Sacred Texts Legends & Sagas Celtic Index Previous Next

THE districts comprehended at an early period under the name of Cumbria were of considerable extent; and, as its name indicates, occupied by a Cymric population.

Joceline, who wrote about the year 1180, in his life of Kentigern, states that the limits of his bishopric were coextensive with those of the "regio Cambrensis," and extended from the Roman wall to the "flumen Fordense;" but it originally extended even further south than this, for Joceline was judging by the extent of the diocese of Glasgow, and Carlisle and the district surrounding it had, after the Norman Conquest of England, been formed into an earldom, and in 1132 erected into the diocese of Carlisle. In a document printed in the Iolo MSS., the extent of many of the old Welsh districts is given, and the district of Teyrnllwg is said to have extended from Aerven to Argoed Derwennydd--that is, to the Forest upon the Derwent. This river, which falls into the Western Sea at Workington, now divides the diocese of Chester from that of Carlisle; and as soon as we pass the Derwent, dedications of churches to Kentigern commence. The district south of the Derwent had very early come under the power of the kings of Northumberland,

and the independent states of the Cymry probably extended from the Derwent and from Stanmore to the Clyde, including Westmoreland (with the exception of Kendal), and the central districts in Scotland, of Teviotdale, Selkirk, and Tweeddale. It comprehended what afterwards formed the dioceses of Glasgow and Carlisle; and its Cymric population appears as a distinct people, even as late as the battle of the Standard, in 1130, where they formed one of the battalions in King David's army, consisting of the Cumbrenses and Tevidalenses.

They appear to have been composed of numerous small states under their petty kings.

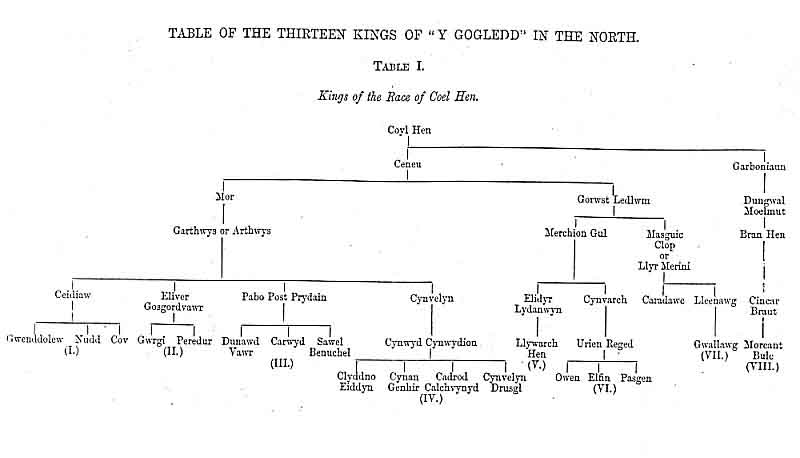

There is a document in one of the Hengwrt MSS., transcribed about 1300, with the title of Bonhed Gwyr y Gogledd, or Genealogies of the Men of the North--a name used to designate these Northern Cymry. It gives the pedigrees of twelve families, and they fall into three groups--one consisting of six families, whose descent is traced from Ceneu, son of Coel; the second, of five families descended from Dyfawal Hen, or the aged, grandson of Macsen Guledig, the Roman Emperor; and the third, of one family connected with the north, apparently through the female line. The first group again falls into two branches respectively derived from two sons of Ceneu, son. of Coel, Gorwst Ledlwm, and Mar or Mor. To Merchion Gul, the son of Gorwst Ledlwm, are given two sons--Cynvarch, the father of Urien and Elidir Lydanwyn, father of Llywarch Hen. To Garthwys

or Arthwys, son of Mor, are given four sons--Ceidiaw, the father of Gwenddolew, Nudd, and Cov; Elivir Gosgorddvawr, or of the large retinue, the father of Gwrgi and Perodur; Pabo Post Prydain, or the pillar of Britain, the father of Sawyl Benuchel; Dunawd Vawr, and Carwyd; and Cynvelyn, the grandfather, by his son Cynwyd Cynwydion, of Clyddno Eiddyn, Cynan Genhir, Cadrod Calchvynydd, and Cynvelyn Drwsgl.

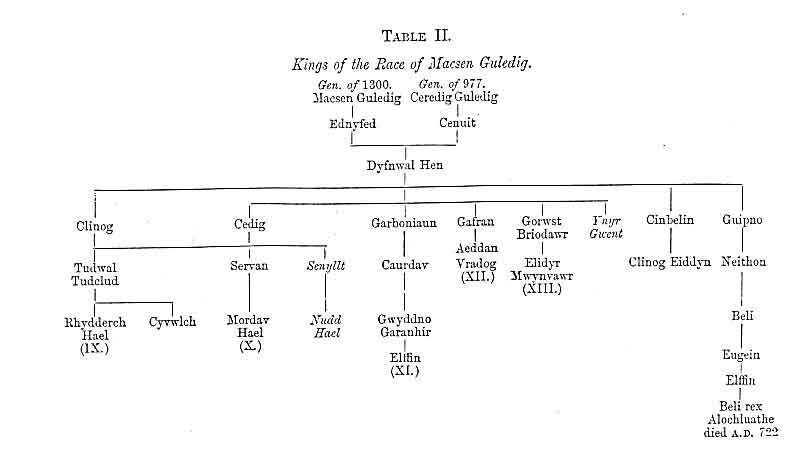

The second group, consisting of the descendants of Dyfnwal Hen, also falls into four branches, descended of four sons of Dyfnwal Hen:--Cedig, father of Tudwal Tudclud, the father of Rydderch Hael, Senyllt, father of Nudd Hael, and Servan, father of Mordav; Garwynwyn, father of Caurdav, father of Gwyddno Garanhir; Aeddan Vradog; and Gorwst Briodawr, father of Elidr Mwynvawr.

The genealogies annexed to Nennius in 977 do not greatly differ from this. In the first group of families descended from Coel they add the pedigrees of two additional families--that of Gwallawg ap Leenawg and of Morcant. In the second group, the most important variation is that the descent pf Dyfnwal Hen, the common ancestor is not brought from Macsen Guledig, but from a Caredig Guledic, whose pedigree is taken back to a Confer the Rich; and that the descent of the later kings of Strathclyde from Dyfnwal Hen is given.

Adding, therefore, the two additional families descended from Coel, we have eight in the first group, and five in the second--in all, thirteen; and the following tables will show their connection:--

Table I. The Thirteen Kings of Y Gogledd in the North

Table II. Kings of the Race of Macsen Guledig.

It is, of course, not maintained that those genealogies are, strictly speaking, historical, and that each link in the pedigree represents a real person; but they are valuable as conveying a general idea of the period, and tribal connection of these "Gwyr y Gogledd," or Men of the North. The thirteen families no doubt represented as many petty states in Cumbria; and in the two groups we can see the mixture of two races--the provincial Roman and the native Cymric--and the small septs into which they were respectively divided.

There are indications, derived from their names, their history, and from local tradition, which connect most of these families with localities within the limits of Cumbria. Beginning with the first group, Ayrshire--divided into the three districts of Cuningham, Kyle, and Carrick--seems to have been the main seat of the families of the race of Coel, from whom indeed the district of Coel, now Kyle, is said traditionally to have taken its name. There is every reason to believe that Boece, in filling up the reigns of his phantom kings with imaginary events, used local traditions where he could find them; and he tells us "Kyl dein proxima est vel Coil potius nominata, a Coilo Britannorum rege ibi in pugna cæso;" and a circular mound at Coilsfield, in the parish of Tarbolton, on the highest point of which tire two large stones, and in which sepulchral remains have been found, is pointed out by local tradition as his tomb. He likewise connects two of his early kings with this part of the country. These are Caractacus and

[paragraph continues] Corbredus Galdus, son of his brother Corbredus. He identifies the first with the British king Caractacus, and the second with Galgacus, who fought against Agricola; but he says of them--"Horum quæ de Carataco, Corbredo ac Galdo Scotorum regibus, his voluminibus memoriæ dedimus, nonulla ex nostris annalibus, at longe uberiora ex Cornelio Tacito sunt deprompta." While adapting the events from Tacitus, he likewise made use of native traditions. His Caratacus is obviously the name Caradawg; and his Galdus I believe to be taken from Gwallawg ap Lleenawg. It is curious that these two warriors of the "Gwyr y Gogledd" should have the same relationship of uncle and nephew. Now he says that in Carrick, one of the three divisions of Ayrshire, and lying to the south of Kyle, "erat civitas tum maxima a qua Caractani regio videtur nomen sortita. In ea Caratacus natus, nutritus, educatus." Of Galdus or Gwallawg he says that, on his death, "Elatum est corpus . . . in vicino campi ut vivens mandaverat, est conditum ubi ornatissimum ei monumentum patrio more, immensis ex lapidibus est erectum." Symson, in his Description of Galloway, written in 1684, says--"In the highway between Wigton and Portpatrick, about three miles westward of Wigton, is a plaine called the Moor of the Standing Stones of Torhouse, in which there is a monument of three large whinstones, called King Galdus's tomb surrounded, at about twelve feet distance, with nineteen considerable great stones, but none of them so great as the three first mentioned, erected in a circumference."

[paragraph continues] And a similar monument is described in a MS. quoted by Dr. Jamieson, in his edition of Bellenden's Boece, as existing in Carrick:--"There is 3 werey grate heapes of stonnes, callit wulgarley the Kernes of Blackinney, being the name of the village and ground. At the suthermost of thir 3 cairnes are ther 13 great tall stonnes, standing upright in a perfyte circkle, aboute some 3 ells ane distaunt from ane other, with a gret heighe stonne in the midle, which is werily esteemid be the most learned inhabitants to be the buriall place of King Caractacus." The names of Caradawg and of Gwallawg seem, therefore, connected with the district of Carrick and that of Wigton, extending between Carrick and the Solway Firth.

Gwenddolew, the son of Ceidiaw, is clearly connected with Ardderyd, now Arthuret, where his name still remains in Carwhinclow; and between this and the southern boundary of Cumbria, at the Derwent, others of the descendants of Coel may have had their seat. We have Urien connected with the district at the northern wall,. termed Mureif or Reged, in which Loch Lomond was situated. And of the, family of Cynwyd Cynwydion one son, Clyddno Eiddyn, is connected by his name with Eiddyn, or Caer Eiddyn, now Caredin, termed in the Capitula of Gildas "civitas antiquissima;" and another, Catrawd Calchvynyd, with Kelso. Calchvynyd is simply Calch Mountain, or chalk mountain; and Chalmers, in his Caledonia (vol. ii. p. 156), says: "It (Kelso) seems to have derived its ancient

name of Calchow from a calcareous eminence which appears conspicuous in the middle of the town, and which is still called the Chalk Heugh."

The other group of families descended from Dyfnwal Hen are not so easily placed, as they soon acquired the supremacy over the whole region, but it is probable that they were more immediately connected with the central districts, Annandale, Clydesdale, Teviotdale, Yarrow, Selkirk, and Tweeddale. After Kentigern was recalled to Cumbria, it is stated by Joceline that he placed his episcopal seat for some time at Hoddelm or Hoddom in Annandale, where Rydderch's power may have been greatest, and his father's name of Tutgual Tutclud seems to connect him with the "flumen Clud," probably the upper part, as we read in the acts of St. Kentigern of a "regina de Caidzow" or Cadyow, the old name of the middle district of the vale of the Clyde, which indicates a separate small state. Between Strathclyde and Ayrshire lay the district of Strathgryf, now the county of Renfrew, and this part of Cumbria seems to have been the seat of the family of Caw, commonly called Caw Cawlwydd or Caw Prydyn, one of whose sons was Gildas. In one of the lives of Gildas he is said to be son of Caunus who reigned in Arecluta. In the old description of Scotland we are told that Aregaithel means Margo Hibernensium. The name Arecluta is similarly composed, and signifies a district lying along the Clyde, and Strathgrife or Renfrewshire lies in its whole extent along the south bank of the Clyde. In the life of St. Cadocus a singular

legend is preserved. He is said to have visited Scotland, and while he was building a monastery there near the mountain Bannawc he found the grave of a giant, who rose and informed him that he was Caw of Prydyn, and that he had been a king who reigned beyond the mountain Bannawc, and in another legend we are told that this monastery was in regione Lintheamus (Lives of Cambro British Saints). Now the parish of Cambuslang, on the Clyde, is dedicated to St. Cadoc, and through the adjoining parish of Carmunnock, formerly Carmannock, runs a range of hills, now called the Cathkin hills, which separates Strathclyde from Ayrshire and terminates in Renfrewshire. This must be the mountain Bannawc, and the name is preserved in Carmannock, B passing into M in Welsh in combination, and Caw is thus represented in this legend also as reigning in Strathgryf or Renfrewshire. The name Lintheamus is probably meant for Lintheamus or Cambuslang.

There is a curious legend preserved in the Venedotian code of the old Welsh laws, which is as follows:

"Here Elidyr Muhenvaur, a man from the north was slain and, after his death, the "Gwyr y Gogled," or Men of the North, came here to avenge him. The chiefs, their leaders, were Clyddno Eiddin; Nudd Hael, son of Senyllt; and Mordaf Hael, son of Seruari, and Rydderch Hael, son of Tudwal Tudglyd; and they came to Arvon, and because Elidyr was slain at Aber Mewydus in Arvon, they burned Arvon as a further revenge. And then Run, son of Maelgwn, and the men of Gwynedd, assembled in arms, and proceeded to the banks of the Gweryd "yn y Gogledd," or in the north, and there they were long disputing who should take the lead through the river Gweryd. Then Run despatched

a messenger to Gwynedd to ascertain who was entitled to the lead: some say that Maeldaf the elder, the Lord of Penardd, adjudged it to the men of Arvon; Joruerth, the son of Madog, on the authority of his own information, affirms that Idno the aged assigned it to the men of the black-headed shafts. And thereupon the men of Arvon advanced in the van, and were valorous there. And Taliessin sang--

"Behold! from the ardeney of their blades,

With Run, the reddener of armies,

The men of Arvon with their ruddy lances."

Old Welsh Laws, p. 50.

Elidyr Mwynvawr was the head of one of the families descended from Dyfnwal Hen, and so were. Rydderch Hael, Nudd Hael, and Mordav Hael, and Clyddno Eiddyn was of the race of Coel. They are called "Gwyr y Gogledd," or Men of the North, and the scene of the dispute as to who should lead was the banks of the river Forth, for the river Gweryd in the north is the Forth, it having been, according to the old description of 1165, called, "Britannice, Weryd."

The author of the Genealogia annexed to Nennius describes four of these kings of the north--Urien, Rydderch, Gwallawg, and Morcant--as warring against Hussa, son of Ida, the king of Bernicia, who reigned from 567 to 574; and the battle of Ardderyd, fought in 573, by which the anti-Christian party were finally crushed, resulted in the consolidation of these petty states into the kingdom of Cumbria or Strathclyde, and the establishment of Rydderch as king in the strong fortress of Alclyde or Dumbarton rock, which became from henceforth the chief seat of the kingdom. Here we find Rydderch established when he sent a

message to St. Columba, to consult him, as supposed to possess prophetic power, whether he should be slain by his enemies, as recorded by Adomnan in his Life of St. Columba, who calls him "Rex Rodarcus filius Totail qui Petra Cloithe regnavit." St. Columba's reply--"De eodem rege et regno et populo ejus"--was, that he would not fall into the hands of his enemies, but die in his own house: which prophecy, adds Adomnan, as fulfilled, as he died a peaceful death.

If Joceline reports a real fact, when he says that he died in the same year as St. Kentigern, his death must have taken place either in the year 603 or 614, according to which is the true date of St. Kentigern's death; 1 and during that time he consolidated his power, and re-established the bishopric of Glasgow.

The chronicle of 977 records, in 580, the death of Gwrgi and Peredur, the sons of Eliver Gosgorddvaur, another of these northern kings, and, in 593, the death of Dunawd, son of Pabo Post Prydain; and the Genealogia state that against Theodric, son of Ida, who reigned in Bernicia from 580 to 587, Urien with his sons fought valiantly, and adds, "In illo tempore aliquando hostes, nunc cives, vincebantur," showing the character of the struggle which was taking place between the Cymric population and the increasing power of the Angles.

In 603 a great effort appears to have been made by the Celtic tribes to drive back the Angles, under Aidan, king of the Scots who inhabit Britain, whom Bode describes as invading Bernicia with an immense and brave army, and being defeated and put to flight at Degsastan, now Dawston, in Liddesdale, where almost all his army were slain, and he himself escaped with a few only of his followers. This disaster must have crushed the efforts of the Celtic tribes to resist the Angles for the time, and enabled the latter to extend their territories unresisted, till in the reign of Edwin they reached the shores of the Firth of Forth.

After the death of Edwin, when Cadwallawn had established his power, Tighernac records, in 638, the battle of Glenmairison, in which the people of Donaldbrec were put to flight, "et obsessio Etain," and afterwards, in 642, that Donaldbrec was slain in the fifteenth year of his reign in the battle of Strathcauin by Ohan, king of the Britons, and in the same, year a battle between Oswy and the Britons. The same transactions are repeated at a later date in Tighernac, when the first battle is said to have been in Calithros, and the second in Strathcarn, while the name of the British king is given as Haan; but the first are the true dates.

Donaldbrec was the king of Dalriada, and the son of that Aidan who had been defeated in 603. Glenmairison must not be confounded with the glen called Glenmoriston on Loch Ness. It was in Calithros, and Calithros appears to have been the same with the district called Calatria, in which Callander is situated. It

lay between the Carron and the Avon, extending on the west at least to the place called Carriden on the Avon, and bounded on the east by the Firth of Forth, including in its limits the parishes of Kineil and Careden; and within this district Glenmairison must have been situated, though it cannot now be identified. Etain was no doubt Eiddyn or Caereden, and the upper part of the valley of the Carron was called Strath Carron, in which there was a royal forest termed in old charters Stratheawin. These events then indicate a great struggle between Donaldbrec and the Britons, in which the former was defeated and finally slain in 642. If my conjecture is correct, that Aidan led a combined force of Scots and Britons, he was in fact for the time performing the functions of Guledig or "Dux Bellorum" in the north; and this struggle probably indicated an attempt on the part of Donaldbrec to maintain the same position. Who Ohan or Haan was, we do not know. He may have been a king of Alclyde and a successor of Rydderch, but it is more probable that he was no other than Cadwallawn himself, whom Tighernac calls Chon, and that the object of the war was whether Donald should retain his father's position, or whether Cadwallawn, who had now become powerful in the south, should extend his supremacy over the north likewise. 1

The great defeat of the combined forces of the Mercians and Britons in 655 by Oswy, king of Northumbria, in which Penda, king of the Mercians, was slain, and Cadwallawn escaped with his life, terminated the power of the latter, and led to the subjection of the Cumbrian Britons to the kings of Northumbria, and two years afterwards the Annals of Ulster record the death of Gureit or Guriad, king of Alclyde. The subjection of the Britons to the Angles lasted till the year 686, when Ecfrid, king of Northumbria, was slain in the battle of Dunnichen, and during that time no king of Alclyde is recorded. It was also during this time that Ecfrid granted to Lindisfarne, Carlisle, with territory to the extent of fifteen miles round it; but the result of the defeat and death of Ecfrid was, as Bede tells us, that a part of the Britons recovered their liberty, and that this part was the British kingdom of Cumbria or Strathclyde appears from this, that the kings of Alclyde again appear in the Annals as independent kings.

In 694 died Domnall MacAuin rex Alochluaithe, and, in 722, Beli filius Elfin rex Alochluaithe. In the Welsh pedigrees annexed to Nennius, a genealogy is given, in which this Beli, son of Elfin, appears, and his descent is there given from Dyfnwal Hen, the ancestor of Rydderch Hael, and stem-father of the second group of northern families.

Although the Britons of Strathclyde had recovered, their liberty, and the Picts had regained that part of the "Provincia Pictorum" north of the Forth which the

[paragraph continues] Angles had subjected, it would appear that the Pictish population south of the Forth still remained subject to them. The Picts of Manann had come under their power as early as the reign of Edwyn, and therefore still remained within the Anglic kingdom, as appears from their subsequently rebelling against its kings; and the Picts of Galloway seem likewise to have remained under their subjection, as Bede tells us that in 731, when he closes his history, four bishops presided in the province of the Northumbrians, one of whom was Pecthelm in the church which is called Candida Casa, or Whitehorn, "which," he says, "from the increased number of believers, has lately become an additional Episcopal see, and has him for its first prelate." This implies that Whitehorn still remained in the province of the Northumbrians; and in 750, we are told, in the chronicle annexed to Bede, that Ecbert, king of Northumbria, "Campum Cyil cum aliis regionibus suo regno addidit;" that is, Kyle and Carrick, which lay between it and Galloway, and possibly Cuningham, forming modern Ayrshire.

In the same year, however, a great battle is recorded both in the Welsh and the Irish Annals between the Britons and the Picts, in which the Picts were defeated, and Talorgan, brother of Angus, the king of the Picts, slain. The place where this battle was fought is termed in the Chronicle of 977, Mocetauc, in the Brut y Saeson, Magdawc, and in the Brut y Tywysogion, Maesydawc. Maes is the Welsh equivalent for Magh in Gaelic, meaning a plain, and the place meant was no doubt

[paragraph continues] Mugdock in the Parish of Strathblane, Stirlingshire, the ancient seat of the Earls of Lennox. In old charters it is spelt Magadavac. In the same year, according to the Welsh Chronicle, and two years after, according to Tighernac, died Teudwr, son of Bile, king of Alclyde, and in 756 Eadbert, king of Northumbria, and Angus, king of the Picts, appear to have united their forces, and we are told by Simeon of Durham that they le d their army "ad urbem Alewith, ibique Brittones inde conditionem receperunt, prima die mensis Augusti."

In 760 the Welsh Chronicle records the death of Dungual, son of Teudwr. From this date there is a blank in the kings of Alclyde for an entire century--the first notice we have of them again being in 872, when Arthga "rex Britonum Strathcluaide" is slain, "Consilio Constantini filii Cinadon." This Constantine was king of the Scots, and Arthga or Arthgal appears in the Welsh genealogy as descendant in the fourth degree from Dungual. Alclyde is recorded, however, in the Annals of Ulster as having been burnt in 780 and besieged 870 by the Norwegian pirates, who, after a siege of four months, took and destroyed it. According to the Welsh Chronicle, "Arx Alclut a gentilibus fracta est." Strathclyde was again ravaged by them in 875. Arthgal appears to have been succeeded by his son Run, who is called in the Pictish Chronicle "rex Britonum," and said to be the father of Eocha, who reigned along with Grig, by a daughter of Kenneth MacAlpin. This is the last name given in the Welsh genealogy, and one of the copies of the Brut y

[paragraph continues] Tywysogion has the following entry in 890, which, if containing a true fact, will explain this.

"The men of Strathclyde who would not unite with the Saxons were obliged to leave their country and go to Gwynned, and Anarawd (king of Wales) gave them leave to inhabit the country taken from him by the Saxons, comprising Maelor, the vale of Clwyd, Rhyvoniog, and Tegeingl, if they could drive the Saxons out, which they did bravely. And the Saxons came on that account a second time against Anarawd, and fought the action of Cymryd, in which the Cymry conquered the Saxons and drove them wholly out of the country; and so Gwynned was freed from the Saxons by the might of the 'Gwyr y Gogledd' or Men of the North."

That the British line of the kings of Strathclyde came to an end very soon is certain, for the Pictish Chronicle tells us that on the death of Donald "rex Britannorum," who must have died between 900 and 918, "Dunenaldus filiis Ede rex eligitur." He was brother to Constantine, the king of the Scots, and thus the Scottish line was established in the kingdom of Strathclyde. It must have been so much weakened by the loss of Kyle and the other regions wrested from it by the Saxons, and the attacks upon it by the Norwegian pirates, that we can well believe that, a large portion of the population fled to Wales for refuge, and that the influence of the new and powerful kingdom of the Scots led to a prince of that race being placed upon the throne.

In 946 it was overrun and conquered by Edmund, king of Wessex. He bestowed it upon Malcolm, king of the Scots, and from this time it became an appanage of the Scottish crown. The Saxon historians name the region conquered by Edmund as Cumbria, but that

this kingdom of Strathclyde is meant, appears from the Chronicle of 977, now a contemporary record, which has, in 946, "Strat Clut vastata est a Saxonibus."

It is unnecessary for the purpose of this work to follow the history further. Suffice it to say that, in the reign of Malcolm Canmore, Carlisle and that part of Cumbria south of the Solway Firth belonged to the Norman conqueror, and was erected into an earldom for one of his followers; that, on the death of Edgar, that part of it which lay north of the Solway Firth was given to his brother, Prince David, and on his accession to the throne in 1124 became united to the Scottish crown; but that its population remained a distinct element in the population of Scotland for some time after, under the names of Cumbrenses, Brits, and Strathclyde Wealas.

176:1 The Chronicle of 977 places Kentigern's death in 612; but the Aberdeen Breviary, in the Life of Baldred, places his death on Sunday, the 13th January 603. The 13th of January is St. Kentigern's day, and it fell upon a Sunday in 603 and also in 614. The first date is to be preferred.

178:1 The passages quoted from Tighernac will be found in the Chronicles of the Picts and Scots, recently published in the series of Scottish Records, and an account of Calatria will be found in the introduction, p. lxxx.