Sacred Texts Legends & Sagas Celtic Index Previous Next

THERE was at some time a young king in Eirinn, and when he came to man's estate the high counsellors of the realm were counselling him to marry; but he himself was inclined to go to foreign countries first, so that he might get more knowledge, and that he might be more instructed how the realm should be regulated; and he put each thing in order for matters to be arranged till he should come back. He staid there a while till he had got every learning that he thought he could get in that realm. Then he left Greece and he went "do'n Fheadailte," to the Italy to get more learning. When he was in that country he made acquaintance with the young king of "an Iubhair," and they were good comrades together; and when they had got every learning that they had to get in Italy, they thought of going home.

The young king of the Iubhar gave an invitation to

the young king of Eirinn that be should go to the realm of the Iubhar, and that he should stay a while there with him. The young king of Eirinn went with him, and they were together in the fortress of Iubhar for a while, at sports and hunting

The king of Iubhar had a sister who was exceedingly handsome; she was "stuama beusach," modest and gentle in her ways, and she was right (well) instructed. The young king of Eirinn fell in love with her, and she fell in love with the young king of Eirinn, and he was willing to marry her, and she was willing so marry him, and the king of Iubhar was willing that the wedding should go on; but the young king of Eirinn went home first, and he gathered together the high counsellors of the realm, and he told them what he desired to do; and the high counsellors of the realm of Eirinn counselled their king to marry the sister of the kin, of Iubhar. 1

The king; of Eirinn went back and he married the king's sister; and the king of the Iubhar and the king of Eirinn made "co-cheanghal" a league together. If straits, or hardships, or extremity, or anything counter should come upon either, the other was to go to his aid.

When they had settled each thing as it should be, the two kings gave each other a blessing and the king of Eirinn and his queen went home to Eirinn.

At the end of a little more than a year 2 after that they had a young son, and they gave him Eobhan as a

name. Good care was taken of him, as should be of a king's son. At the end of a little more than a year after that they had another son, and they gave him Claidhean as a name. Care was taken of this one as had been taken of his brother; and at more than a year after that they had another son, and they gave him Conall as a name, and care was taken of him as had been taken of the two others. 1

They were coming on well, and at the fitting time a teacher was got for them. When they had got about as much learning as the teacher could give them, they were one day out at play, and the king and the queen were going past them, and they were looking at their children (clann).

Said the queen, "This is well, and well enough, but more than this must be done for the children yet. I think that we ought to send them to Gruagach Bhein Eidinn to learn feats and heroes' activity (luth ghaisge), and that there is not in the sixteen realms another that is as good as the Gruagach of Beinn Eidinn. 1

The king agreed with her, and word was sent for the Gruagach. He came, and Eobhan and Claidhean were sent with him to Bein Eidinn to learn feats and activity, and what thing so ever besides the Gruagach could teach them.

They thought that Conall was too young to send him there at that time. When Eobhan and Claidhean were about a year by the Gruagach, he came with them to their father's house; they were sent back again, and the Gruagach was giving every learning to the king's children. He took them with him one day aloft up Beinn Eidinn, and when they were on high about half the mountain, the king's children saw a round brown stone, and as if it were set aside from other stones. They asked what was the reason of that stone being set aside so, rather than all the other stones on the mountain. The Gruagach said to them that the name of that stone was "Clach nan gaisgeach," the stone of the heroes. Any one that could lift that stone till he could place the wind between it and earth, that he was a hero.

Eobhan went to try to lift the stone; he put his arms about it, and he lifted it up to his knees; Claidhean seized the stone, and he put the wind between it and earth.

Said the Gruagach to them, "Ye are but young and tender yet, be not spoiling yourselves with things that are too weighty for you. Stop till the end of a year after this and you will be stronger for it than you are now."

The Gruagach took them home and taught them feats and activity, and at the end of a year he took them

again up the mountain. Eobhan and Claidhean went to the stone; Eobhan lifted it to his shoulder top, and set it down; Claidhean lifted the stone up to his lap, and the Gruagach said to them, "There is neither want of strength or learning with you; I will give you over to your father."

At the end of a few days after that, the Gruagach went home to the king's house, and he gave them to their father; and he said that the king's sons were the strongest and the best taught that there were in the sixteen realms. The king gave thanks and reward to the Gruagach, and he sent Conall with him.

The Gruagach began to teach Conall to do tricks and feats, and Conall pleased him well; and on a day he took Conall with him up the face of Beinn Eidinn, and they reached the place where the round brown stone was. Conall noticed it, and he asked as his brothers had done; and the Gruagach said as he said before. Conall put his hands about the stone, and he put the wind between it and earth; and they went home, and he was with the Gruagach getting more knowledge.

The next year after that they went up Beinn Eidinn where the round brown stone was. Conall thought that he would try if he was (na bu mhurraiche) stronger to lift the heroes' stone. He caught the stone, and he raised it on the top of the shoulder, and on the faggot gathering place of his back, and he carried it aloft to the top of Beinn Eidinn, and down to the bottom of Beinn Eidinn, and back again; and he left it where he found it.

And the Gruagach said to him, "Ach! thou hast enough of strength, if thou hast enough of swiftness."

The Gruagach shewed Conall. a black thorn bush that was a short way from them, and he said, "If thou canst

give me a blow with that black thorn bush yonder, before I reach the top of the mountain, I may cease giving thee instructions," and the Gruagach ran up the hill.

Conall sprang to the bush; he thought it would take too much time to cut it with his sword, and he pulled it out of the root, and he ran after the Gruagach with it and before he was but a short way up the mountain, Conall was at his back striking him about the backs of his knees with the black thorn bush.

The Gruagach said, "I will stop giving thee instructions, and I will go home and I will give thee up to thy father."

The Gruagach wished to go home with Conall, but Conall was not willing till he should get every knowledge that the Gruagach could give him; and he was with him after that more than a year, and after that they went home.

The king asked the Gruagach how Conall had taken up his learning. "It is so," said the Gruagach, "that Conall is the man that is the strongest and best taught in the sixteen realms, and if he gets days, he will increase that heroism yet."

The king gave full reward and thanks to the Gruagach for the care he had taken of his son. The Gruagach gave thanks to the king for the reward he had given him. They gave each other a blessing, and the Gruagach and the king's sons gave each other a blessing, and the Gruagach went home, and he was fully pleased. 1]

| Mac-Nair |

The young King of Eirinn and the king of Laidheann were comrades, and fond of each other; and they used to go to the green mound to the side of Beinn Euadain to seek pastime and pleasure of mind.

The King of Eirinn had three sons, and the King of Laidheann one daughter; and the youngest son that the King of Eirinn had was Conall. On a day, as they were on the green mound at the side of Beinn Eudain, they saw the seeming of a shower gathering in the heart of the north-western airt, and a rider of a black filly coming from about the shower; and he took (his way) to the green mound where were the King of Eirinn and the King of Laidheann, and he blessed the men, and he inquired of them. The King of Eirinn asked what he came about; and he said that he was going to make a request to the King of Eirinn, if it were so that he might get it. The King of Eirinn said that he should get it if it should be in his power to give it to him.

"Give me a loan of a day and a year of Conall thy son."

"I myself promised that to thee," said the King of Eirinn; "and unless I had promised thou shouldst not got him."

He took Conall with him. Now the King of Eirinn went home; he laid down music, and raised up woe, lamenting his son; he laid vows on himself that he would not stand on the green mound till a day and a

year should run out. There then he was at home, heavy and sad, till a day and a year had run.

At the end of a day and year he went to the green mound at the side of Beinn Eudain. There he was a while at the green mound, and he was not seeing a man coming, and he was not seeing a horseman coming, and he was under sorrow and under grief. In the same airt of the heaven, in the mouth of the evening he saw the same shower coming, and a man upon a black filly in it, and a man behind him. He went to the green mound where the man was coming, and he saw the King of Laidheann.

"How dost thou find thyself, King of Eirinn?"

"I myself am but middling."

"What is it that lays trouble on thee, King of Eirinn?"

"There is enough that puts trouble upon me. There came a man a year from yesterday that took from me my son; he promised to be with me this day, and I cannot see his likeness coming, himself or my son."

"Wouldst thou know thy son if thou shouldst see him?"

"I think I should know him for all the time he has been away."

"There is thy son for thee then," said the lad who came.

"Oh, it is not; he is unlike my son; so great a change as might come over my son, such a change as that could not come over him since he went away."

"He is all thou hast for thy son."

"Oh, you are my father, surely," said Conall.

"Thanks be to thee, king of the chiefs and the mighty! that Conall has come," said the King of Eirinn; "I am pleased that my son has come. Any

one thing that thou settest before me for bringing my son home, thou shalt get it, and my blessing."

"I will not take anything but thy blessing; and if I got thy blessing I am paid enough."

He got the blessing of the King of Eirinn, and they parted; and the King of Eirinn and his children went home.]

| MacNeill. |

After the sons of the King of Eirinn had gotten their learning, they themselves, and the king and the queen, were in the fortress; and they were full of rejoicing with music and joy, when there came a messenger to them from the King of Iubhar, telling that the Turcaich were at war with him to take the land from him; and that the realm of Iubhar was sore beset by the Turks; that they were (LIONAR NEARTHMHOR 'S BORB) numerous, powerful, and proud (RA GHARG), right fierce, merciless without kindliness, and that there were things incomprehensible about them; though they were slain to-day they would be alive to-morrow, and they would come forward to hold battle on the next day, as fierce and furious as they ever were; and the messenger was entreating the King of Eirinn to go to help the King of Iubhar, according to his words and his covenants. 1 The King of Eirinn must go to help the King of the Iubhar, because of the heavy vows: if strife, danger, straits, or any hardship should come against the one king, that the other king was to go to help him. 2]

| MacNair. |

They put on them forgoing; and when they had put on them for going away, they sent away a ship with provisions 1 and with arms. There went away right good ships loaded with each thing they might require; noble ships indeed. The King of Eirinn and the King of Laidheann gave out an order that every man in the kingdom should gather to go.

The King of Eirinn asked, "Is there any man about to stay to keep the wives and sons of Eirinn, till the King of Eirinn come back? Oh, thou, my eldest son, stay thou to keep the kingdom of Eirinn for thy father, and thine is the third part of it for his life, and at his death."

"Thou seemest light minded to me, my father," said the eldest son, "when thou speakest such idle talk; I would rather hold one day of battle and combat against the great Turk, than that I should have the kingdom of Eirinn altogether."

"There is no help for it," said the king. "But thou, middlemost son, stay thou to keep the kingdom of Eirinn for thy father, and thine is the half for his life, and at his death."

"Do not speak, my father, of such a silly thing! What strong love should you have yourself for going, that I might not have?"

"There is no help for it," said the King of Eirinn.

"Oh, Conall," said the king, "thou that hast ever earned my blessing, and that never deserved my curse, stay thou to keep the wives and sons of Eirinn for thy father until he himself returns home again, and thou

shalt have the realm of Eirinn altogether for thyself, for my life, and at my death."

"Well then, father, I will stay for thy blessing, and not for the realm of Eirinn, though the like of that might be." 1]

| MacNeill |

The king thought that Conall was too young for the realm to be trusted to him; he gathered his high counsellors and he took their counsel about it. The counsellors said that Conall was surely too young, but that was (FAILLINN A BHA DAONAN A DOL AM FEOBHAS) a failing that was always bettering; though he was young, that he would always be growing older; and that as Eobhan and Claidhean would not stay, that it was best to trust the realm to Conall].

| MacNair. |

Then here went the great nobles of Eirinn, and they put on them for going to sail to the realm of the Tuirc, themselves and the company of the King of Laidhean altogether. 2]

| MacNeill. |

They went away, and Conall went along with them to the shore; he and his father and his brothers gave a blessing to each other; and the King of Eirinn and his two sons, Eobhan and Claidhean, went on board of a ship, and they hoisted the speckled flapping sails up against the tall tough masts; and they sailed the ship fiulpande 3 fiullande. 4 Sailing about the sandy ocean, where the biggest beast eats the beast that is least, and the beast that is least is fleeing and hiding as best he

may; and the ship would split a hard oat seed in the midst of the sea, so well would she steer; and so she was as long as she was in the sight of Conall.

And Conall was heavy and dull when his father and brothers left him, and he sat down on the shore and he slept; and the wakening he got was the one wave sweeping him out, and the other wave washing him in against the shore.

Conall got up swiftly, and he said to himself, "Is this the first exploit I have done! It is no wonder my father should say I was too young to take care of the realm, since I cannot take care of myself."

He went home and he took better care of himself after that].

| MacNair |

There was not a man left in the realm of Eirinn but Conall; and there was not left a man 1 in the realm of Laidheann, but the daughter of the King of Laidheann, and five hundred soldiers to guard 2 her.

Anna Diucalas, daughter of the King of Laidheann, was the name of that woman, the very drop of woman's blood that was the most beautiful of all that ever stood on leather of cow or horse. Her father left her in his castle, with five hundred soldiers to keep her; and she had no man with her in Laidheann but the soldiers, and Conall was by himself in the realm of Eirinn.

Then sorrow struck Conall, and melancholy that he should stay in the realm of Eirinn by himself; that he himself was better than the people altogether, though they had gone away. He thought that there was nothing that would take his care and his sorrow from off him

better, than to go to the side of Beinn Eudainn to the green mound. He went, and he reached the green mound; be laid his face downwards on the hillock, and he thought that there was no one thing that would suit himself better, than that be should find his match of a woman. Then he gave a glance from him, and what should he see but a raven sitting on a heap of snow; 1 and he set it before him that he would not take a wife forever, but one whose head should be as black as the raven, and her face as fair as the snow, and her cheeks as red as blood. Such a woman was not to be found, but the one that the King of Laidheann left within in his castle, and it would not be easy to get to her, for all the soldiers that her father left to keep her; but be thought that he could reach her.

He went away, and there went no stop on his foot nor rest on his head, till he reached the castle in which was the daughter of the King of Laidheann.]

| MacNeil. |

He took (his burden) upon him, and he went on board of a skiff, and he rowed till he came on shore on the land of the King of Laidheann. 1 He did not know the road, but he took a tale from every traveller and walker that he fell in with, and when he came near to the dun of the king of Laidheann, he came to a small strait. There was a ferry boat on the strait, but the boat was on the further side of the narrows. He stood a little while looking at its breadth; at last he put his palm on the point of the spear, and the shaft in the sea, he gave his rounded spring, and he was over.]

| MacNair. |

| MacGilvray, Colonsay. |

ranks of soldiers. There were behind the warriors six heroes (GASGAICH) that were as mighty as the nine warriors and the nine ranks of soldiers. There were behind these six heroes three full heroes (LAN GASGAICH) that were as mighty as all that were outside of them; and there was one great man behind these three, that was as mighty as the whole of the people that there were altogether, and many a man tried to take out Ann Iuchdaris, 1 but no man of them went away alive.

He came to near about the soldiers, and he asked leave to go in, and that he would leave the woman as she was before.

"I perceive," said one of them, "that thou art a beggar that was in the land of Eirinn; what worth would the king of Laidheann have if he should come and find his daughter shamed by any one coward of Eirinn."

"I will not be long asking a way from you," said Conall.]

| MacNeil |

Conall looked at the men who were guarding the dun; he went a sweep round about with ears that were sharp to hear, and eyes rolling to see. A glance that he gave aloft to the dun he saw an open window, and Breast of Light on the inner side of the window combing her hair. Conall stood a little while gazing at her, but at last he put his palm on the point of hip, spear, he gave his rounded spring, and he was in at the window beside Breast of Light.

"Who is he this youth that sprang so roundly in at the window to see me?" said she.

"There is one that has come to take thee away," said Conall.

Breast of Light gave a laugh, and she said--"Sawest thou the soldiers that were guarding the dun?"

"I saw them," said he; "they let me in, and they will let me out."

She gave another laugh, and she said--"Many a one has tried to take me out from this, but none has done it yet, and they lost their luck at the end; my counsel to thee is that thou try it not."

Conall put his hand about her very waist; he raised her in his oxter; he took her out to the rank of soldiers; he put his palm on the point of his spear, and he leaped over their heads; he ran so swiftly that they could not see that it was Breast of Light that he had, and when he was out of sight of the dun he set her on the, ground.]

| MacNair. |

| MacNeill, Barra. |

Breast of Light heaved a heavy sigh from her breast. "What is the meaning of thy sigh?" said Conall.

"It is," said she, "that there came many a one to seek me, and that suffered death for my sake, and that it is (gealtair) the coward of the great world that took me away."

"I little thought that the very coward of Eirinn that should take me out, who staid at home from cowardice in the realm of Eirinn, and that my own father should leave five hundred warriors to watch me, without one drop of blood taken from one of them."]

| MacNeill. |

"How dost thou make that out?" said Conall.

"It is," said she, "that though there were many men about the dun, fear would not let thee tell the sorriest

of them who took away Breast of Light, nor to what side she was taken." 1

(That's it--the women ever had a torturing tongue, teanga ghointe.)]

| MacNeill. |

Said Conall--"Give me thy three royal words, and thy three baptismal vows, that thou wilt not move from that, and I will still go and tell it to them."

"I will do that," said she.]

| MacNair. |

Conall turned back to the dun, and nothing in the world, in the way of arms, did he fall in with but one horse's jaw which he found in the road;]

| MacNeill |

"It is this," said they, "to drive off his head and set it on a spike."

Conall looked under them, over them, through, and before them, for the one of the biggest knob and slenderest shanks, and he caught hold of the slenderest shanked and biggest knobbed man, and with the head of that one he drove the brains out of the rest, and the brains of that one with the other's heads. Then he drew his sword, and he began on the nine warriors, and he slew them, and he killed the six heroes that were at their back, and the three full heroes that were behind these, and then he had but the big man. Conall struck him a slap, and drove his eye out on his cheek, he levelled him and stripped his clothes off,]

| MacNair. |

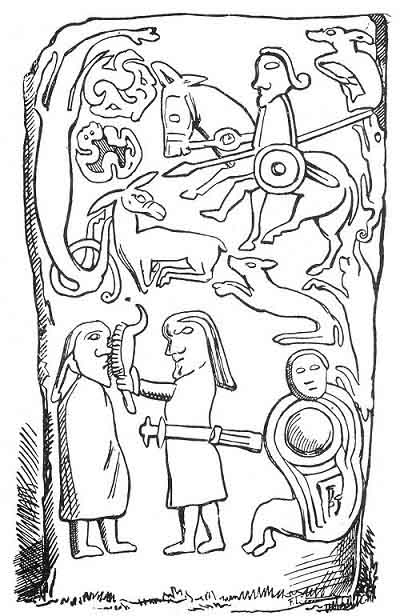

From a Stone in the Cemetery of Inch Brayoe, in the South Esk. Sculptured Stones of Scotland, Pl. lxviii.

those of his men that he would be; the plight that the youth who had come to the town had made of them. 1]

| MacNeill. |

Said Conall to him--"I lay it on thee as disgrace and contempt (tair agus tailceas) that thou must go stripped as thou art to tell to the king of Laidheann that Conall Guilbeanach came, the son of the king of Eirinn, and that he has taken away his daughter Breast of Light. 2

When the big man understood that he was to have his life along with him, he ran in great leaps, and in a rough trot, like a venomous snake, or a deadly dragon; 3 he would catch the swift March wind that was before him, but the swift March wind that was after him could not catch him. The King of Laidheann saw him coming, and he said, "What evil has befallen the dun

this day, when the big man is coming thus stark naked to us?" They sat down, and he came.

Said the king, "Tell us thy tale, big man?"

"That which I have is the tale of hate, that there came Conall Guilbeanach, son of the King of Eirinn, and slew all that there were of men to guard the dun, and it was not my own might or my own valour that rescued me rather than the sorriest that was there, but that he laid it on me as disgrace and reproach that I should go thus naked to tell it to my king, to tell him that there came Conall Guilbeanach, son of the King of Eirinn, and he has taken away Breast of Light, thy daughter."

"Much good may it do him then," said the King of Laidheann. "If it is a hero like that who has taken her away be will keep her better than I could keep her, and my anger will not go after her." 1]

| MacNair. |

Conall returned, and he reached the woman after he had finished the hosts.

"Come now," said he to Breast of Light, daughter of the King of Laidheann, "and walk with me; and unless thou hadst given me the spiteful talk that thou gavest, the company would be alive before thy father, and since thou gavest it thou shalt walk thyself. Let thy foot be even with mine."

(My fine fellow Conall, that's the way with her.)]

| MacNeill. |

She rose well-pleased, and she went away with him; they reached the narrows, they put out the ferry boat, and they crossed the strait. Conall had neither steed, horse, nor harness to take Breast of Light on, and she had to take to her feet.

When they reached where Conall had left the currach they put the boat on the brine, and they rowed over the ocean. They came to land at the lower side of Bein Eidin, in Eirinn. They came out of the boat, and they went on forward.]

| MacNair. |

They reached the green mound at the foot of Bein Eidin.]

| MacNeill. |

Conall told Breast of Light that he had a failing, every time that he did any deed of valour he must sleep before he could do brave deeds again. 1]

| MacNair. |

"There now, I will lay my head in thy lap."

"Thou shalt not, for fear thou should'st fall asleep."

"And if I do, wilt thou not waken me?"

"What manner of waking is thine?"

"Thou shalt cast me greatly hither and thither, and if that will not rouse me, thou shalt take the breadth of a penny piece of flesh and hide from the top of my head. If that will not wake me, thou shalt seize on yonder great slab of a stone, and thou shalt strike me

between the mouth and nose, and if that will not rouse me thou mayest let me be."

He laid his head in her lap, 1 and in a little instant be fell asleep.

He was not long asleep when she saw a great vessel sailing in the ocean. Each path was crooked, and each road was level for her, till she came to the green mound at the side of Bein Eidin.

There was in the ship but one great man, and he would make rudder in her stern, cable in her prow, tackle in her middle, each rope that was loose he would tie, and each rope that was fast he would loose],

| MacNeill. |

| MacNair. |

| MacNair and MacNeill. |

He came where Breast of Light was, and Conall asleep, with his head on her knee. He gazed at Breast of Light, and she said,--]

| MacNair. |

"What side is before thee for choice? Or where art thou going?

"Well, they were telling me that Breast of Light, daughter of the King of Laidheann, was the finest woman in the world, and I was going to seek her for myself."

"That is hard enough to get," said she. "She is in yonder castle, with five hundred soldiers for her guard, that her father left there."

"Well," said he, "though she were brighter than the sun, and more lovely than the moon, past thee I will not go."

"Well, thou seemest silly to me to think of taking me with thee instead of that woman, and that I am not worthy to go and untie her shoe."

"Be that as it will, thou shalt go with me.]

| MacNeill. |

"Thou hast the wishing knowledge of me," said she;

"I am not she, but a farmer's daughter, and this is my brother; he lost the flock this day, and he was running after them backwards and forwards throughout Bein Eudain, and now he is tired and taking a while of sleep."]

| MacNair. |

"Be that as it will," said he, "there is a mirror in my ship, and the mirror will not rise up for any woman in the world, but for "Uchd Soluisd," daughter of the King of Laidheann. If the mirror rises for thee, I will take thee with me, and if it does not I will leave thee there."

He went to the mirror, and fear would not let her cut off the little finger, and she could not awaken Conall. The man looked in the mirror, and the mirror rose up for her, and he went back where she was.]

| Macgilvray. |

Said the big one, "I will be surer than that of my matter before I go further." He plucked the blade of Conall. from the sheath, and it was full of blood.

[paragraph continues] "Ha!" said he, "I am right enough in my guess. Waken thy champion, and we will try with swift wrestling, might of hands, and hardness of blades, which of us has best right to have thee." 1

"Who art thou?" said Breast of Light.

"I," said the big man, "am Mac-a-Moir MacRigh Sorcha (son of the mighty, son of the King of Light). MacNair. It is in pursuit of thee I came." 2]

| MacNair |

"Wilt thou not waken my companion," said she.

He went, and he felt him from the points of the thumbs of his feet till he went out at the top of his head. "I cannot rouse the man myself; I like him as well asleep as awake."]

| MacNeill. |

Breast of Light got up, and she began to rock (a chriothnachadh) Conall hither and thither, but he would not take waking.

Said Mac-a-Moir--"Unless thou wakest him thou must go with me and leave him in his sleep."

Said she--"Give thou to me before I go with thee thy three royal words and thy three baptismal vows that thou wilt not seek me as wife or as sweetheart till the end of a day and a year after this, to give Conall time to come in my pursuit."

Mac-a-Moir gave his three royal words and his three baptismal vows to Breast of Light, that she should be a maiden till the end of a day and a year, to give time to Conall to come in pursuit of her, if he had so much courage. Breast of Light took the sword of Conall from the sheath, and she wrote on the sword how it had fallen out. She took the ring from off the finger of Conall, and she put her own ring on his finger in its stead, and put Conall's ring on her own finger, and she went away with Mac-a Moir, and they left Conall in his sleep.]

| MacNair. |

When Conall awoke on the green mound he had but himself, a shorn one and bare alone. Glance that he gave from him, what should he see but herds that the king of Eirinn and Laidheann had left, dancing for joy on the point of their spears. He thought that they were mocking him for what had befallen him. He went to kill the one with the other's head,]

| MacNeill. |

He said to one of them--"What fleeing is on the little herds of Bein Eidin before me this day, as if they were mad--are ye mocking me for what has befallen

me?" 1]

| MacNair. |

"We are not," said they; "it was grievous to us (to see) how it befell thee."

"What, my fine fellow, did you see happening to me?"]

| MacNeill. |

Said the little herd--"Thou art more like one who is mad than any one of us. If thou hadst seen the rinsing, and the sifting, and the riddling (an luasgadh, an cathadh, ’as an creanacadh) that they had at thee down at the foot of the hill, thou wouldst not have much esteem for thyself. I saw," said the little herd, "the one who was with thee putting a ring on thy finger."

Conall looked, and it was the ring of Breast of Light that was on his finger.

Said the little herd--"I saw her writing something on thy sword, and putting it into the sheath."

Conall drew his sword, and he read--"There came Mac-a-Moir, the king of Sorcha, and took me away, Breast of Light; I am to be free for a year and a day in his house waiting for thee, if thou hast so much courage as to come in pursuit of me."

Conall put his sword into its sheath, and he gave three royal words. 1]

| MacNair. |

| MacNeil. |

Said the little herd to him--"There came a ship to shore at the port down there. The shipmen (sgiobe) went to the hostelry, and if thou be able enough thou mayest be away with the ship before they come back." 1

Conall went away, and he went on board of the ship, and he was out of sight with her before the mariners missed him.]

| MacNair. |

| MacNeil. |

He leaped on shore, and he seized the prow of the ship, and he pulled her up on dry land, her own nine lengths and nine breadths, where the foeman's might could not take her out without feet following behind.

The lads of the realm of Lochlann, were playing shinny on a plain, and Gealbhan Greadhna, the son of the King of Lochlann, working amongst them. 3]

| MacNeil. |

did not know who they were, but he went to where they were, and it was the Prince of Lochlann and his two scholars, and ten over a score; and the Prince of Lochlann was alone, driving the goals against the whole of the two-and-thirty scholars.

Conall stood singing "iolla" to them, and the ball came to the side where he was; Conall struck a kick on the ball, and he drove it out on the goal boundary against the Prince of Lochlann. The Prince came where he was, and he said, "Thou, man, that came upon us from off the ocean, it were little enough that would make me take the head off thee, that we might have it as a ball to kick about the field, since thou wert so impudent as to kick the ball. Thou must bold a goal of shinny against me and against the two-and thirty scholars. If thou get the victory thou shalt be free; if we conquer thee, every one of us will hit thee a blow on the head with his shinny." 1]

| MacNair. |

"Well," said Conall, "I don't know who thou art, great man, but it seems to me that thy judgment is evil. If every one of you were to give me a knock on the head, you would leave my head a soft mass. I have no shinny that I can play with."

"Thou shalt have a shinny," said Gealbhan Greadhna.

Conall gave a look round about, and he saw a crooked stick of elder growing in the face of a bank. He gave a leap thither and plucked it out by the root,

and he sliced it with his sword and made a shinny of it. 1]

| MacNair. |

Then Conall had got a shinny, and he himself and Gealbhan Greadhna (cheery fire) went to play.

Two halves were made of the company, and the ball was let out in the midst. On a time of the times Conall got a chance at the ball; he struck it a stroke of his foot, and a blow of his palm and a blow of his shinny, and he drove it home.

"Thou wert impudent," said Gealbhan Greadhna, "to drive the game against me or against my share of the people."

"That is well said by thee, good lad! Thou shalt get two shares (earrann) of the band with thee, and I will take one share."

"And what wilt thou say if it goes against thee?"

"If it goes against me with fair play there is no help for it, but if it goes against me otherwise I may say what I choose,"

Then divisions were made of the company, and Gealbhan Greadhna had two divisions and Conall one. The ball was let out in the midst, and if it was let out Conall got a chance at it, and he struck it a stroke of his foot, and a blow of his palm, and a blow of his shinny, and he drove it in.

"Thou wert impudent," said Gealbhan Greadhna a second time, "to go to drive the game against me."

"Good lad, that is well from thee! but thou shalt get the whole company the third time, and what wilt thou say if it goes against thee."

"If it goes by fair play I cannot say a jot; if not, I may say my pleasure."

The ball was let go, and if so, Conall got a chance at it, and be all alone; and he struck it a stroke of his foot, and a blow of his palm, and a blow of his shinny, and he drove it in.

"Thou wert impudent," said Gealbhan Greadhna, "to go and drive it against me the third time."

"That is well from thee, good lad, but thou shalt not say that to me, nor to another man after me," and he struck him a blow of his shinny and knocked his brains out. 1]

| MacNeill. |

He looked (taireal) contemptuously at them; he threw his shinny from him, and he went from them.

He was going on, and he saw a little man coming laughing towards him.

"What is the meaning of thy laughing at me?" said Conall.

Said the little man, "It is that I am in a cheery mood at seeing a man of my country."

"Who art thou," said Conall, "that art a countryman of mine?"

"I," said the little man, "am Duanach MacDraodh (songster, son of magic), the son of a prophet from Eirinn. "Wilt thou then take me as a servant, lad?" 2

"I will not take thee," said Conall. "I have no way (of keeping) myself here without word of a gillie. What realm is this in which I am here?"

"Thou art," said Duanach, "in the realm of Lochlann."

Conall went on, and Duanach with him, and he saw a great town before him.

"What town is there, Duanach?" said Conall.

"That," said Duanach, "is the great town of the realm of Lochlann."

They went on and they saw a big house on a high place.

"What big house is yonder, Duanach?"

"That," said Duanach, "is the big house of the King of Lochlann;" and they went on.

They saw another house on a high place.

"What pointed house (biorach with points? pallisades or what) is there, Duanach?" said Conall.

"That is the house of the Tamhasg, the best warriors that are in the realm of Lochlann," said Duanach.

"I heard my grandfather speaking about the Tamhaisg, but I have never seen them; I will go to see them," said Conall.

"It were not my counsel to thee," said Duanach. 1]

| MacNair. |

On he went to the palace of the King of Lochlann (bhuail e beum sgeithe) and he clashed his shield, battle

or else combat to be sent to him, or else Breast of Light, the daughter of the King of Laidheann.

That was the thing he should get, battle and combat, and not Breast of Light, daughter of the King of Laidheann, for she was not there to give him; but he should get no fighting at that time of night, but he should get (fardoch) lodging in the house of the amhusg, where there were eighteen hundred amhusg and eighteen score; but he would get battle in the morrow's morning: when the first of the day should come.

’Twas no run for the lad, but a spring, and he would take no better than the place he was to get. He went, and he went in, and there was none of the amhuish within that did not grin. When he saw that they had made a grin, he himself made two.]

| MacNeill. |

"What was the meaning of your grinning at us?" said the amhusg.

What was the meaning of your grinning at me?" said Conall.

Said they, "Our grinning at thee meant that thy fresh royal blood will be ours to quench our thirst, and thy fresh royal flesh to polish our teeth."

And said Conall, "The meaning of my grinning is, that I will look out for the one with the biggest knob and slenderest shanks, and knock out the brains of the rest with that one, and his brains with the knobs of the rest.]

| MacNair. |

Every one of them arose, and he went to the door, and he put a stake of wood against the door. He rose up himself, and he put two against it so tightly that the others fell.

"What reason had he to do that?" said they.

"What reason had you to go and do it?" said he.

It were a sorry matter for me though I should put

two there, when you yourselves put one there each, every one that is within. 7)

"Well, we will tell thee," said they, "what reason we had for that: we have never seen coming here (one), a gulp of whose blood, or a morsel of whose flesh could reach us, but thou thyself, except one other man, and he fled from us; and now everyone is doubting the other, in case thou shouldst flee."

"That was the thing that made me do it myself likewise, since I have got yourselves so close as you are." Then he went and he began upon them. "I feared to be chasing you from hole to hole, and from hill to hill, and I did that." Then he gazed at them, from one to two, and he seized on the one of the slenderest shanks and the fattest head; he drove upon the rest, sliochd! slachd! till he had killed every one of them; and he had not a jot of the one with whom he was working at them, but what was in his hands of the shanks. 1

He killed every man of them, and though he was such a youth as he was, he was exhausted (enough-ified, if I might coin a word.) Then he began redding up the dwelling (reitach na h-araich) that was there, to clean it for himself that night. Then he put them out

in a heap altogether, and he let himself (drop) stretched out on one of the beds that was within. 1

There came a dream (Bruaduil) 2 to him then, and he said to him, "Rise, oh Conall, and the chase about to be upon thee."

He let that pass, and he gave it no heed, for he was exhausted.

He came the second journey, and he said to him, "Conall, wilt thou not arise, and that the chase is about to be upon thee."

He let that pass, and he gave it no heed; but the third time he came to him, he said, "Conall art thou about to give heed to me at all! and that thy life is about to be awanting to thee."

He arose and he looked out at the door, and he saw a hundred carts, and a hundred horses, and a hundred carters, coming with food to the amhusg; supposing that they had done for the youth that went amongst them the night before; and a piper playing music behind them, with joy and pleasure of mind.

They were coming past a single bridge, and the bridge was pretty large; and when Conall saw that they were together (cruin round) on the bridge, he reached the bridge, and he put each cart, and each horse, and each carter, over the bridge into the river; and he drowned the men.

There was one little bent crooked man here with them behind the rest.

"My heart is warming to thee with the thought that it is thou, Conall Gulban MacNiall Naonallaich, the name of a hero was on his hand a hundred years ere he was born."

"Thou hast but what thou hast of knowledge, and the share that thou hast not, thou wilt not have this day," said Conall Gulban.

He went away, and he reached the palace of the King of Lochlann; and he clashed his shield, battle or else combat to be given to him, or else Breast of Light, daughter of the King of Laidheann.

That was the thing which he should have, battle and combat; and not Breast of Light, for she was not there to give him. 1]

| MacNeill. |

(So he went back and he slept again.)

Word reached the young king of Lochlann, that the big man who came off the ocean had gone to the house of the "Tamhasg;" that they had set a combat, and that the "Tamhasgan" had been slain. The young king of Lochlann ordered four of the best warriors that were in his realm, that they should up to the house of the Tamhasg, and take off the head of the big man that that had come off the ocean, and to bring it up to him before he should sit down to his dinner.

The warriors went, and they found Duanach there, and they railed at him for going with the big man that came out of the outer land, 2 for they did not know who he was.

"And why," said Duanach, "should I not go with the man of my own country? but it you knew it, I am as tired of him as you are yourselves. He has given me much to do; see you I have just made a heap of corpses, a heap of clothes, and a heap of the arms of the "Tamhaisg;" and you have for it but to lift them along with you."

"It is not for that we came," said they, "but to slay him, and to take his head to the young king of Lochlann before he sits to dine. Who is he?" said they.

"He is," said Duanach, "one of the sons of the king of Eirinn."

"The young King of Lochlann has sent us to take his head off," said they.

"If you kill one of the children of the King of Eirinn in his sleep you will regret it enough afterwards," said Duanach.

"What regret will there be?" said they.

"There is this," said Duanach. "There will be no son to woman, there will be no calf to cow, no grass nor braird shall grow in the realm of Lochlann, till the end of seven years, 1 if ye kill one of the clan of the King of Eirinn in his sleep, and go and tell that to the young King of Lochlann."

They went back, and they told what Duanach had said.

The young King of Lochlann said that they should go back, and do as he had bidden them, and that they should not heed the lies of Duanach. The four warriors went again to the house of the Tamhasg," and they said to Duanach,--

"We have come again to take the head off the son of the King of Eirinn."

And Duanach said, "He is yonder then, over there, for you, in his sleep; but take good heed to yourselves, unless your swords are sharp enough to take off his head at the first blow, all that is in your bodies is to be pitied after that; he will not leave one of you alive, and he will bring (sgrios) ruin on the realm."

Each of them stretched his sword to Duanach, and Duanach said that their swords were not sharp enough, that they should go out to the Tamhasg stone to sharpen them. They went out, and they were sharpening their swords on the smooth grinding-stone of the Tamhasg, and Conall began to dream (again).

It seemed to him that he was going on a road that went through the midst of a gloomy wood, 1 and it seemed to him that he saw four lions before him, two, on the upper side of the rood, and two on the lower side, and they were gnashing their teeth, and switching their tails, 2 making ready to spring upon him, and it seemed to him that it was easier for the lions that were on the upper side of the road to leap down, than it was for the lions that were on the lower side to leap up; and it was better for him to slay those that were on the tipper side first, and he gave a cheery spring to be at them; and he sprang aloft through his sleep, and he struck his head against a tie beam (sail shuimear) that was across above him in the house of the "Tamhasgan," and he drove as much as the breadth of a half-crown piece of the skin off the top of his head, and then he was aroused, and he said to Duanach,--

"I myself was dreaming, Duanach," and he told him his dream.

And Duanach said, "Thy dream is a dainty to read. Go thou out to the stone of the Tamhasg, and thou wilt see the four best warriors that the King of Lochlann has, two on each side of the stone round about it, sharpening, their swords to take off thy head."

Conall went out with his blade in his hand, and he took off their heads, and he left two heads on each side of the stone of the Tamhasg and he came in where Duanach was, and he said, I am yet without food since I came to the realm of Lochlann, and I feel in myself that I am growing weak."

And Duanach said, "I wilt get thee food if thou wilt take my counsel, and that is, that thou shouldst go to court the sister of the King of Lochlann, and I myself will go to redd the way for thee. 1]

| MacNair. |

There were three great warriors in the king's palace in search of the daughter of the King, of Lochlann, and they sent word for the one who was the most valiant of them to go to combat the youth that had come to the town. This one came, and the Amhus Ormanach was his name, 2 and he and Conall were to try each other. They went and they began the battle, Conall and the Avas Ormanach. The daughter of the King of Lochlann

came to the door, and she shouted for Duanachd Acha Draohd. 1

"I am here," said Duanach.

"Well, then, if thou art, it is but little care thou hast for me. Many calving cattle and heifers gave my father to thy father, though thou art not going down, and standing behind the Avas Ormanach, and giving him the urging of a true wise bard 2 to hasten the head of the wretch to me for my dinner, for I have a great thirst for it."

"Faire! faire! watch, oh queen," said Duanach; "if thou hadst quicker asked it, thou hadst not got it slower."

Away went Duanach down, and it was not on the side of the Avas Ormanach he began, but on the side of Conall. "Thou hast not told it to me for certain, yet if it be thou, when thou art not hastening thine hand, and making heavy thy blow! And to let slip that wretch that ought to be in a land of holes, or in crannies of rock, or in otter's cairns! Though thou shouldst fall here for slowness or slackness, there would neither be wife nor sweetheart crying for thee, and that is not the like of what would befall him."

Conall thought that it was in good purpose the man was for him, and not in evil purpose; 3 he put his

sword under the sword of the Avas Ormanach, and he cast it to the skies, and then he himself gave a spring on his back, and he levelled him on the ground, and then he began to take his head off.

"Still be thy hand, O Conall," said Duanach Acha Draodh, "make him the binding of the three smalls there, until he gives thee his oaths under the edge of his set of arms, that there is no stroke he will strike for ever against thee." 1

"I have not got strings enough to bind him," said Conall.

"That is not my case," 2 said Duanach I have of cords what will bind back to back all that are in the realm of Lochlann altogether."

Duanach gave the cords to Conall, and Conall bound the Avas Ormanach. He gave his oaths to Conall under the edge of his set of arms, that he was a loved comrade to him for ever; and any one stroke he might strike that he would strike it with him, and that he would not strike a stroke for ever against him; and he left his life

with the Avus Ormanach.]

| MacNair. |

"Thou shalt have that woman for thyself," said Conall; "it is not her that I am courting and making love to."]

| MacGilvray. |

The daughter of the King of Lochlann was right well pleased that he had left his life with the Avus Ormanach, so that it might be her own but what should she do but send for Conall. 1

What should the daughter of the King of Lochlann do but send word for Conall to pass the evening together with the Queen and with herself, and if it were his will that she would not give him the trouble of taking a step with his foot, but that she would take him up in a creel to the top of the castle. Conall thought that much reproach should not belong to one that was in the realm

of Lochlann, against one that was in the realm of Eirinn, that he should go to do that. He went and he gave a spring from the small of his foot to the point of his palm, and from the point of his palm to the top of the castle, and he reached the woman where she was. 1

"If thou art now sore or hurt," said the daughter of the King of Lochlann, "there is a vessel of balsam (ballan fiochshlaint), wash thyself in it, and thou wilt be well after it."

He did not know that it was not bad stuff that was in the vessel. He put a little twig into the vessel, so that he might know what thing was in it. The twig came up full of sap (snodhach) as it went down. Then he thought that it was good stuff, and not bad stuff. He went and he washed himself in it, and he was as whole and healthy as he ever was. Then meat and drink went to them, that they might have pleasure of mind while passing the evening, and after that they went to rest; but he drew his cold sword between himself and the woman. He passed the night so, and in the morning he rose and went out of the castle. He clashed his shield without, and he shouted battle or else combat to be sent to him, or else Breast of Light, daughter of the King of Laidheann. It was battle and combat he should get, and not Breast of Light, for she was not there to give him.

Then the daughter of the King of Lochlann called out. "Art thou there, my brother?" 2

"I am," said her brother.

"Well," said she, "it is but little count that thou hadst of me. That man who has made me a woman of harrying and hurrying, to whom I fell as a wedded wife last night, not to bring me hither his head to my breakfast, when I am greatly thirsting for it."

"Faire! faire! watch, oh queen," said he, "if thou hadst asked it sooner thou hadst not got it slower. There are none of men, small or great, in Christendom, who will turn back my hand."

He went, and before he reached the door, he set earthquaking seven miles from him. At the first (mothar) growl he gave after he got out of the castle, there was no cow in calf, or mare in foal, or woman with child, but suffered for fear. He began himself and Conall at each other, and if there were not gasgich there at work it was a strange matter.]

| MacNeill. |

They drew the slender gray swords, and they'd kindle the tightening of grasp, from the rising of sun till the evening, when she would be wending west; and without knowing with which would be loss or winning. Duanach was singing iolladh to them, and when the sun was near about west. 1

Then the daughter of the King of Lochlann cried out for Duanach acha Draodh that he should go down to give the urging of a truewise bard to her brother, to bring her the head of the wretch to her breakfast, that she was thirsting greatly for it.

BARD.--From a cross near Dupplin. |

"Oh, Conall," said he, "thou hast not told me yet if it be thou. When thou art not hastening thine hand, but making heavy thy blow! and level that wretch that ought to be in a land of holes, or in clefts of rock, or in otters' cairns! Though thou shouldst fall, there would be no wife or sweetheart crying for thee, and not so with him." 1

Conall thought that it was in good purpose the man was for him, and that it was not in bad purpose. He put his sword under the sword of the King of Lochlann, and he cast it to the skies; and then he gave a spring himself on his back, and he levelled him on the ground, and he began to take off his head.

"Still thy hand, Conall," said Duanach achaidh

[paragraph continues] Draodh," little is his little shambling head worth to thee. 1]

| MacNeill. |

Said Conall to Duanach, "Reach hither to me my sword, that I may take off his head."

"Not I, indeed," said Duanach. "It is better for thee to have his head for thyself as it is, than five hundred heads that thou mightest take out with strife. Make him promise that he will be (diles duit) a friend to thee."

Conall made the young King of Lochlann promise with words and heavy vows, that he would be a friend to Conall Guilbeanach, the son of the King of Eirinn, in each strait or extremity that might come upon him, whether the matter should come with right or unright; and that Conall should have the realm of Lochlann under cess. 3

When the King of Lochlann had given these promises, Conall let him up, and they caught each other by the hand, and they made peace and they ceased.

And the young King of Lochlann gave a bidding to Conall that he should come in with him to his great house, to dine with him; and the young king set a double watch upon each place, so that none should come to disturb himself or the young son of the King of Eirinn, while they were at their feast.]

| MacNair. |

| MacGilvray. |

When each thing was ready the royal ones sat at the great board; they laid down lament, and they raised up music, with rejoicing and great joy]

| MacNair. |

| MacNeill. |

The soldiers were without watching, to guard the big house of the king, and they saw a great tasbarltach 1 coming the way; they had such fear before him that they thought they could see the great world between his legs. As he was coming nearer, the watch were fleeing till they reached the great house, and into the passage, and from the passage into the room where were the young King of Lochlann and the Young son of the King of Eirinn, at their feast; and the great raw bones that came began to fetter and bind the men, and to cast them behind him till he had bound every one of them; and till he reached the young King of Lochlann, and he and the big man wrestled with each other.]

| MacNair. |

| MacNeill. |

| MacNair. |

| MacGilvray. |

Conall gazed on all the company that was within, to try if he could see any man rising to stand by the king. When he saw no living man arising, he arose himself.]

| MacNair. |

| MacGilvary. |

"Has death ever gone so near thee as that?" said Conall.

"It has gone nearer than that," said the slender black man.

He let the weight more on him. "Has he gone as near as that to thee?"

"Oh, he has not gone; let thy knee be lightened, and I will tell thee the time that he went nearest to me."

"I will let thee; stand up so long as thou art telling it," said Conall. 1]

| MacNeill. |

Conall loosed the young King of Lochlann and his men from their bonds and from their fetters, and he sat himself and the young King of Lochlann at the board, and they took their feast; and the big man was cast in under the board. Again when they were at supper the king's sister was with them, and every word she said she was trying to make the friendship greater and greater between her brother and Conall. The big man was lying under the board, and Conall said to him, "Thou man that art beneath, wert thou ever before in strait or extremity as great as to be lying under the great board, under the drippings of the waxen torches of the King of Lochlann and mine?"

Said be, "If I were above, a comrade of meat and cup to thee, I would tell thee a tale on that."

At the end of a while after that, when the drink was taking Conall a little, he was willing to hear the tale of the man who was beneath the board, and he said to him, "Thou that art beneath the board, if I

had thy name it is that I would call thee; wert thou ever in strait or extremity like that?

And he answered as before.

Said Conall, "If thou wilt promise to be peaceable when thou gettest up, I will let thee come up; and if thou art not peaceable, the two hands that put thee down before, will put thee down again."

Conall loosed the man who was beneath, and he rose up aloft and he sat at the other side of the board, opposite to Conall; and Conall said,

"Aha! thou art on high now, thou man that wert beneath. If I had thy name it is that I would call thee. What strait or extremity wert thou ever in that was harder than to be laid under the board of the young king of Lochlann, and mine?"

203:1 This seems to shew that Celtic kings did not act without the consent of their chiefs; and this appears in other places, in this, and in many other stories. Iubhar is a name for Newry, but the story is not consistent with the supposition that Newry is meant. I suspect Jewry is the word, and that the Holy Land is meant.

203:2 The island reciter always say, "at the end of three quarters," etc.

204:1 The parentage and education of Conall are differently given in a very good, though short version, written by Mr. Fraser of Mauld. It is called the tale of Conall Guilbeanach, son of the King of Eirinn, and Gealmhaiseach mhin (fair, beauteous, smooth) daughter of the King of Lochlann.

A king of Eirinn was fond of the chase, and on a fine spring day he chased the deer till he lost his dogs and his people. In the gray of the evening he sat on the side of a green knoll, behind the wind and before the sun, and he heard a voice beside him say, "Hail to thee, King of Eirinn." "Hail to thyself, thou old gray man," said the king.

The old man took him into the mountain, and there he saw what he had never seen before: such food and drink, meat and music and dancing; and the old man had a beautiful daughter. He slept that night, and when he arose in the morning he heard the cry of a child; and he had to stay for the christening of his son, and he was named Conal Guilbeanach.

The king sent him venison from time to time, and be grew up to be a stalwart youth, swift and strong.

Then war sprung up between the King of Eirinn and the King of Lochlann; and the king sent Caoilte (one of the Feine), the swiftest man in the realm, for Conall, and he could not keep up with Conall on the way home.

The old gray man gave him a sword, and he said "Here is for thee, Conall, 'a Gheur Ghlas' (the keen gray), that I got myself from Oisean MacOscar na Feinne," etc.

An old man in Benbecula, Donald MacIntyre, told me this story in 1859. It lasted about an hour, and I did not take notes, but his version was the same as Mr. Fraser's, so far. A king of Eirinn gets lost in a magic mist, is entertained by a gray old p. 205 man, stays in his house for a night, sees the man's daughter, "and wheresoever the girl slept, it was there the king rose in the morning." He had been there a year and a day. Conall was born, and when the king went home he said nothing about his adventures.

The man who was sent for Conall, when war broke out with the Turks, and the king's two sons refused to stay, was so swift that he could cover seven ridges at a stride; but Conall beat him at all feats of agility, and when he came home with him he was seven ridges before him; and as he went he kept a golden apple playing aloft with the points of his two spears, etc.

Old Donald MacPhie, in South Uist, also told me the story. Like all versions which I have heard, it was full of metrical prose passages, "runs," as they are called. His version agreed with MacIntyre's as to the parentage of Conall.

The correct reading then seems to be, that Conall's two brothers were the sons of the queen, but that the hero was the son of the daughter of the Gruagach (? the Druid) of Beinn Eudain, an old gray man, who lived in the mountain, and who had been a comrade of Oisean and the Feine.

Conall had the blood of the ancient heroes in his veins, and they helped their descendant.

205:1 Dewar says, "a master of arts and sciences, a title, old Gaelic;" but he says so only on the authority of his stories. I suspect the word to be the same as Druidhach, a Druid or magician; p. 206 and that this relates to some real school of arms and warlike exercises. What the sixteen realms may mean I don't know.

208:1 So far I have followed MacNair's version, which is the only one with this part. I have shortened it by striking out repetitions; but I have followed Dewar's spelling of' the names. Thep. 209 next bit may be but another version of the education of the warrior, but it seems as if something were wanted to complete it. It is the beginning of the story as told in Barra, and I give it as part of the same thing. It agrees with the mysterious origin of Conall.

211:1 All versions agree that there was war between Eirinn and the Turks.

211:2 This is the fullest version. MacNeill gives the same incidents in a very few words. The Colonsay man, MacGilvray, begins here. "The King of Eirinn thought that he would go to put the Turks out of the realm of the Emperor--Impire." Another version also says that the king had gone to put the Turks out of the realm of the Emperor.

212:1 The word provēēshon has been adopted by reciters.

213:1 The Colonsay version and MacNair's give the same incidents; and Conall says that if the others get as much as Eirinn, they will be well off. "Thou art wise, Conall," said the king; and Conall was crowned King of Eirinn before the started.

213:2 The other versions do not say that the company of the King of Laidhean went, but it is implied.

213:3 Bounding.

213:4 Seaworthy.

214:1 A man, DUINE, means a human being.

214:2 GUARD, this is an English word which has crept into Gaelic stories, saighdair probably meant archer; it means soldier.

215:1 This incident, with variations, is common. It is clear that the raven ought to have been eating something to suggest the blood; and so it is elsewhere.

Mr. Fraser of Mauld, Inverness, East Coast.

He had gone to see his grandfather, the mysterious old gray man.

"When he got up in the morning there was a young snow, and the raven was upon a spray near him, and a bit of flesh in his beak. The piece of flesh fell, and Conall went to lift it; and the raven said to him, that Fair Beauteous Smooth was as white as the snow upon the spray, her cheek as red as the flesh that was in his hand, and her hair as black as the feather that was in his wing."

MacPhie, Uist.

On a snowy day Conall. saw a goat slaughtered, and a black raven came to drink the blood. "Oh," says he, "that I could marry the girl whose breast is as white as the snow, whose cheeks are red as the blood, and whose hair is as black as the raven; and Conall fell sick for love.

(Benbecula) Macintyre gave the same incident.

The Colonsay version introduces an old nurse instead.

MacNair simply says that Conall heard of the lady.

216:1 It seems hopeless to try to explain this topography. Laidheann should be Leinster, and Iubhar might be Newry, and Beinn Eudainn or Eideinn is like the Gaelic for Edinburgh, though the stories place the hill in Ireland; and here are the king of Eirinn and his son rowing and sailing about from realm to realm in Ireland, and the Turks at Newry a foreign land. If Iubhar mean Jewry, and this is a romance of the crusades, it is more reasonable.

217:1 This name is variously spelt:--1, as above; 2, Anna Diucalas; and 3, An Uchd Solais. The first is like a common French name, Eucharis, the second Maclean thinks has something to do with the raven black hair. The third was used by the Colonsay man and means bosom of light. All three have a similar sound, and I take Breast of Light as the most poetical.]

| MacNair |

219:1 Macgilvray also gives this incident, but omits the next. She kilted her gown and followed him.

220:1 What the artist meant who sculptured the stone from which this woodcut is taken is not clear, but the three lower figures p. 221 might mean Conall knocking out the big man's eye with a jaw bone, and the lady looking on. It might mean Samson slaying a Philistine. The upper part might represent the king hunting, but there is a nondescript figure which will not fit, unless it be the monster which was slain at the palace of the King of Light. The date and origin of stone and story are alike unknown, but they are both old and curious, and may serve as rude illustrations of past customs and dresses and of each other.

221:1 This is common to many stories. Beaarradh eòin us amadain, means shaving and clipping and stripping one side of a man, like a bird with one wing pinioned.

221:2 The spirit of this is like the Icelandic code of honour described in the Njal Saga. It was all fair to kill a man if it was done openly, or even unawares if the deed were not hidden, and here the lady was offended because the swain had not declared his name, and quite satisfied when he did.

221:3 Na leumanan garbh 's na, gharbh threte mar nathair nimh na mar bheithir bhéumanach.

222:1 The king's company had started for the wars; it is to be assumed the king followed.

223:1 MacNair also gives the next passage in different words, and with the variation that the joint of his little finger was to be cut off.

Macgilvray, the same in different words. According to the introduction to Njal Saga, there were in Iceland long ago gifted men of prodigious strength, who, after performing feats of superhuman, force, were weak and powerless for a time. While engaged in London about this story, an Irish bricklayer came to mend a fire-place, and I asked him if he had ever heard of Conall Gulban, "Yes sure," said the man with a grin, "he was one of the Finevanians, and when he slept they had to cut bits off him, before he could be wakened. They were cutting his fingers off." And then he went away with his hod.

The incident is common in Gaelic stories, and Conall is mentioned in a list of Irish stories in the transactions of the Ossianic society.

224:1 And he laid his head in her lap, and she--dressed--his hair. (MacPhie, Uist.) This is always the case in popular tales of all countries, and the practice is common from Naples to Lapland. I have seen it often. The top of his little linger was to be cut off to rouse him, and if that failed, a bit from his crown, and he was to be knocked about the ribs, and a stone placed on his chest.

224:2 MacGilvray gives the incident in different words.

224:3 Long means a large ship.

226:1 A good illustration of the law of the strongest, which seems to have been the law of the Court of Appeal in old times in Iceland, and probably in Ireland and Scotland also.

226:2 Here, as it seems to me, the mythological character of the legend appears. Sorcha is light, in opposition to Dorch, dark; and further on a lady is found to match the king of Sorcha, who is in a lofty turret which no man could scale, but which the great warrior pulled down. So far as I know there is no place which now goes by the name of Sorcha, unless it be the island of Sark. According to Donald MacPhie (Uist), this was Righ-an-Domhain, the King of the Universe, which again indicates mythology.

227:1 Macgilvray awakens him by a troop of school-boys who were playing tricks to him.

228:1 He also gives the following passage, but less fully.

228:2 It was a common practice, according to the Njal Saga, for the old Icelands to bind themselves by vows to perform certain p. 229 deeds, and, according to Irish writers, a like practice prevailed in Ireland. it seems that the custom is remembered and preserved in these stories. The fruit, TORADH, rather means a harvest; he will leave a harvest of dead reaped by his hand.

229:1 Mr. Fraser, Invernesshire. "His grandfather took him to the side of the sea, and he struck a rod that was in his band on a rock, and there rose up a long ship under sail. The old man put "a gheur ghlas," the keen gray (sword) on board, and at parting he said, in every strait in which thou art for ever remember me."--MacPhie. He wished for his grandfather, who came and said, "Bad! bad! thou hast wished too soon," and raised a ship with his magic rod.

229:2 The only variation here is the words.

229:3 I have never seen the game of shinny played in Norway, but there is mention of a game at "ball" in Icelandic sagas.

230:1 Iomhair Oaidh MacRigh na Hiribhi, Iver, son of the King of Bergen, is the person who plays this part in the Inverness-shire version. He was a suitor, and he was thrashed, but he afterwards plays the part of the King of Sorcha, and is killed. MacPhie makes him a young man, and a suitor for the Princess of Norway.

231:1 According to MacPhie (Uist), he wished for his grandfather, who appeared with an iron shinny, and said, "Bad, bad, thou hast wished too soon."

232:1 This description of a game of shinny is characteristic, and the petulance of Prince Cheery Fire, with his two-and-thirty toadies, and the independence of the warrior who came over the sea, and who would stand no nonsense, are well described, MacNair's version is not so full, nor is the catastrophe so tragic, but otherwise the incidents are the same.

232:2 From the Njal Saga it appears that the Northmen, in their raids, carried off the people of IRELAND, and made slaves of them. Macgilvray called this character Dubhan MacDraoth, blacky, or p. 233 perhaps crook, the son of magic, and he explained, that draoth was one who brought messages from one enemy to another, and whose person was sacred.

233:1 Here my two chief authorities vary a little in the order of the incidents. MacNair sends him first to his house, the other takes him there later; they vary but little in the incidents. Macgilvray takes him at once to the palace, where he finds a great chain which he shakes to bring out the foe.

235:1 AMHAS, a madman, a wild ungovernable man; also, a dull stupid person (Armstrong). AMHASAN, a sentry (ditto); also, a wild beast, according to the Highland Society Dictionary. Perhaps these may have something to do with the Basemarks of the old Norsemen, who were "public pests," great warriors, half crazy, enormously strong, subject to fits of ungovernable fury, occasionally employed by saner men, and put to death when done with. The characters appear in many Highland tales; and an Irish blind fiddler told me a long story in which they figured. I suspect this guardhouse of savage warriors has a foundation in fact. Macgilvray gives the incidents also.

236:1 He made himself a bed of rushes at the side of the house.--Macgilvray.

236:2 This word, thus written, is in no dictionary that I have, but it is the same as brudair; and, the other version proves that a dream is meant. It is singular to find a dream thus personified in the mouth of a Barra peasant.

237:1 MacNair has not got this adventure of the carts; and MacNeil has not the next adventure, unless it be the same considerably varied. I give both upon chance.

237:2 "AN FHOIRS TIR;" this word is now commonly applied to the furthest ground known, such as the outermost reef or even fishing bank; it is also written oirihir, edge-land.

238:1 Cha bhith mac aig bean; cha bhith laogh aig mart; 's cha chinn fear na fochan, ann an righachd Lochlann, gu ceann seachd bliadhna, etc.

239:1 Coille udlaidh, lonely, morose, churlish, gloomy. Pr. ood-lai. Compare outlaw, outlying.

239:2 A casadh am fiacall 's a sguitse le n' earball.

240:1 He has not got the next adventure, which I take from MacNeill.

240:2 AMHUS, the savage, or wild man, ORMANACH is not so clear; written from ear it might be a word beginning with an aspirated silent letter, such as th, which would make the word "noisy," or it may be some compound of OR gold, such as OR-MHEINNEACH, gold-ore-ish, which would make him the wild man of the gold mines, or armour, or hair, or something else. Macgilvray called him an Amhas Orannoch, the wild man of songs.

241:1 Songstership of Magic field, which is MacNeill's name for the character.

241:2 Brosnachadh file fiorghlic. It is said that the bards from the earliest of times sang songs of encouragement to the warriors. The old Icelanders, as it is asserted in their sagas, sung themselves in the heat of the fight, and here is a tradition of something of the kind. In Stewart's collection, 1804, is the battle song of the Macdonalds for the battle of Harlaw.

241:3 Deagh run, droch run. Rùn has many meanings--love, etc.; purpose, etc.; a person beloved; a secret, a mystery; and, p. 242 according to Armstrong, it is the origin of "runic." The man who told this story clearly meant "purpose" by run; but perhaps the original meaning of the passage which comes repeatedly in this story was that Songstership of Magic field sang "good runes for the victory of his countrymen." It must be remembered that Barra was in the way of Norsemen, and that their ways of life throw light on Gaelic traditions. According to Macgilvray--another islander--Dubhan MacDraoth was the Draoth (? herald) of the king of Eirinn when he went to put the Turk out of the realm of the emperor, and the king of Lochlann brought him home thence, and he was his draoth. As there was a guard of Norsemen in Constantinople this looks like a possible fact.

242:1 "The d---l has sworn by the edge of his knife."--Carle of Kellyburn Braes, Old Song.

242:2 Cha 'n e sin domh 's e.--It is not that to me it is.

243:1 MacNair gives the following incidents more in detail, and more as matter of fact. The bard, to get food for the warrior, persuades the lady that he has come to court her, and with her consent, takes him food, and guides him to her chamber. He places a drawn sword between them, and never speaks. The bard sleeps on the stair outside; the king's men seek in vain for Conall; and in the morning the bard explains the mystery of the drawn sword to the lady, who is content. And so it happens thrice, when Conall feels able to fight the lady's brother, and the lady finds that the warrior is faithful to his first love, and the bard a cunning deceiver. This incident is very widely known in popular tales. See the "Arabian Nights," Grimm, etc. "Gu de am fath ma 'n do rinn se è mata?" orsa ise. "Tha," orsa Duanach, "tha e a los ma bhitheas leanabh gille eadar sibh gu am bi e na fhear claidheamh cho math ris fein." Thuirt ise, "Ach na an saoillinn sin dheanainn a bheatha ciod air bhith doigh air an tigeadh e."

244:1 Thug e leum o chaol a choise go barr a bhoise, 's o barr a bhoise go mullach a chaisteil.

244:2 According to MacNeill it was her father; and as the young king goes away afterwards and is married, I follow MacNair. MacNeill killed a brother at landing. MacNair left him alive to p. 245 be introduced further on, so I have altered one word in MacNeill's account of the fight, and assume that Prince Cheery fire was a younger brother of the young king.

245:1 Tharruing iad an claidheamhainn caola glasadh a's dh' fhadadh iad teaneacha dorn, o'n a dh' eireadh a ghrian gus am feasgar tra bhithidh i a dol siar.

246:1 As this is a kind of chorus, and probably old, I give the original. Nur nach 'eil thu luaireachadh do laimh, ach a tromachadh do bhuille, agus a bhiast sin a bo choir a bhi 'n talamh toll, na'n sgeilpidh chreag na 'n carn bhiasta dugha leagail! gad a thuiteadh tusa, cha bhiodh bean na leannan a ghlaoidheadh air do shon, cha b' ionann sin a's esan.

247:1 MacNeill, who goes on to repeat the binding of this warrior in the same words. For variety, I substitute MacNair's description of the same fight, which he, like the other, repeats several times as a kind of chorus.

247:2 Chuir iad na duirn bhogadh ghealladh an cneasadh a cheile, ach cha bu fhada a gabh iad do an ghleachd gus an tug Conall cneadhaiseach a chridhe do righ og Lochlann air clachan cruaidh a chausair. As written by Dewar.

247:3 Fo chis, tribute or subjection. It seems almost a hopeless task to make romance reasonable, and yet I am convinced that these are semi-historical romances, When it is certain that Norse sea-rovers, were actually settled in the Hebrides, and wandered from America to Constantinople, and levied tribute wherever they could; when it appears from their sagas, which p. 248 are believed to be almost true history, that these raids were often made in single ships, and when simple Icelanders fought with Orkney earls and Norse kings, and Norman adventurers conquered England; it seems possible that one of the body guard from Constantinople might become "Emperor of the world" in the Hebrides, and a voyager from Greenland "king of the green isle that was about the heaps of the deep;" and that such exploits as these men performed might be magnified, and applied to a Celtic warrior by Celtic bards; or that a Celtic warrior may have done as much. It is admitted that Irish priests had found their way to Iceland before the Norsemen went there, and if so, perhaps Irish warriors may have been pirates or varangians, and successful in forays on the Vikings, as Vikings were in Irish forays. We believe the Sagas, so far as they are reasonable; why should not truth be sifted from these romances also.

249:1 Large, lean boned, savage and swarthy.--Dewar.

249:2 MacNeill, who says he was a slender black man.

250:1 MacNair's version is almost the same in different words. This has some resemblance to the story of Conall, Nos. V. VI. VII.; but the adventures of this man are quite different. Macgilvray gives the same story.