Sacred Texts Miscellaneous Index Previous Next

Buy this Book at Amazon.com

Mazes and Labyriths, by W. H. Matthews, [1922], at sacred-texts.com

READERS of our previous chapters will have noticed the frequency with which the name "Troy" is associated with the idea of the labyrinth.

We find this association, for instance, in the case of the "Troy-towns" of Somerton and Hillbury, the "Walls of Troy" of the Cumberland Marshes and Appleby (Lincs), and the "Caerdroia" of the Welsh shepherds. In northern Europe we find it as "Troja" or in such combinations as "Trojeborg" or "Tröborg."

That this association is not of recent origin we have an interesting token in a reference which occurs in a fifteenth-century French manuscript preserved in the British Museum. This manuscript is the record of a journey made by the Seigneur de Caumont to Jerusalem in 1418, and is entitled "Voyaige d’oultremer en Jhérusalem." Calling at the island of Crete en route, the Seigneur, like most other travellers on similar occasions, takes occasion to make a few remarks about the famous legend associated with it. He speaks of the "mervelleuse et orrible best qui fut appellé Minotaur," who, he says, was confined within "celle entrigade meson faite par Dedalus, merveilleux maquanit, lequelle meson fut nominée Labarinte et aujourduy par moultz est vulguelmant appellé le cipté de Troie."

It would seem from the latter observation that the expression "Troy-town" or "City of Troy" was in general use 500 years ago as a title for the

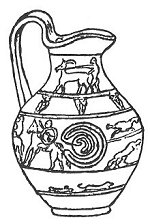

FIG. 133.—Etruscan Wine-vase from Tragliatella. (Deecke.) |

We find the name of Troy definitely associated with the labyrinth long before this, however, in the crude engravings on the Etruscan wine jar which we noticed in Chapter VIII., the oinochoë from Tragliatella.

The meaning of these figures (Figs. 133, 134 and 135) has been much discussed, but it is now generally agreed that the labyrinth shown has a close relationship with the operations which are being performed by the group of armed men, and it is obvious that it is also connected in some way with the

Click to enlarge

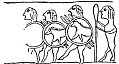

FIG. 134.—Etruscan Vase. ''Troy Dance'' Details. (Deecke.)

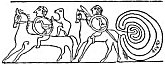

famous story of the wars of Troy, as we see by its label "Truia." What is this operation in which the warriors are engaged? We find a helpful clue in the story

related by Virgil (B.C. 70-19) in his great epic of the Aeneid, in which the poet has embalmed for us the legends current in his time concerning the wanderings of Aeneas, the reputed son of Anchises and Venus, after the fall of the city of Troy, which he had fought bravely to defend.

Aeneas, who escaped from the city carrying his father on his shoulders, led forth also his little son Iulus. It is this boy whom, in the fifth book of the poem, Virgil pictures as taking part with his companions in a sport called the Ludus Trojae or Lusus Trojae (Game of Troy), sometimes

Click to enlarge

FIG. 135.—Etruscan Vase. Details, showing Labyrinth and ''retroscript'' label—''TRUIA.'' (Deecke.)

simply Troja. According to the Roman tradition it was introduced into Italy by Aeneas, and his son Ascanius imparted it to the Alban kings and through them to the Romans. The game consisted of a sort of processional parade or dance, in which some of the participants appear to have been mounted on horseback. Virgil draws a comparison between the complicated movements of the game and the convolutions of the Cretan Labyrinth:

"As when in lofty Crete (so fame reports)

The Labyrinth of old, in winding walls

A mazy way inclos’d, a thousand paths

Ambiguous and perplexed, by which the steps

Should by an error intricate, untrac’d

Be still deluded."

(Trapp's trans., 1718.)

The game is also mentioned as a well-established institution by other Roman writers of a century or so later, such as Suetonius and Tacitus, and appears to have assumed imposing dimensions at one time, as we see from a representation of it on the reverse of a medal of Nero, where it has more of the nature of a military review. It was generally performed by youths, and only those of good social standing took part.

It will be remembered that we have already had occasion to notice another ancient dance, or game, in which youthful notabilities were stated to have taken part, and in which the motions of the dances were supposed to represent the tortuous paths of the Cretan Labyrinth, namely, the dance performed by Theseus and his friends on the island of Delos. This dance was called the "Geranos," or Crane Dance, probably on account of the fancied resemblance of the attitude of the dancers to that of cranes in flight, or perhaps on account of actual adornments of the dancers. (An eighteenth-century German traveller in Russia relates that the Ostiaks of Siberia had an elaborate Crane Dance, the dancers being dressed up in the skins of those birds.)

Is there any connection between these two dances, both labyrinthine in character, the one traditionally based on the windings of the labyrinth of Knossos, the other compared by Virgil with the latter, but named after another city famous in ancient legend—to wit, Troy?

In regard to both these cities the events celebrated in the classic legends were of prehistoric occurrence (in so far as they occurred at all), and their recital was handed down orally for very many generations before they

became crystallised in the written record, and it is not therefore surprising if during that time various versions were evolved and discrepancies of person, place, and time were introduced.

The association of the labyrinth, by some of the Nordic Aryan peoples, with Troy instead of Knossos may perhaps be accounted for in this way.

The point with which we are most concerned at the moment, however, is the fact that the figure of the labyrinth, in each case, is connected with the idea of a ceremonial game or dance.

Another dance, possibly of similar character, associated with Knossos, is that mentioned in Homer's "Iliad" as having been invented by Daedalus for Ariadne. Youths with golden swords and maidens crowned with garlands performed it in ranks.

By analogy with a great number of myths, rites, and ceremonies of ancient and modern races, some anthropologists have been led to the conclusion that these Troy and labyrinth dances are only particular expressions of a very early and widely diffused ceremonial associated with the awakening of nature in spring, after its winter sleep, or the release of the imprisoned sun after its long captivity in the toils of the demon of winter.

In that marvellous compendium of universal folk-lore "The Golden Bough," and in the particular volume of it entitled "The Dying God," Sir James Frazer debates the significance of the classic legends we have mentioned, and draws the tentative conclusion that Ariadne's dance was symbolical of the sun's course in the sky, its intention being, "by sympathetic magic to aid the great luminary to run his race on high." (See also p. 92.) He draws attention to a practice observed by Chilcotin Indians, during eclipses of the sun, of walking around a circle leaning on staves, as if to help the sun around its course (much as a child pushes the partition of a railway compartment to help the train along).

Mr. A. B. Cook, the Cambridge classical archaeologist, points out in this connection a Knossian coin on which the Minotaur, or rather, a man with a bull's mask, is shown engaged apparently in a similar rite, the reverse being occupied by a "swastika" labyrinth.

All this appears highly speculative to the ordinary layman, but nobody who gives a little attention to the subject can avoid the conclusion that at any rate there must have existed in very early—possibly Neolithic—times an extremely widespread and important ceremonial, generally of a sacrificial type, in connection with the spring awakening. So deeply seated was this ancient tradition that traces of it have persisted, with various local modifications, right down to the present day.

The sword-dances and morris-dances of our own country, most of which but for the happy genius and industry of Mr. Cecil Sharp and his disciples would have passed away entirely by the next generation, are undoubtedly survivals of a ceremonial of this type, particularly the former. They were performed only on certain fixed annual occasions, and were treated with great reverence and meticulous attention to detail.

A correspondent writing to Notes and Queries in 1870 (Anne Silvester) laments the fact that "the old British game of troy, the vestiges of which are so rare," is becoming extinct, but does not describe it. No doubt the writer had in mind some game played in connection with earth mazes.

It is a pity that we have no record of the actual method of "running the maze" in this country in past generations. The idea that such ingeniously designed and care-fully constructed works were made for the sole purpose of trotting along their convolutions to the centre and out again, without any symbolic or religious significance or any ceremonial observance, may be dismissed at once.

As regards their alleged use by the Christian Church

for purposes of penance, we have no reliable evidence, and even if we had we know that such a use would have been of a secondary character. Most probably they were appropriated to some seasonal observance, as in fact we know that several of them were within quite recent years, and were associated with some ritual dance similar in nature to the Crane Dance or the Dance of Troy. With regard to the word "Troy" itself there is a possibility that its connection with the dance and the labyrinth figure may have originated not with the name of a town, but with some ancient root signifying to wind, or turn; in the case of the Welsh "Caerdroia," as we have already seen, this suggestion was made long ago. It may also have some connection with the three-headed monster Trojano of the ancient Slavonic mythology, who appears in the Persian legends as Druja, or Draogha, and in the Rig-Veda of India as Maho Druho, the Great Druh, and who plays throughout the same part as the wintry demon Weyland Smith (or Wieland) of the northern traditions. In Iceland, as we have already seen (p. 150), the earth mazes are associated with the latter personage.

We find the word Troi, or Troi-Aldei, applied to certain ceremonial parades akin to the Troy-dance, in the writings of Neidhart von Reuenthal, in the early thirteenth century, the accompanying songs being termed "Troyerlais."

Quite recently a contributor to "Folk Lore" gave the airs of three popular dances which are performed by the Serbians at the present day under the names of Trojanka and Trojanac. The correspondent in question had thought that their names might have some connection with the root tri (= three), with reference to the rhythm of the dances, but the airs supplied by him certainly would not support this contention. It is far more probable, as he seems to conclude, that they indicate a connection with the Dance of Troy. Unfortunately he does not describe the dances themselves; it would be interesting to

know whether they embody any movements suggestive of a labyrinthine origin or corresponding to the dances described by Homer and Virgil on the one hand, or to our morris and sword dances on the other.

Another point in this connection which might justify a little enquiry is the question of the origin of that maze-figure which forms, or used to form, part of the system of Swedish drill as taught to children in this country.

With regard to our native dances mentioned above, we may note that every care has been taken by competent investigators to discover and to preserve as much as possible of the pure tradition, and we have the satisfaction of knowing that, narrowly as they escaped oblivion, the English Folk-Dance Society will see to it that such a danger will not threaten them again for a very long time.