An engraving of it was published in the Folk-Lore Journal, and several contributors soon explained its use. It consisted of a cord tied in knots at regular intervals, and in every knot the feather of a fowl had been inserted.

I was in Italy when I saw this engraving, and read that the real nature of the object had not been ascertained. I remarked that I would soon find it out, which I did, and that most unexpectedly. For by mere chance, the very first Italian woman with whom I conversed, being asked if she knew any stories about witches, began with the following:--

"Si. There was in Florence four years ago a child which was bewitched. It pined away. The parents took it to all the shrines in vain, and it died.

"Some time after something hard was felt in the bed on which the child had slept. They opened the bed and found what is called a guirlanda delle strege, or witches' garland. It is made by taking a cord and tying knots in it. While doing this pluck feathers one by one from a living hen, and stick them into the knots, uttering a malediction with every one. There was also found in the bed the figure of a hen made of stuff (cotton or the like)."

The next day I showed the woman the engraving of the witch-ladder in the Folk-Lore Journal. She was astonished, and said, "Why that is la guirlanda delle

p. 354

strege which I described yesterday." I did not pay any attention at the time to what was said of the image of a cock or hen being found with the knotted cord, but I have since ascertained that it formed the most important part of the whole incantation.

This is the spell of Il Pollo nero, or the Black Hen. It is as follows:--

"To bewitch one till he die: Take a black hen and pluck from it every feather; and this done, keep them all carefully, so that not one be lost. With these you may do any evil to grown people or children.

"Take the hairs of the person, or else the stockings, and those not clean, for there must be in them his or her perspiration. Then with black and red thread sew the stockings across one another. And if you have the hairs of the person, make of them a guirlanda unita cop stoppa--a cord spun with flax or hemp--then take the feathers and si cuopre questa robba you cover (or work up) this thing in the form of a hen, and, taking the feathers, work or weave them with black and red thread into the covering of the hen, and put black pins ill the form of a cross into the hen. It must then be hidden in the mattress or straw bed of the one whom you wish to bewitch, and say:--

"'Questo pollo e maladetto,

E maladetto sia tutte

Le maledizioni la portate via,

Dal fondo del inferno,

Ma ora per una ora,

Le coma gliele voglio fare,

Che la maledizione la possa lasciare,

Et te (il nome) te la possa portare

Tu non abbia più pace!

E ne giorno e me notte!

Fino che la stregeria

Che ti io ho fatto

Non ti vengo a. levare!'"

("'This hen is accursed,

And cursed be all!

May the curses carry him away

Curses from the depths of hell

Now, for an hour

I would give him horns,

May the curse leave them on him!

And thou (the name) mayst thou bear them,

And have no more peace

Neither by day or night,

Until the bewitchment

Which I have wrought

Be removed by me!'"

THE COUNTER-CHARM-"To remove this bewitchment you must open the mattress and find the hen and wreath, and throw all that holds it into running-water.

"And then take the person bewitched, man, woman, or child, che sia, its it may be, and carry him or her Into a church while a baptism is going on, and say:--

p. 355

"'In nome di Gesu, di Giuseppe,

E di Maria la benedizione

Di quel bambino benedisca

L'anima mia!'

This the one who is bewitched must say, but if it be a child who cannot speak, then the person who carries it must say:--

"'In the name of Jesus and of Joseph,

And of Mary, may the blessing

Of that infant also bless

The soul of this child!''

Then carry it to some place near and bathe it in holy water."

This spell is considered as very terrible, and I had some difficulty in getting it. There is much curious lore connected with it, and there is every reason to believe that it is extremely ancient. In the museum (archæological) of Geneva, among the very old relics from Lacustrine dwellings, there is one of a hen, flat, knitted or felted from black hair or wool, or both, I copied it with some care, and my witch authority in Florence at once declared it to be a black hen made for magic. As it was found in water it may have been thrown there to destroy the spell, as the counter-charm prescribes. And that it is very ancient is effectively proved by the fact that other objects of the same material, and of the stone age, were found with it. This is presumptive evidence that the spell belongs to prehistoric or neolithic times.

The black hen, being an object of great fear and reverence, was worshipped by the Wends. From them it passed as a crest to the house of Henneberg (vide the Symbolik of FRIEDRICH) and to the quarterings of the Prince of Wales (Puck, 3 vols., 1852, by Dr. Bell). The gypsies in Hungary, to effect a certain cure, apply the body of a black hen to the sufferer, pronouncing an incantation. In Roumania when a Jewish girl has an affaire du cœur with the devil--or possibly with a devil of a fellow--the result is a black hen. But what is very nearly connected with this is the following: In Wallachia if a man has been robbed he goes to some sorcerer to take up "the black fast" against him. To do this the wizard must, in company with a black hen, fast for nine Fridays. Then the thief will either bring back the plunder or die. Mrs. Gerard, who gives this account, says nothing of what the ceremonies are attendant on the charm. I have no doubt that if we had the whole we should find that the Italian ceremony requires the nine Fridays' fast, and that the Wallachian Transylvanian spell is directed against any enemy, as well as a thief (vide Gypsy Sorcery, by CHARLES G. LELAND).

p. 356

One of these Italian witch-garlands was exhibited by Mr. Tylor at the Folk-Lore Congress in 1891, and I have another which was given to me for a Christmas present. It is in a box covered with red flannel. In the box was a sprig of thorn leaves. The wreath had been completed by attaching it to a small Japanese cock made of feathers.

I have found in a number of works on folk-lore and superstitions such a number of spells and incantations, of which the black hen forms the chief item, that I find it impossible to include them within the limits of this work. I may mention, however, that when I was a boy in Philadelphia, in America, once hearing that a whole dead chicken, quite dried up, had been found in a feather bed.

As feathers for beds are always picked over, I have little doubt that this object had been put into the bed by some black person as a Voodoo charm.

THE SPELL OF THE BELL

"Much the witches fear the spell,

When by night they bear a bell

Off they fly, over the sky,

When they hear dondo, dondo, dondo!"

Romagnola Song

The chief, if not the only use of bells in ancient days was to drive away demons, or dispel evil in every form; and it is very evident that they were introduced to Christian churches far more for this purpose than to call to prayer. For, as in Ireland, the church bells were generally of the size and shape of the average cow-bell of America, making no more noise than the latter. There was found not many years ago in Rome a tintinnabulum, or little bell of silver bearing magical characters, the purport of which was to avert the evil eye. I have a facsimile of this presented by the late Sir Patrick Colquhoun. And also a very small bronze Etruscan (or Roman, according to Professor Milani) bell found at Chiusi--resting on my paper as I write--and what an aid it would be here an it could speak all that it e'er has seen!

These little square old bronze Roman bells with round corners are much prized among the peasantry for amulets. In the mountain land they are always kept in one of the two small cupboards, or recesses, on either side of the chimney-piece. I have a quaint little song in the Bolognese-Romagnola dialect, setting forth the fear of the witches when they hear at twilight-tide "those evening bells."

The following from Volterra, which is given word for word, sets forth the

p. 357

manner in which the old campanologistic faith has been preserved to the present day:--

"The little bell (campanello) is held of great esteem in the Romagna, as well as in Volterra, as a jettatura, or sign against witches. When one goes out of an evening he should carry one in his pocket--ma pero bisogna che sia di bronzo e quadrato--but it should be of bronze, and four-cornered; and while going along the bell jingles in the pocket; but because it sounds there the ring is indistinct, and the witches cannot count the strokes of the clapper (quante volte pallino batte), and are thus obliged to fly, and cannot approach the bearer nor do him harm.

"Then putting it into the recess, or small cupboard by the chimney-piece (buco del cammino), repeat this incantation:--

"'Metto nel buco del cammino,

Questo campanello per tenere lontano

Pluto e le sue compagne,

Che in questa casa non si possino presentare;

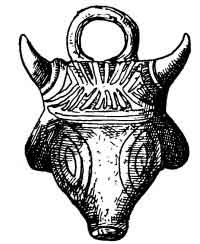

1.--ETRUSCAN BRONZE BELL, FROM CHINUSI, WORN AS AN AMULET (In possession of the writer ) 2.-OLD ROMAN MAGIC BELL

Ne in forma di cane e ne di gatto,

Ne di topo, ne di civetta,

Ne di serpe, e ne di cornacchia,

Quando alla mia casa si vengano

A presenta questa campano, suonare

E tutti maligni si possino allontanare.'"

("'In this comer of the cupboard,

I put this bell to drive afar

Pluto and his company,

That in this house they may not come,

Neither in form of dog or cat,

Nor of mole, nor of an owl,

Nor of serpent, nor of crow

Should they come into my home,

May the bell ringing drive the wretches away!'")

p. 358

Pluto--not Satan--here appears as leader of the witches. I have observed that the further we get from the Romagnola mountains into the plains, the more do the Roman gods appear. The shoemaker who gave this incantation had, however, some tincture of letters, having studied and read. Pluto may be a survival, but he is gently doubtful. But as I would not deprive a dying god of his very last chance for life on earth, I add that subsequent inquiry removed this dire suspicion. Pluto still lives. It may be noted here, by the way, that the belief that bells ring of themselves, and that chains rattle, to announce the presence Of spirits, is of old Roman origin, as I find confirmed by Maffei in his Magica Distrutta--a work in which the author rides full tilt at the windmill of sorcery, utterly annihilating it, but never perceiving that he also destroys with the same lance another black spectre known as la Santa Fede Cattolica, or La Chiesa Apostolica, all of whose marvels and miracles came out of the same old tub. Think of this, O friend, when, in some darkened and gloomy hour, you are in church and hear the padre ring his little bell, and let a happy thrill of heathenism pass at the sound through your heart!

Not only bells, but trumpets and cymbals were used to drive away demons--which reminds me that few know whence came the idea of the last trump at the Day of judgment--

"Tuba mirum spargens sonum,

Per sepulchras regionum,

Cogens onmes ante thronum."

It is the great blast to be blown at the death-bed of a dying world, and was derived from a heathen source, as is set forth in the following passage from the same Arte Magica Distrutta of Maffei (17 5 7):--

"There was a strange religious ceremony which the Gentiles observed when dying. This was to play (luring the last agony on the horn, or trumpet, or instruments of metal, and of great noise. The motive to this was doubtless the belief that it drove away larve (demons) which, as it was believed, hated the sound of metal, which vulgar opinion is set forth by Lucian in Philops. The Dire were witches who flew through the air, concerning the driving away of whom by noise Pliny writes (1. 28, c. 2). Eusebius tells us that demons were driven away by the sound of timpans."

[Timpani are tambourines, and it is an awfully curious thing, by the way, that when bees swarmed these timpans were anciently used, and that tin pans are now beaten in their stead.]

That bells have souls, wills, and ways of their own is apparent from the number of marvellous instances recorded of their having rung of themselves without any human aid--as they did at the death of Von Rodenstein--albeit

p. 359

Prætorius, who devotes several pages to this important subject in his marvellous and rare Glückskopf (1669), suggests that it may have been done by a Poltergeist, which is a spirit much given to noise and mischief, and which makes its appearance, in my belief, very often in the form of a medical student, but always as a youth.

Remains to be remarked that the little bronze bell is supposed to be a fairy lady--as her form suggests--and is the more human as having a voice. Which fancy did not escape the monks, who addressed them as saints, as you may read in the chapter on Bells in Southey's "Doctor":--

"Bellula bella, mi puella:

Tu me corde tenes!"

THE SPELL OF THE BOILING CLOTHES

The reader must not suppose that the charms, incantations, and devilments of different kinds which are here solemnly confided to him, are known to the multitude. Many have, it is true, leaked out; but most of them are secrets rich and rare, treasured up among the elect who, dying, leave them as a rich legacy unto their issue. This was recalled to me by a curious incident alluded to in the preface. Firstly, I pray you read the following, as taken down four years ago--in 1888--from a witch:--

"Quando si ha uno bambino stregato ("When a babe is bewitched"). Take the clothes of the child, and put them in a pot to boil at midnight. All the garments must go in, with shoes and stockings. Then take a new and very large knife, and sharpen it at a table, and say, sticking it in the table:--

"'Non infilo questo coltello

Ma infilo la maladetta strega

Che non viene! Che non viene!

Non possa resistere

Sinquando in mio bambino

Il salute non lo fa ritornare!'

("'I do not sharpen this knife,

I whet the accursed witch,

That she cannot resist coming

Until unto my child

She again restores health!')

"Then the witch will appear at the window--it may be at the door--in the form of a cat, or dog, or some form or spectre. But be in no fear, for these are but shifting forms (forme cambiate), and do not take the knife from the table nor let the clothes cease to boil till three o'clock.

"And being by this charm compelled to come and obey, the witch will remove the illness from the child."

p. 360

In the Secolo of Milan, which has by far the most extensive circulation of any journal in Italy, there appeared, March 3, 1891, the following account of a serious and very singular disturbance:--

"A Mediæval Scene at Porta Ticinese

"We seem to dream, and yet this which we relate occurred yesterday morning here in Milan, and it is true in every one of its startling and shocking details.

"In the Via Ripa Porta Ticinese, No. 61, in a modest room on the fourth floor, dwelt the family of a journeyman varnisher, Malaterra Franciusi and his wife, Virginia, aged twenty-five, a glove-maker, with two children, one of which has been ill for a month with some unknown, obstinate, and strange disorder.

"A neighbour of the Franciosis, a woman who pretended to some knowledge of medicine, declared that the child was bewitched; that it would be quite useless to have recourse to physicians and priests, and that the only way to cure it would be to discover the sorceress who had made the mischief. But how was it to be done?

"The woman, as a great secret, after much entreaty from the Franciosis, taught them how it was to be done by putting the clothes of the child into a pot with water and boiling them. She declared that at the instant of the boiling, the witch would be drawn to the place by an irresistible diabolical force, and thus compelled to make herself known. This war, done, and the clothes put in the pot and the pot on the fire.

"By mere chance, just as the water began to boil, a woman entered. This was one Angela Micheletti, thirty-four years of age, seven months gone with child. She was the wife of a labourer. Being a friend of the Franciosis, and on her way with a pair of wooden shoes to have them mended, she dropped in to inquire as to the health of the child.

"At seeing her the mother screamed 'Dalli alla strega!' ('Give it to the witch!') La Micheletti, thinking that her friend had gone mad, tried to calm her, but the other, more exasperated, howled with all her force, 'Aiuto! La strega!' ('Help! the witch!') La Micheletti fled into the street.

"In an instant a great crowd had assembled, who, hearing the cry and accusation, all set upon La Micheletti as if she had been a mad dog, per lacerarla à brani--seeking to tear her to pieces. So she fled, pursued by the mad mob, crying, 'Dalli alla strega!' The poor creature, more dead than alive, took refuge in the church of Santa Maria del Naviglio, but the crowd rushed in, and while she knelt before the grand altar, raising her hands in supplication, weeping and screaming for mercy, her hair was literally torn from her head and divided among the women who attacked her, and then she was very cruelly beaten. The parocco, or parish priest, tried to shield her, but in vain, and he himself escaped narrowly from being knocked down.

"The poor victim was then carried, amid all abuses and curses, from the church, and haled along to the room of the Franciosis. Here was another savage scene. La Micheletti being required to disenchant the child, to which she replied asserting her innocence of all such evil, and received howls, curses, and blows.

"Finally the Delegate, Sig. Omodeo, succeeded, with some military police and with great trouble, in dispersing the mob. Then the woman Franciosi, convinced too late of her unpardonable folly, fell on her knees before La Micheletti exclaiming, 'I am not to blame; I was advised to do so by another--I was blinded by love of my child!'

"In the afternoon the poor Micheletti, accompanied by her husband and Sig. Omodeo, was taken home in a brougham and put to bed. This morning she was better but still trembling from her terrible experience. The sad impression of this savage mediaeval scene will long be remembered in the suburb of Porta. Ticinese.

"The women who tore the hair from the head of La Micheletti, went to their homes and burned it, pronouncing incantations, and than ran to the room of the Franciosis to see if the child was cured. And as they declared they had found It somewhat better, they cried, 'Ecco se non è vero ch'è stata stregata!' ('See now, if it is not true that she is a witch!')"

p. 361

Sometimes gloves or stockings alone are boiled for certain peculiar "points" in bewitching. Of the burning of hair to remove bewitchment I have elsewhere spoken. But the real moral meaning of this horrible story will not appear at once as it should to every reader. It is this: It was all very well for the parocco, or parish priest, to try to shield the woman at the altar, &c., but had that priest ever in all his life once told the people that there is no such thing as witchcraft, and that it is all delusion? Did any priest in Italy, or any of the Catholic teachers whose duty it is to enlighten their flocks, ever tell them plainly that there is no such thing as sorcery. No; of course not. For that would be to attract doubts as to the truth of their own peculiar sorts of sorcery, incantation, and magic--just as the small American boy, who, when informed by his father that there was no such Christmas spirit as Santa Claus, asked reproachfully, "And have you been playing it off on me in the same way about Jesus too?"

The Church at Rome does not deny the existence of modern witchcraft and sorcery. There are three, and I know not how many more, Roman Catholic books written to prove that all the mighty miracles of modern spiritualists, such as carrying cigarettes to secret places, playing banjoes in the dark, and bringing penny bouquets from Paradise, are all done by the devil, and these books have been licensed and approved by the Pope. Can anybody imagine that if these Milanese had been Protestants they would have acted as they did? By their fruits shall ye know them!

Now in all such superstition Milan is as light to darkness compared to our Florence, and Florence in this respect is the same in relation to the Toscana Romagna.

I have also from Peppino, the youth frequently alluded to, a long and detailed account as to how quite recently, a child which was dying in the village of Premilcore in the Romagna Toscana, was saved by boiling its clothes and saying:--

"Diavoli tutti

Del inferno scatenatevi,

Tutti e fate venire,

La strega del mio bambino,

In mia presenza. Sia!"

Then the witch appeared, and by casting the usual gomitolo, or skein, into the air, the child was cured. Then the witch was taken by two other witches into the fields and rolled unmercifully over the ground till she lost all her power of witchcraft.

p. 362

RING SORCERY

"A droite l'anneau presage

Prompt et heureux mariage,

A gauche il figure:

Abandon, rupture."

Le Jeu de Cartes de Mlle. Lenormand

Divination by means of rings was well known to the early Romans, and is thus described (Trac. Magicus, p. 92): "Dactylomantia divinat annulis ad certam cœli posituram constructis vel incantamentis, et super tripodem ad certa verba motis" ("Dactylomancy is divining by means of rings made at certain planetary conjunctions, or with incantations, and moved on the tripod with certain words"). For tripod read tambourine, and for rings any small objects, and we shall have one of the most ancient forms of divination in existence. These small objects are, among the Hungarian gypsies, seeds of the deadly thorn-apple; in Lapland, the small image of a frog.

In modern Italy there is another kind of ring prophecy. It is, however, very ancient, and is known in many countries. Take a bowl, or vase, or cylinder, divide its inner edge into so many parts as there are letters of the alphabet.

Take a gold, or any other ring, and let it be consecrated. (Consacrasi l'anello prima dell operazione.) Then tie a thread to it and hold the end of the thread in the right hand and a sprig of verbena in the left. Let the ring hang in the cylinder. According to one authority the thread should be wrapped round the thumb and pass over the pulse so as to secure the right vibration. Then ask a question and the ring will begin to swing, and strike on the letters and spell out the reply.

As I have said, this is a very ancient species of prediction or invocation. It is the same in principle with the planchette, but requires only one operator. It may be observed that when the person who holds the thread is deeply in earnest, or believing, and has prepared himself to work the oracle by serious reflection, the replies spelled out are often very remarkable, not to say startling, and whether produced by involuntary mental action or by external causes, they are in most cases curious. I have met with the assertion that by means of the thread and ring

p. 363

one can always ascertain exactly what o'clock it is when the edge of the cup is divided in twelve parts. "How would it be where the day is divided into twenty-four hours?" It would be just the same, and true answers would be often given, because the action is subjective, or comes from the operator.

Another variety of this kind of divination is to place an evenly balanced rod, or needle like that of a mariner's compass, on a pivot, in the centre of a plate. Around the edge, in circles, are letters and numbers. This is a kind of roulette. Give the bar a turn and when it ceases revolving observe the letter or number opposite which it stops.

Again, take a round, flat surface, say a wooden plate surrounded by a border half an inch in height. This surface is covered with numbers and letters. Then take a ring and spin it as one spins a coin. We draw conclusions from the letters, &c., on which it falls.

Apropos of roulette and the ancients there is at Homburg les Bains a collection of ancient Roman remains, and in an adjoining room the roulette table which was last used in 1871. Two or three of the average class of English, or American, tourists, being shown through the collection, cried, on seeing the wheel, "And is that old Roman, and did the Romans play roulette! How interesting!" For the truth of which I vouch "with both hands," having heard it.

An ancient ring which has been long worn is said to be the best for divination. I have one of silver with the image of a toad cut in hæmatite in it, about four hundred years old, which has, I doubt not, been frequently tried in spells. Also a silver and enamel messenger ring which once belonged to King Roger of Sicily, which, if it could tell all it ever witnessed, might describe the story of Schiller's Diver.

AMULETS, OMENS AND SMALL SORCERIES

I include in this chapter certain odds and ends of folk-lore which are not without interest. The first which I shall give is the pine-cone.

"Take a pine-cone, after all the pinoli (nuts or seeds) have been removed. Then on every scale, or within it between the scales, put a lupine (dry). Then take a flower-pot and fill it with fine earth, and plant the cone in it quite covered with earth or buried. Put it out in the air, and water it like any flower. Should it grow well and look prettily it is a sign that all things will go well with you. But its growing badly is a bad sign. But you must always keep it by you to secure the good luck, and even carry it with you when you travel, And to maintain the principle (bisogna tenere la sistema) you should plant a new cone every year."

American young ladies have a somewhat similar oracle in the sweet potato which also makes a very pretty fortune-teller, If it flowers or leaves well, it is a

p. 364

sign that the owner will be magnificently dressed on her wedding-day, and have a grand festa, which, I suppose, will be "in all the papers." Apropos of this very small gardening, it may be mentioned that since Roman times, all d perhaps much earlier, the planting of cress, mustard, or seeds of any sort to divine luck by their growth, has been common in all countries. One very easy form is as follows: If you keep a bird--say a canary--get an empty box, a raisin box, eighteen inches or two feet in length, fill it with earth and hang the cage over it. Throw into the earth the cleanings of the cage and a few canary or hemp seeds. These will soon grow, and when sprouting or about all inch high will be devoured by the bird with avidity. This is very lucky for the canary.

Very old keys are good amulets for luck. They may be carried in the pocket or hung up by a red ribbon in the room. And it is very lucky to find one. While picking it up you should say:--

"Non prendo questo chiave l'ho trovato.

E lo porto con me, ma non porto

La chiave pero la fortuna

Che sia sempre appresso di me.

("'Tis not a key which I have found

Nor one which I shall bear around,

But fortune which I trust will be,

Ever my friend and near to me.)

"And this may be said for anything else which is found."

The special meaning of the key is success with women, the word key (chiave) being applied to the virile organ, and chiavare, "to key" to the act of copulation. Its general signification as an omen is success in your next undertaking. Thus to dream of a key or see one is a good sign:--

"La clef près de ta main

Annonce qu' à la fin

Tu auras du succès

Dans tes derniers projets."

If you blow or whistle in a key, especially an old one, it will call to you spirits or fairies, who will be favourable to you and aid you, in love above all things.

We can divine with keys in several ways. By locking a padlock when a couple are married, one can stop all intimacy between them. But it is with the sieve that Master Key becomes a great sorcerer, as was once set forth in the St. James's Gazette:--

p. 365

"Methods of discovering the names of thieves and the whereabouts of stolen goods were endless; and many an old hag, down almost to our own time, has driven a profitable trade with 'infallible' means of divination as old as the fire-worshippers. The formulae most frequently used for these purposes were known as 'the key' and 'the sieve.' The name of the suspected person was written upon a piece of paper placed around a key; the key was tied to a volume of Scripture, and the whole suspended by a cord spun for the purpose, from the finger of a young unmarried woman. Three times she repeated in a low voice the verse 'Exurge, Domine'; and if at the words the key and the book turned, the guilt of the suspect was proved. If neither of them moved his innocence was clear. Divination by the sieve was long in high favour, for this was deemed to be the most certain of all methods. Hence, says Erasmus, the proverb 'To divine with the sieve'--to express the certainty of a thing. A sieve was suspended from a pair of scissors held by two assistants. The operator, having pronounced the name of the suspected person, repeated a shibboleth consisting of six words--dies, mies, jesquet, benedoe, fet, dovina--'which neither he or his assistants understood.' If the person whose name was mentioned were guilty, the six magical words 'compelled the demon to make the sieve spin round.' Pierre D'Abanne--the author of a most entertaining manuscript work on the elements of magic, preserved in the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal 1--recounts that he used this method three times with the most complete success, and then gave it up; fearing that the demon, in revenge for having been compelled to tell the truth three times in succession to one man--greatly, no doubt, to his chargin, since he is by nature a liar--would draw his tormentor into toils from which there would be no escape.

Never pass by a coin, however trifling; should you let it lie your luck will pass to the person who finds and takes it. But on picking it, up repeat the same lines.

"To know the future or how any event will end, or what your luck will be in a lottery: Take a dry poppy-pod, make a hole in it, shake out the seed and place in it a paper on which your question is written. Then put it beneath your pillow and repeat:--

"'In nome del cielo, delle stelle, della luna,

Fate mi face il sogno secondo . . . (le mie intenzione).'"

("'In the name of heaven the stars and the moon!

May I dream and that full soon,

If this I see . . . (here repeat your wish).'")

The poppy was not only sacred to the god of dreams and of sleep, but owing to the immense number of its seeds was a type of fertility and wealth. Hence the gilt poppy-heads, so commonly seen in the apothecaries' windows, which are or were originally amulets to bring money.

Another amulet allied to dreaming is made by taking twigs or bits of small boughs from an oak-tree (in England of mountain-ash). Bind two of these so as to make a cross, or lay them across one another on the table, or stand, by your bed, and repeat before going to sleep:--

"Non metto questa quercia,

Ma metto la fortuna,

Che non possa abbandonar'

Mai la casa mia."

p. 366

("'Tis not oak which here I place,

But good fortune--by its grace

May it never pass away,

But ever in my dwelling stay.")

The sticks should be bound with red ribbon (woollen), and the cross thus formed and spelled becomes an amulet which may be hung up to bring good luck or drive away misfortune.

Whenever one puts on a new garment, he or she should repeat this spell:--

"Porto questo vestito

Per maggior fortuna

Sia maladetto, maladetto sia!

Chi cerca nella mia vita

Di portar qualche malia!"

("This coat I wear, this garment bear,

To bring good luck to me;

If any man begrudge that luck,

May he accursed be!")

Should you find, or pick up, or even see any object, you may divine by it what is to happen. Thus if the first bit of ribbon, or string, or cloth which you find is of any colour, especially if it be new and fresh, it will portend:--

Red (especially scarlet)--Good fortune, prosperity, successful love.

Yellow--jealousy; according to some, gold.

Grey--Peace, calm, content.

Silver--Disquiet, disturbance, passion, pain.

Gold--Fortune, prosperity, gain, intelligence.

Black--Vexation, discontent, trouble.

Orange--Misfortune.

The belief in the magic virtue of red, especially of red wool, is as general in Italy as it is ancient. As it is the colour of the blood and of fire, it is sacred to life and heat. So a red ribbon or cloth hung from a window or over a bed brings luck.

"When one sees a very fine large butterfly, catch it as carefully as you can without hurting it, and look under its wings, for there you may often find characters which indicate winning numbers in the lottery, or Yes or No to a question. Then let it go again, for your luck will depend on not injuring it. And this is the case with serpents or any animals which are marked, for there is writing in all things if we can but read it."

To find a horse-shoe is as lucky in Tuscany as it is elsewhere. Hay is also luck-bringing, If you find a horse-shoe, make a red bag and put the horse-shoe

p. 367

into it with hay, and it will be an admirable amulet. It is to be kept always in the bed.

"If a youth loves a maid he will do much to win her affections should he give her amorino, that is mignonette."

In this case we can infer that nomen est omen.

Shoes or gloves when boiled in water yield a liquid which if not palatable is however of great use in witchcraft, though I am not informed as to the exact manner in which this soupe au shoe is served up. 1

When children see a lucciola, a fire-fly, they sing a strange little song which is also an incantation for luck:--

"Lucciola! Lucciola.

Viene a gara!

Mette la briglia

A la cavalla,

Mette la briglia

Al figluolo del re,

Che la fortuna

Venga con me,

Luciola mia

Viene da me!"

("Fire-fly! O Fire-fly!

Enter the course;

Come, put the bridle

Now on the horse!

Come, put the bridle

On the king's son,

So that good fortune,

By me may be won!

Fire-fly! O Fire-fly

Make it my own!")

When a woman has a sore throat (effeto di lu gola abassata), she must take her own apron and measure or fold it in a cross thrice (misuararla in croce), for three mornings in succession. Then when she has done this she must, before eating, put three pins crossed with a sharpened knife stuck into the table and say:--

"Diavolo, vi discongiura!

In carne ed ossa,

p. 368

Si questa donna e stregata

Questa strega tenerla stregata,

Più non possa,

Sinoquando questa donna non guarira

Questo coltello del tavola non sortira

E cosi la strega più pace non avra!"

("Devil, I conjure thee alone,

In flesh and in bone!

If this woman bewitched be,

The witch at once shall set her free

Till she's freed from all her pain

The knife i' the table shall remain,

And the witch shall feel the knife

In her soul and in her life!")

This is interesting as indicating the Shamanism according to which every pain or the least disorder is supposed to be caused by sorcery--a doctrine which exists in full force in another form known as Prayers for the Sick.

Egg-shells are witches' goblets for drinking. Therefore lest they use them for such, one should after eating an egg break the shell to fragments, and throw them into a running stream and say:--

"Se sei una strega

Va al diavolo,

Che tu porta via

Assieme call' acqua corsia!"

("If thou art a witch,

Go, O devil's daughter!

And be borne away

On the running water!")

It is commonly said that--

"Spilling or dropping wine

Is a very lucky sign;

But spilling or dropping oil,

Much good luck will spoil."

However, when the wine upsets, some think it is witch-work, and so they put the palm of the hand in the wine, and then strike it on the forehead and say, making the sign of the cross:--

p. 369

"In name del cielo,

Delle stelle e della luna!

A chi me ha data il malaugurio,

Me lascia la buona fortuna!"

("In the name of heaven,

Of the stars and moon;

May the one who gave misfortune,

Bring me better luck and soon!")

But that, vin repandu porte bonheur, is a very old belief It forms the theme of an old Norman-French fabliau. There is a very curious custom observed in La Romagna, which was thus described:--

"When it has not rained for a long time and the fields are dry, they take stones and roll them through the field and say:--

"'Queste pietre voglio rullare,

Ma non rullo le pietre,

Rullo le pietre, rullo l'acqua

Che in terra possa venire,

Ed i campi mi possa umidire,

E cosi buona raccolta possa venire!"

("'I wish indeed to roll this stone,

And yet it is not it alone,

I roll the stone that water may

Come in these fields so dry to-day,

And water well the thirsty field,

So that it may good harvest yield!"')

PRELLER states (Rom. Myth., p. 312) that in the temple of Mars there was kept a great stone cylinder which, when there was a great drought, was rolled by his priests through the town. And we know that such an application of similar stones was common in Italy in dry seasons, especially in the country. And LABEO in his work on the Etruscan books of ritual, writes: "Fibræ jecoris sandaracei coloris dum fuerint, manales tunc vertere opus, est petras, id est quas solebant antiqui in modum cylindrorum per limites trahere pro pluviæ commutanda inopia." Traces of the custom are found in other countries.

As among the Romans, the picture of a bunch of grapes, rudely painted, is placed in vineyards in Northern Italy, as an amulet to secure a good crop.

There are many curious ideas current as to old Roman and Etruscan relics, which are, however, generally supposed to be connected with ancient sorcery. On this subject I obtained the following very curious information:--

"When a woman is incinta, or enceinte, she should not look at animals, and especially beware seeing those figures depicted or set forth in bronze, leather, or cloth, which are half animals and half men, with heads

p. 370

like goats and legs of Christians (col capo di capra, e le gambe di Cristiano), or faces with the legs of devils, like those of a horse (i.e., Pan and the sylvan gods).

"If a woman at such a time looks at these it may easily happen that she will have a son like them, for it may come to pass in such cases that he will be born in similar form and so easily become a wizard."

That is, the old latent sorcery will pass to the child and be developed in it. The images here referred to are mostly the old Roman bronze figures of rural deities or lares, which are so frequently found in schiavi, or excavations. Among these are many ex voto offerings, the same in nature with the little figures of wax so common in Catholic churches. It is worth observing that the ancients went to much greater expense in such marks of gratitude for divine aid than do modern Catholic Christians. Bronze was dearer then than wax is now, but it was quite as freely employed by the faithful.

Certain spells are used in Tuscany with a double meaning, that is to say, they are employed either to injure a certain person, or else to defeat an evil witch, or to break a spell or cure a disease. Among these are the following: A plant or herb, having had an incantation pronounced over it (nearly the same in form with several which I have given) is left to wither, the belief being that, as it fades, the person or disease or enchantment will slowly die or vanish. Again, an apple is cut to pieces--a common form of magic--or an orange or lemon is stuck full of pins and left to dry up, with the same consequences. Also a stick is broken, which is similarly a formula known in the West where it has become a legal form, or else a piece of woollen felted or woven cloth is pulled apart. All of these spells are very ancient and may be found in certain conjurations, given in Lenormant's Magie Chaldaïenne, for which they were translated from Accadian cylinders. The author remarks that while pronouncing them the operator had to perform certain conjurations resembling those described in the Pharmaceutria of Theocritus and in Virgil's VIII. the Eclogue, which are also essentially those now in use. The Assyrian incantations are as follows:--

I

As this plant withers, so shall also the spell!

The burning fire shall devour it!

It shall not be arranged on the lines of a vine arbour;

it shall not be trained into an orchard, an . . .;

the earth shall not receive its root;

its fruit shall not grow, and the sun shall not smile upon it;

it shall not be offered at the festivals of kings and gods!

The man who has cast the evil fate, his wife,

the violent operation, the finger pointing, the written spell, the curses, the sins, p. 371

the evil that is in my body, in my flesh, in my bruises,

may [all that] be withered like this plant!

May the burning fire devour it this day!

May the evil fate depart and may I behold the light again!

II

As this fruit is divided into pieces, so shall also the spell be!

The burning fire shall devour it;

it shall not return to the supporting branch from which it is cut off;

it shall not be offered at the festivals of kings or gods!

The man who has cast the evil fate, his wife,

the violent operation [i.e., evil invocation], the finger pointing, the written spell, the curses, the sins,

the evil that is in my body, in my flesh, in my bruises,

may all [that] be divided in pieces like this fruit!

May the burning fire devour it this day!

May the evil fate depart, and may I behold the light again!

III

As this twig is plucked up and broken in pieces, so shall also the spell be,

The burning fire shall devour it!

its fibres shall not again unite themselves to the trunk;

it shall not arrive at a perfect state of splendour!

The man who has cast the evil fate, his wife,

the violent operation, the pointing with the finger, the written spell, the curses, the sins,

The evil which is in my body, in my flesh, in my bruises,

may [all that] be broken in pieces and plucked up like this twig!

May the burning fire devour it this day!

May the evil fate depart, and may I behold the light again!

IV

As this wool is rent so also shall the spell be,

The burning fire shall devour it!

It shall not return to the back of its sheep;

it shall not be offered for the garments of kings and gods!

The man who has cast the evil fate, his wife,

the evil spell, the finger pointing, the written spells, the curses, the sins,

the evil which is in my body, in my flesh, in my bruises,

may all [that] be rent like this wool!

May the burning fire devour it this day!

May the evil fate depart, and may I behold the light again!

Like unto this are two other incantations, one applied to rending a banner, the other to tearing up a piece of frilled stuff. I call attention to the fact that these are so strikingly like the modern Tuscan both as regards subject, spirit, and general treatment, that the burden of disproof in reference to a common origin should in common sense fall on the sceptic. These Chaldæan cylinders speak of seventy-seven fevers--i.e., all diseases--as coming from the seven primary demons of disease. The Bogomile Slavonian heretics of the fourteenth century also recognised

p. 372

the seventy-seven fevers and had an exorcism for them. And in an old German spell current in Pennsylvania we have as a cure for fever the following:--

"Good-morning, dear Thursday! Take away from--the seventy-seven fevers! O thou dear Lord Christ, take them away from him. . . ."

In the Chaldæan incantation against the plague (i.e., the seventy-seven personified) the operator must turn his face towards the setting sun. In the German spell he must not speak to any one till after sunrise, which involves the same idea.

It is very remarkable that all over the world a black pebble of kidney shape is supposed to be one of the most powerful of amulets. At the Folk-Lore Congress of 1891, such stones were exhibited from widely different countries. I myself possess one which was brought from Missouri and presented to me by Miss Mary A. Owen, to which most extraordinary value and reverence was attached by the black Voodoos and their disciples. It had been kept with the most jealous care for many generations in the families of these sorcerers, and came originally from Africa. To become an ordinary Voodoo, the postulant must fast and watch, undergo revolting penances, and cultivate "power" and "will" all his life. But the possession of an authenticated "cunjerin'," or conjuring-stone, renders all this unnecessary, the owner by the mere act of possession becomes a grand past-master Voodoo, or multote, and requires no further initiation. Even the chief black sorcerer in Missouri, or the king, has never been able to get one. 1 It would be useless to attempt to palm off a similar black pebble for a real one, since it is said that there are in all North America only six-or rather five, mine being one of the half-dozen--and their possessors are all well known, as is every mark in the stones. Black believers have been known to make a pilgrimage of a thousand miles to be touched with this marvellous stone--or to hold it in the hand. I hold it in my left hand as I write, mildly trusting that I may thereby charm, or at least interest thee, O reader. It must, like all Voodoo amulets, be carried in a wrapping, or a bag, which may be closed by wrapping a string round. it, which must not, however, be tied, as that would prevent the free egress or ingress of the spirit which dwells in it. Once a week it should be dipped in, or touched with, whiskey, but I am assured that eau de Cologne will answer just as well, which it surely ought to do, since the recipe for it was given by an angel to Saint Elizabeth of Hungary.

p. 373

LEAD AND ANTIMONY

"Talismani erano pietre, o gemme co pezzetti di metallo . . . in forza di quale si credeva avessero straordinarie virtú, e singolari, ma la frequenza loro, e il credito venne da' Gnostici, e da Basilidiano, de quali assai parla nel suo libro, santo Ireneo."--Arte Magica Distrutta, MAFFEI, 1757

"Non solùm verò in plantis quæ vestigium habent vitæ, sed etiam in lapidibus aspicere licet, imitationem et participationem, quandam luminum supernorum."--Proclus de Sacrificio et Magia (Interpre MARSILIO FICINO), LUGDUNI, 1577

A piece of lead ore is supposed to possess peculiar virtue as an amulet against malocchio, or to bring luck. Of these I have seen three, two of which I possess, with the invocation which must be pronounced when one is tied up in the usual red woollen bag. Far more potent, however, are the old Roman sling-stones, or pointed slugs of lead, of which such numbers are everywhere found, and of which I have two, which I bought for a half-franc each, as talismans for the evil eye. But more effective still is a lump of crude antimony. This is supposed

ROMAN SLING-STONE

to also contain zinc and copper, which give it great power. For these I have also the scongiurazioni, which are as follows. I believe them, however, to be imperfectly recalled:--

"Antimonio che sei di zingo e di rame:

Il più potente ti tengo sempre con me,

Perche in mi alontani le cattive gente,

Da me alontanera,

E la buona fortuna a me attirerai!"

("Antimony, who art of zinc and copper!

Thou most powerful, I keep thee ever by me,

That thou mayest banish from me evil people,

And bring good luck to me.")

That for lead was obtained for me, written in the following words, verb. et lit.:--

"Antimogno che di piombo sei

Non ai la stessa forza della zingo e rame,

Ma prestati per la forza che in ai

Tutte le chattive persone da me alontanerai

Ela buona fortuna mi attirerai!"

p. 374

("Thou antimony, who art lead,

Not having the force of zinc and copper,

But grant that by the power which thou hast,

That thou wilt keep all evil people from me!")

It will be observed that in both of these invocations great stress is laid on the virtue of copper, which is probably derived from the old Roman religious feeling regarding it, as the "body" of bronze. But after much weary inquiry, owing to the difficulty which my informant had to put her ideas into form, I elicited these ideas: "The metals have all their occult virtues and their light--that is, their lustre--when broken; deep in the earth, and in darkness, this light still shines in itself; it is a light dreaded by evil beings. Copper and gold have the reddest light; this is the most genial, or luck-bringing; and copper is supposed to form part of antimony. Antimony is stronger than lead, because it consists of three metals, or rather always has in it copper and lead."

There is strong confirmation of this theory in Cardanus (De Rerum Varietate, xvi., 8, 9) and Peter of Aries (Sympathia septem metallorum et septem selectorum lapidum ad planetas. Paris, 1711), or as it is set forth by Nork in his Etymologisch-symbolisch-mythologisches Realwörterbuch:--

"What the stars are in the nightly heaven, that are the gleaming metals in the dark abyss of the earth, therefore it is intelligible that those earthly gatherers of light should be associated with the heavenly ones, and as the worship of light was concentrated in the sun and planets, so unto every leading planet there was assigned a glittering metal according to its degree of radiance."

This is also curious since it suggests the source whence Novalis drew his famed simile that miners are inverted astrologers, reading in the earth the past, just as other seers read in the heavens the future. And it seemed to linger quaintly in the fancy that copper and antimony and lead have all their "light" and magic mystic power.

A few days ago I bought in an old shop an amulet of lead ore in which a piece of copper was embedded. This was, as the American negroes say, "a mighty strong cunjerin' stone." So I purchased it for a franc--the bargain including two little old bronze Etruscan images, one of Aplu and the other of god Nosoo, or the deus incognitus.

Apropos of this shop, it was one where the prezzi fissi principle was carried out, that is, of fixed prices marked on the wares. This does not mean at all in Italy that a dealer will not take less, but that he binds himself not to take any more. The price is convenient as giving a basis for a bargain. Its being "fixed," according to the Italian idea, is that the piece of paper marked is "fisso," i.e., fixed,

p. 375

or stuck on the article indicated. Now this young man had the first volume of the Museum Etruscum of Antonio F. Gori, 1737, marked "ten francs," but seeing that I wanted it he offered it for eight.

"Throw in that fourteenth-century Virgin on a panel, with a gold background," I said, "and it's a bargain."

So the Madonna was thrown in in a hurry--she was really well worth about tenpence--and we were all satisfied.

This was indeed--as the French advertisement in a shop for the sale of Roman Catholic "idolatries" announced--"une Vièrge d'occasion." I may here mention that these are the only kind of pictures which I ever buy; in which I very much resemble a young gentleman of my acquaintance who only admires ladies with large fortunes. All of his madonnas, like mine, have gold backgrounds.

The picture was fearfully dilapidated, but with gesso and gouache colours, and white of eggs, and gum, and gold, I restored it so that it seems better than new for it looks every whit of its four hundred and fifty years, or even older. But then the surroundings are favourable to such work--for Florence is a famous place for rehabilitating damaged Virgins--and I have heard some marvellous stories about such rifatture--which I omit for want of space.

p. 376

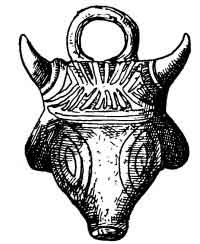

BRONZE ETRUSCAN AMULET AGAINST THE EVIL EYE

(In Possession of the Author )

Footnotes

365:1 It has been several times published; the last edition is by Scheibele of Stuttgart (in his Kloster).

367:1 In Voodoo if a woman gets another's shoes which have just been taken off, and takes off her own and laces them inside the other pair, and so leaves them till morning, the man is sure to fall in love with her.--Note by MARY A. OWEN

372:1 This remarkable man who was known as "King Alexander" died while this work was being printed.

I ONCE knew a young Frenchman who affirmed that he was the only man living who knew the ancient language of Carthage--or some such town--which he had recovered from its ancient monuments. So you really can read ancient Phœnician I exclaimed in admiration. "Mais, Monsieur," was the reply. "Je le Parle." "And with whom do you talk it?" I inquired. And he replied, "Monsieur, je fais des monologues."

I ONCE knew a young Frenchman who affirmed that he was the only man living who knew the ancient language of Carthage--or some such town--which he had recovered from its ancient monuments. So you really can read ancient Phœnician I exclaimed in admiration. "Mais, Monsieur," was the reply. "Je le Parle." "And with whom do you talk it?" I inquired. And he replied, "Monsieur, je fais des monologues."