Sacred-Texts Native American Inuit

Index Previous Next

[This tale seems to have its origin in historical facts, worked into a tale at a later period. Some parts of it allude to the struggles with the Indians, and the sudden attacks made by them on the Eskimo. Others most probably refer to the wars between the Eskimo tribes themselves, and to their distant migrations, by which they have peopled their wide territories. Several passages of this story are still frequently mixed up in different ways with other tales. The text has been constructed from three copies, in most particulars agreeing with each other.]

SEVERAL men had their permanent winter-quarters near the entrance to a fiord, and with them lived two boys, who were very officious and obliging. In the morning, when the men prepared to go out hunting, the boys helped to turn and rub their gloves, and made them ready for use, and likewise arranged the kayak implements and tools, and fetched the water for their morning drink. When the men had left, the boys exercised themselves in archery, and never entered the house the whole day long, until the men had returned, and they had assisted them in carrying their things from the beach. They did not even think of entering and partaking of their first meal till the last of the men had gone in, and they had once more fetched water. One evening in winter, by moonlight, when they had p. 133 gone out to draw water, the youngest said, "I think I see a lot of faces down in the water;" and Kunuk, the elder brother, replied, "Is it not the reflection of the moon?" "No, come and look for thyself;" and Kunuk looked into the water, and said, "Thou art right, they are getting at us;" and presently he observed in the water (viz., by way of clairvoyance) a host of armed men advancing towards them. The boys now ran as fast as possible and told everything to the people at home, but they only answered, "It must have been the moon that deceived you. Never mind, but run away and fetch us some water; the tub is empty." Off they went, but saw the same things over again, and went back to report it; but still they were not believed. But when they saw the armed men the third time advancing quickly towards them, they deliberated what to do with their little sister; and when they had determined to go and hide her, they entered the house and brought her outside; and seeing a heap of chips close to the window, they put her down, and covered her well up with them. Having done this, they went back and climbed the rafters beneath the roof of the house-passage; and in helping his brother to get up, Kunuk warned him not to get tired though he might find it an inconvenient place of refuge: they were keeping hold of one beam with their hands, and supported their feet against the next, and thus lay at full length, with their faces turned downwards. Presently a large man with a spear made his way through the entrance; after him another one appeared; and all told, they counted seven, who came rushing into the house. But as soon as they got inside a fearful cry was heard from those who were put to death by them. While they were still lingering inside Kunuk's brother was losing strength, and was nearly giving way, when the aggressors came storming out, fighting about, right and left, and flinging their spears everywhere, and likewise into the heap of chips, where p. 134 their little sister was lying. When the last of them had disappeared the younger boy fell to the ground, and Kunuk after him. When they came to look for their sister they found her struck right through the body with a lance, and with her entrails protruding; and on entering the house the floor was all covered with blood, every one of the inmates having been killed, besides one of the assailants. Being quite alone in the dreary house they would not stay, but left the place that very night, carrying their wounded sister by turns, and taking care that the entrails did not come out of their proper place. They wandered on for a long while in this manner, and at length they arrived at a firth, which was quite frozen over. There they went down on the ice, but on turning round a steep promontory their little sister died, and they buried her in a cave among the rocks. From the

beginning of their flight they exercised themselves in boxing and in lifting large stones to strengthen their limbs; and they grew on, and had become strong and vigorous men ere they again met with other people. After a great lapse of time they one day noticed a man standing on the ice beside a huge piece of wood, which he p. 135 had made use of in hunting the small seals. When they approached and told him what had befallen them, he said he would like to adopt them as his sons, and they followed him to a house where he and his wife lived all by themselves. Their foster-parents encouraged them never to forget their enemies, but always to be exercising themselves in order to strengthen their limbs. One night the brothers came home laden with ptarmigan and foxes, which they had caught without any weapons at all, only by throwing large stones at them, which made the old people rejoice very much, commending their dexterity and perseverance. To increase their strength still farther, they lifted very large stones with their hands only. They also practised boxing and wrestling; and no matter how hard the one might be pressing on the other, they made a point of never falling, but rolling together along the ground. At last, with constant practice, they had grown so dexterous that they could even kill a bear without any weapon. At first they gave him a blow, and when he turned upon them they took no more notice of him than if he had been a hare, but merely took hold of him by the legs and smashed him to pieces. When these results had been gained, they began to think of seeking out other people. Where? That was a matter of indifference. They now took a northerly direction, and wandered on a long way without falling in with any human being. At length they came to a great inlet of the sea, where a number of kayakers were out seal-hunting, but only one of them seemed to be provided with weapons. This one was their chief, or the "strong man" among them. He always wanted to harpoon the animals himself which had been hunted by the others—these had only to chase and frighten them; and if anybody dared to wound them, he was sure to be punished by the chief in person; but as soon as the "strong man" had pierced them with his arrow, the others all helped to kill them. Kunuk and p. 136 his brother were too modest to go down at once, and awaited the approach of evening. Meanwhile they witnessed the cutting up of a walrus, and saw it being divided—each person getting a huge piece for himself, excepting an old man, who lived in the poorest tent, who got nothing but the entrails, which his two daughters helped him to carry home from the beach. The brothers agreed that they would go to the old man when it had grown dark, because they had taken pity on him on account of his patience. Having arrived at the tent, Kunuk had to enter by himself, his brother being too bashful to follow him. The old man now inquired of him, "Art thou alone?" "No, my little brother is standing outside; he is ashamed to enter." On hearing this, the old man cried, "Come in, thou who art standing outside;" and when he entered, he was astonished to see his strong limbs, he being even bigger than his brother. When the meal was over the old man said he would like to have them for his sons-in-law, and that they might go and take his daughters for their wives. Kunuk chose the youngest of them, and his brother got the eldest; and thus they got married. It is said that while going down to the place, they first went to have a look at the boats, and examined them closely; and that on seeing the weapons of the "strong man," they had taken his javelin (or arrow to be flung only by hand) away, with the intention of hiding it, so that the others might get something to look for. They brought it away to a spring, and a little way off they stuck it down into the earth, but pulled it out again, trying another place, where the turf was dry and hard. There Kunuk fixed it so deep in the ground that only so much of it as could be seized with two fingers was to be seen. While they were lying down inside the tent, they heard some one come running along, and partly lift the curtain, but instantly drop it and go off again. It was an old gossip, and mother to the "strong man," who had p. 137 been doing this; and a moment later a multitude of people gathered round the entrance of the tent, to get a peep at the strangers. In the morning they heard the chief crying out, "This is a fine day for a walrus-hunt;" upon which he was silent a while, and then said, "My javelin has been taken away," which was repeated again and again by many others. When Kunuk emerged from the tent he saw several of the men coming out rubbing their eyes, and saying, "I must surely have slept too long!" However, it was only out of reverence for the "strong man" that they spoke thus. While they were shouting, they heard the old gossip, who had been away to fetch water, exclaim, "Look, yonder is the javelin!" and at the same time she pointed to the rock leading to the spring. All of them now rushed to the spot, in order to pull it out of the earth, but nobody succeeded in doing it. The brothers were now called, and were asked to draw it out. They had all been pulling and biting it with their teeth to get it loose, so that the end had been quite wasted. But Kunuk just took it between his two fingers, and disengaged it as if it were a very small matter. On their way down to the shore their father-in-law addressed them, and said, "Down there, underneath the great boat, are the two kayaks of my dead son. They are perfectly fitted up, and furnished with weapons, and are quite easy to get at." These things he now wanted to make over to his sons-in-law, and he told them that the "strong man" had murdered his son because he envied him his still greater strength; for this reason he was now the enemy of his daughters. Hitherto, however, they had not been able to get their revenge. After a short interval the cry was heard, "Let the strangers come on for a boxing and fighting match on the great plain up yonder;" upon which all the men made thither to behold the spectacle. The brothers followed them; and arriving at the place, they saw a pole set up on end, and beside it the leader standing with a p. 138 whip made of walrus-skin, with a knot on the end. There was also a stuffed white hare, and whenever anybody set foot on it, he quickly lashed them with the whip. Kunuk was the first who advanced towards the hare, and the chief tried to hit him, but did not succeed in reaching

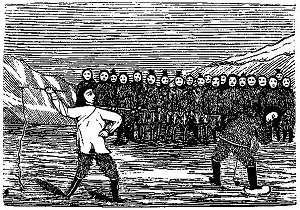

him. Soon after, Kunuk courageously put his foot on the hare; but the very moment the "strong man" lifted up his whip Kunuk stooped down and hardened his limbs (by charm), and when the other smote him the whip gave a loud crack. The "strong man" now believed that he had killed Kunuk, who nevertheless came away unhurt. When the crack of the thong was heard, the "strong man" ordered the younger brother to step forward. He, however, cared less than Kunuk: and after the first attempt the chief proposed that he should take the whip for a change; and giving it to him, he went himself and put his foot on the hare. Kunuk's brother now cried, "Look out and harden thy body!" but at the same time smote him, so that he p. 139 fell down dead on the spot. All his inferiors now rejoiced greatly, and called out to the brothers, "Henceforth ye shall be our leaders!" but they rejoined, "In future ye shall have no masters, but hunt at liberty and at your own will." The brothers now practised all manner of feats belonging to kayaking and seal-hunting, and procured themselves bladder-arrows1—the bladders being made out of one entire blown-up seal-skin. One day they joined some other kayakers, and went in pursuit of a very large she-walrus. Kunuk lanced it four times at a greater distance than usual, and his arrow went right through the animal, which, panting for breath, after a minute or two was quite dead. When the others came on to give it the finishing stroke, they found that the arrow had penetrated to the very vent-holes of the bladder; and they all rejoiced at his great dexterity, and praised it highly. Ordinary seals even grew quite stiff when his spear merely grazed them. He once heard a report of a very giant, who lived southward, and was named Ungilagtake.2 He had a huge sword, and nobody was ever known to escape him; even the most valiant of men were vanquished and put to death by him. On hearing this, the brothers immediately supposed him to have been among the strong armed men who attacked their housemates at home, when they themselves were still little children; and they at once determined to go and find him out, knowing that they were now more capable of revenging themselves than they had been at that time. They left the place in two boats, one of which belonged to the youngest; in this the mother of the "strong man" who had been killed accompanied him. The other boat was Kunuk's, and many kayaks went along with them to make war against Ungilagtake. A pretty strong breeze from p. 140 the north had sprung up, and the boats hoisted their sails, and the kayak-men amused themselves with throwing their harpoons alongside the boats. It so happened that Kunuk, in flinging the harpoon, hit the prow of the boat, so that it rebounded into the water with a great splash. On seeing this, the old hag chuckled, and went on mocking and teasing the wife of Kunuk till she could not help crying; and Kunuk asked his brother, who was in command of the boat, "Why is my wife crying?" "Oh, that's on account of the arrow," he answered; "she is so mortified because the old woman laughed at thee." Kunuk now purposely dropped astern a little, and holding his harpoon ready, suddenly pushed forward, and flung it across the boat, so that it hit the hood of the old woman's fur coat, while she sat rowing in the fore-end of the boat, even tearing a piece out of it; and this trick he repeated once more. After a while, Kunuk's brother turned his looks towards land, and recognised the burial-place of their little sister. This made him very sad, and he asked for some one to relieve him at the helm, he wanting to go and sit down forward, where, bent down, he went on sobbing, and vainly striving to keep back his tears, while the water from the sea came into the boat, which kept swinging and tossing from his convulsions. He took ill from that very day, and died before they reached their destination, so that Kunuk came alone to Ungilagtake. It was in the depth of winter, and they were met by many people on the ice. A somewhat biggish man invited them to come and put up at his house. This man likewise happened to be an enemy of Ungilagtake; and as soon as the guests had entered, he told them that before the meal he would show them how Ungilagtake used to behave to strangers. He took an entire seal-skin, stuffed with sand, and to the centre of which a strap was attached. Into this he put his third finger, and carried it round the room, after which he ordered his guest to do the same. Kunuk p. 141 took hold of the strap with his little finger, lifted the thing with unbent arm, and put it down without being fatigued. The host then went on, "Now sit down opposite to me, and I will throw a lance at thee, which, however, won't hurt thee;" upon which he brought out a lance and a drum, and began singing, while Kunuk heard the others saying, "Bend thee down, stranger!" Kunuk at once complied, so that nothing but his chin was visible; and when his host threw the lance at him, he lost his aim, merely observing, "This is the way of Ungilagtake, who always hits the mark, and never fails. Yet I don't know how thou wilt fare with him; he will hardly be able to molest thee. But then he has a companion, called Tajangiarsuk, with a double back, being as fat in front as behind, who is immensely strong, and gives him a hand if there happen to be any one he cannot master." Whilst they were sitting down at the meal a cry was heard without, "Ungilagtake invites the stranger to his house!" When Kunuk and his wife were preparing to go, the host said, "Now make a bold entrance, or he will be sure to kill thee at once." The visitors now went up to a large house with three windows, which was occupied with Ungilagtake's numerous wives—all of whom he had stolen. Kunuk was ordered to sit down on the side bench, but his wife was brought to a seat on the main ledge, and their former host placed himself opposite her husband. Many other spectators now entered; but whenever a new visitor made his appearance, Kunuk asked his first host if that were Tajangiarsuk, until at last he too arrived. Refreshments, consisting of various dishes, were now served before them; and when they had finished eating, Ungilagtake ordered Kunuk to seat himself opposite to him, and presently drew out a huge spear from beneath the bench, and striking upon the drum, which had likewise been produced, the whole joined in a song for Kunuk, at the same time crying out, "Bend thee down, stranger that p. 142 has come among us; the great Ungilagtake, who never missed his aim, is going to thrust his spear at thee." He bent down as before, so that only his chin appeared; but whilst Ungilagtake was taking aim at him, he nimbly gave a jump, and caught hold of one of the roof-beams, while the spear went far below him; and when it was flung at him the second time, he quickly jumped down, and the spear came flying above him, amid great cheers from the spectators. When Ungilagtake was about to take aim the third time, Kunuk seized the spear, saying that he, too, would like to have a try at killing with it. They now exchanged places. Kunuk, beating the drum, now struck up a song for Ungilaktake; but the very moment the latter was preparing to bend his back, Kunuk had already taken aim at him, and the spear hit him in the throat, so that he fell dead on the spot. Everybody now rushed out of the house, and Kunuk was following, but soon found himself seized from behind by some one, who proved to be Tajangiarsuk. A wrestling-match soon ensued on a plain of ice, covered with many projecting stones, which he had chosen on purpose, in order to finish off his adversaries by dashing them against the stones. Kunuk felt a little irresolute when he noticed that he had found his equal. However, he took hold of him, and tried to lift him up before he got tired out. He flung him down on the ground, so that the blood gushed out of his mouth. Another champion soon made his appearance, who was of a still stronger and larger make; and he soon got Kunuk down, and had already put his knee on the heart of Kunuk, when the latter suddenly took hold of him from beneath, grasped his shoulders, and pressed the lungs out of him. The applause of the spectators was again heard, while some of them were crying, "Now they are bringing the last of the lot, him with the lame legs;" and soon after three boats were seen to carry this champion thither, for he was not like ordinary men, but p. 143 of an immense size, so that he was obliged to lie across all three boats to get along. Having reached the landing-place, he crept up to the combat-field on his elbows. When Kunuk tried to throw him, his legs never moved an inch; but when he proceeded to lift him up by taking hold of him round the waist, and began to whirl him round, he gradually succeeded in lifting also his feet; and when they at last turned right outwards, to let him fall in such a way that his skull was crushed. The people rejoiced, and cried, "Thanks to thee! now we shall have no masters!" and those who had been robbed of their wives got them back again.

1 Small harpoons with a bladder attached to the shaft, but without any line, and principally used for small animals.

2 Pron. Unghilagtakee.