Sacred Texts Freemasonry Index Previous Next

Buy this Book on Kindle

Symbolical Masonry, by H.L. Haywood, [1923], at sacred-texts.com

The Book of Constitutions. During the period lying, say, between 1000 and 1400, when Operative Freemasonry was enjoying its plenitude of power, it is probable that no written constitutions were in use. According to such meagre evidence as we possess it seems that the candidate, at the time of his initiation, was given an oral account of the traditional history of the Craft and that the Master gave him the charges of instruction and duty in such language as he might choose to employ at the time. As would inevitably happen under such circumstances these traditions and charges gradually assumed a more or less stereotyped form until at last, to make uniformity more certain, they were committed to writing.

The oldest MS. form of the Old Charges now in existence, as I have already noted, is that which was written by some unknown cleric somewhere near the year 1390; it is known as the Regius, or Halliwell MS., and is written in the form of doggerel verse. Our next oldest copy is the Cooke, which was written early in the following century. Many copies were made of these from time to time, and other versions of the Craft's story were composed; through the labours of Brother W. J. Hughan, the great pioneer in this field, and through the efforts of his colleagues we now possess close on to a hundred copies of these old documents.

Many copies of the Old Charges were in the hands of brethren in the beginning of the eighteenth century.

[paragraph continues] When the Revival came, and outsiders began to probe into the secrets of the Order certain of these brethren, to guard against their falling into strange hands, burned several of their manuscripts. Not all, however, were destroyed, and it appears that an attempt to collate the Ancient Constitutions was made as early as 1719.

Shortly after the formation of Grand Lodge some members expressed dissatisfaction with the existing Constitutions and Grand Master Montagu ordered Dr. James Anderson to make a digest of all available manuscripts in order to draw up a better set of regulations for the governance of the body. It is thought by some that it was Dr. Anderson himself who first urged this on Montagu. A committee of fourteen "learned brethren" examined Anderson's work and approved of it, except for a few amendments, and it was accordingly published in the latter part of 1723. This Book of Constitutions "is still the groundwork of Masonry" and stands to our jurisdictions very much as the Constitution of the United States does to our nation.

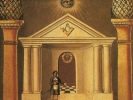

Holding such a position it is fitting that the Book of Constitutions serve as a symbol in the Third Degree. Being, as it were, the title deed of our Fraternity it is much more than a mere instrument of law, and links us on to the great past and binds us in an organic unity to the generations of old builders who, in departing this life, left behind them so shining a monument. As a symbol, therefore, the Book of Constitutions reminds us of our debt to the past, of our solidarity with the vanished generations of kindly workmen, and of the necessity of law and of seemly order if the Craft is to hold itself together in a world where everything is always falling to pieces.

The Tiler. If the Tiler is set to guard the Book, it is to remind us that secrecy and watchfulness must ever be at hand to guard us against our enemies, for the Tiler is here introduced as a symbol rather than as an officer of the lodge. When the Craft first began to employ such a sentinel we know not, nor can we be sure how the word itself originated. Some believe that the first tiler was literally what the word implies, a brother employed to make roofs, himself a member of one branch of the old guilds of builders. Others think that as the sentinel is to protect the secrecy of the lodge he was called tiler in a figurative sense since it is the roof which conceals the interior of a building. Accepting such views for what they are worth, and acknowledging the practical necessity for such a guardian, we may also see in the Tiler, in the present connection, a reminder that each and every one of us must become a watchman, seeing to it that no influence shall undermine our organic law, and that no enemies shall be permitted admittance to our fellowship. Every loyal Mason must be a Tiler, watchful lest he recommend an unfit candidate, and careful lest, in his own person, he admit such influences into the lodge as make for disunion and disharmony. To keep off cowans and eavesdroppers, figurative and actual, is one great duty of membership.

Cowan is a Scotch term. It was used in early Scotch Masonry in more than one sense but seems originally to have meant "a man who uses round unsquared stones for building purposes, whether walls or huts"; in other words, the cowan was originally an unskilled Mason. Oftentimes a cowan was loosely affiliated with the Craft but never given its secrets, for which reason he was often known as a "Mason without the word." The term was

also employed to describe a non-affiliated skilled Mason, one who had unlawfully obtained the secrets of the Craft—as we would say, a scab.

The word was employed by English Masonry in the Grand Lodge period; Brother J. T. Thorp believes it was Dr. Desaguliers who first used it after his visit to Scotland in 1721; Brother Vibert believes it was imported by Dr. Anderson in 1723 or later. Be that as it may the word found a permanent place in our vocabulary albeit with gradual changes of meaning. Literally speaking, as the word is now employed, a Cowan is a man with unlawful Masonic knowledge; an Intruder is one with neither knowledge nor secrets who makes himself otherwise obnoxious; a Clandestine is one who has been initiated by unlawful means; an Irregular is one who has been initiated by a lodge working without authorisation. In all these senses a man is designated who makes use of the Fraternity in an illegal or obnoxious manner, who uses Masonry for un-Masonic purposes. Manifestly such men cannot be kept out by the Tiler alone; every member must assist in this work of the guardianship of the Order.

Sword Pointing to the Naked Heart. Mackey notes that in old initiation ceremonies, still preserved in some places, the candidate found himself "surrounded by swords pointing at his heart, to indicate that punishment would duly follow his violation of his obligation"; he suggests that in this old ceremony we may find the origin of the present symbol which has been undoubtedly introduced into our system by some modern ritualist, Thomas Smith Webb, perhaps. This is a reasonable account of the matter and may be allowed to stand until further light is available.

The Heart is here the symbol of conscience, the seat of man's responsibility for his own acts; the Sword is the symbol of Justice. The device therefore tells us that Justice will at last find its way to our inmost motives, to the most hidden recesses of our being. This may sound trite enough but the triteness must not blind us to the truth of the teaching.

For centuries men believed that God, the Moral Lawgiver, lived above the skies and dealt with his children wholly through external instruments;—agents of the law, calamities, and physical punishments, such things as these were considered the Divine methods of administering Justice. Entertaining such a view of the matter it is of little wonder that men held themselves innocent until punishment would come, or that Justice could be avoided simply by staying clear of the instruments of Justice. In this wise Morality came to be an external mechanical thing, operating like a civil code of law which depends on policemen.

But now we have a better understanding of the matter. The Moral Law, so we have learned, is in our very hearts, and it is self-executing. Sin and punishment, as Emerson says in his great essay on Compensation, a profoundly original and stimulating study of the subject, grow from the same stem. Conscience, like the physical body, is under a universal Reign of Law that swerves not by a hair's breadth. A man may cherish an evil thought in some chamber of his soul almost outside the boundaries of his own self-consciousness, but such secrecy is of no avail; the law is in the secret places as well as in the open and always does the point of the Sword rest against the walls of the Heart. The penalties of Justice are unescapable because Justice and Conscience are of the same root.