Sacred Texts Sacred Sexuality Index Previous Next

SEX worship being the most natural, the most personal or self-relating, and ever associated with physical maturity, we may safely conclude it to have had spontaneous origin in widely separated localities. As it arose in India it may have likewise arisen elsewhere. At all events, we believe India and the East are not the only places where the vestiges of it are found. There is reason to think the aboriginal people of California had phallic and yonigic usages, if those usages did not amount to a religious faith. In support of this view several stone relics of antiquity give evidence, if it be proper to base a conclusion upon the study of a few specimens.

The first of the kind it was my fortune to

Fig 25. |

C. C. Jones ("Antiquities of Southern Indians") says: "The worship of Priapus probably obtained among some of the Southern Indian nations. In the collection of Dr. Troost were many carefully carved representations in stone of the male organ of generation."

Another point worthy of note is the fact that the length of the so-called pestles exceeds that of nearly every other celt, as figured by Lubbock, Evans, or Jones.

[paragraph continues] The latter depicts a stone ax and handle in one piece, fifteen and three fourths inches long; a spade and handle, cut from solid rock, seventeen and a quarter inches long. Only one specimen has a length greater then the phalli; that is a flint sword which measures a little over twenty-one inches long.

Like all Gods, the parts which make the person are human or mundane; the divinity, thereof consists in office and proportion. To be godlike, those proportions must be exorbitant, as we not only here, witness, but as may be seen in most of the virile members figured on the bass-reliefs exhumed from the buried cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii. All present the same excess in the divine gift of magnitude--a never-failing attribute of the Almighty.

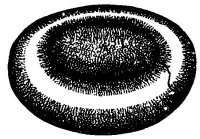

Fig. 26. |

of hammer or delving tool marks, which in the mortars proper these marks are very much effaced, as if by attrition of use. The base of the mortars have each a consistent flat bottom to rest on, while the underside of the celt in question is oval, making it unstable as an egg.

I find no diagram or description of a stone relic of this kind in Sir John Lubbock's "Prehistoric Times," Evans' "Stone Relies of England," or C. C. Jones, Jr.'s "Antiquities of Southern Indiana."

Though the direct evidence is small, the foregoing indirect evidence leads us to regard the relic purely a sacred emblem of the female type, answering to the yoni of India, and a companion to the phallus.