Sacred Texts Native American Maya Index Previous Next

Buy this Book at Amazon.com

Yucatan Before and After the Conquest, by Diego de Landa, tr. William Gates, [1937], at sacred-texts.com

They tattoo their bodies and are accounted valiant and brave in proportion to its amount, for the process is very painful. In doing it the craftsman first covers the part he wishes with color, and then delicately pierces the pictures in the skin, so that the blood and color leaves the outlines on the body. This they do a little at a time, on account of the pain and because of the disorders that ensue; for the places fester and form matter. But for all this they ridicule those who are not tattooed. They set much store on amiability and the showing of graces and natural accomplishments; today they eat and drink as we do.

The Indians are very dissolute in drinking and becoming intoxicated, and many ills follow their excesses in this way. They kill each other; violate their beds, the poor women thinking they are receiving their own husbands; they treat their own fathers and mothers as if they were in the houses of enemies; they set fire to their houses, and so destroy themselves in their

|

|

They often spend on one banquet all they have made by many days of trading or scheming. They have two methods of making these feasts; the first of these (that

|

and a cup, as fine as the host can afford. If one of the guests has died, the obligation to give the return invitation lies on his house or parents.

The other kind is between kinsfolk, when they marry

|

|

The Indians have delightful ways of entertainment; particularly they have actors who perform with great skill, to such an extent as that they hire themselves to the Spaniards for nothing other than to observe the jests the Spaniards pass with their servants, their wives, and on themselves over their good or bad serving; all of this they act later with as much art as attentive Spaniards could.

They have small drums which they strike with the hand, and another drum of hollow wood that gives a deep, mournful sound. This they hit with a longish stick at the end of which is a ball of a certain gum that exudes from a tree. They have long, thin trumpets of hollow wood, the end of which is formed of a large twisted gourd. They have another instrument made of a whole tortoise with its shells, from which the flesh has been removed; this they strike with the palm of the hand, giving a mournful, sad sound.

They have whistles of cane and of deer hones, also large conchs and reed flutes; with these instruments they accompany the dancers. Two of their dances are especially virile and worth seeing; one is a game of reeds, whence they call it colomché, the word having that meaning [a 'palisade of sticks']. To perform it they make a large circle of dancers, whom the music accompanies, and in time with which two come into the circle; one of these dances erect, holding a handful of reeds, while the other dances squatting, both keeping time around the circle. The one with the reeds throws them with all his force at the other, who with great skill catches them with a shall rod. them all are thrown they return, keeping time, into the circle, and others come out to do the same.

There is another dance in which 800 Indians, or more or less, dance with small flags in a great war measure, among all of them not one being out of

time. They are heavy in their dances, since they do not cease dancing for the entire day, food and drink being brought to them. The men do not dance with the women.

Click to enlarge

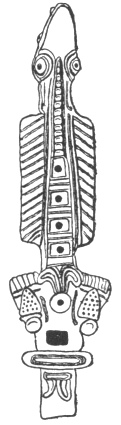

The tunkul or Mexican teponaztli; beaten with a rubber-tipped stick it can be heard for five or six miles.

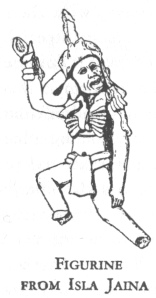

The other cuts show a musical Corn Festival as pictured in the Dresden Codex; a pax or Mexican huehuetl, to be beaten with the flat palms; a clay figurine of a dancer, from Isla Jaina, off the west coast; a deity seated on the earth, blowing a pipe (this and the pax from the Madrid Codex); a clay pipe in the form of a lizard.