Sacred Texts Classics Homer Index Previous Next

HOW ODYSSEUS LEFT CALYPSO’S ISLAND AND CAME TO THE LAND OF THE PHÆACIANS: HOW HE TOLD HE FARED WITH THE CYCLOPES AND WENT PAST THE TERRIBLE SCYLLA AND CHARYBDIS AND CAME TO THE ISLAND OF THRINACIA WHERE HIS MEN SLAUGHTERED THE CATTLE OF THE SUN: HOW HE WAS GIVEN A SHIP BY THE PHÆACIANS AND CAME TO HIS OWN LAND: HOW HE OVERTHREW THE WOOERS WHO WASTED HIS SUBSTANCE AND CAME TO REIGN AGAIN AS KING OF ITHAKA

EVER mindful was Pallas Athene of Odysseus although she might not help him openly because of a wrong he had done Poseidon, the god of the sea. But she spoke at the council of the gods, and she won from Zeus a pledge that Odysseus would now be permitted to return to his own land. On that day she went to Ithaka, and, appearing to Telemachus, moved him, as has been told, to go on the voyage in search of his father. And on that day, too, Hermes, by the will of Zeus, went to Ogygia--to that Island where, as the Ancient One of the Sea had shown Menelaus, Odysseus was held by the nymph

|

Beautiful indeed was that Island. All round the cave where Calypso lived was a blossoming wood--alder, poplar and cypress trees were there, and on their branches roosted long-winged birds--falcons and owls and chattering sea-crows. Before the cave was a soft meadow in which thousands of violets bloomed, and with four fountains that gushed out of the ground and made clear streams through the grass. Across the cave grew a straggling vine, heavy with clusters of grapes. Calypso was within the cave, and as Hermes came near, he heard her singing one of her magic songs.

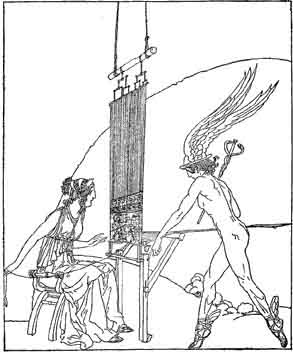

She was before a loom weaving the threads with a golden shuttle. Now she knew Hermes and was pleased to see him on her Island, but as soon as he spoke of Odysseus and how it was the will of Zeus that he should be permitted to leave the Island, her song ceased and the golden shuttle fell from her hand.

‘Woe to me,’ she said, ‘and woe to any immortal who loves a mortal, for the gods are always jealous of their love. I do not hold him here because I hate Odysseus, but because I love him greatly, and would have him dwell with me here,--more than this, Hermes, I would make him an immortal so that he would know neither old age nor death.’

‘He does not desire to be freed from old age and death,’ said Hermes, ‘he desires to return to his own land and to live with his dear wife, Penelope, and his son, Telemachus. And Zeus, the greatest of the gods, commands that you let him go upon his way.’

‘I have no ship to give him,’ said Calypso, ‘and I have no company of men to help him to cross the sea.’

‘He must leave the Island and cross the sea--Zeus commands it,’ Hermes said.

‘I must help him to make his way across the sea if it must be so,’ Calypso said. Then she bowed her head and Hermes went from her.

Straightway Calypso left her cave and went down to the sea. By the shore Odysseus stayed, looking across the wide sea with tears in his eyes.

She came to him and she said, ‘Be not sorrowful any more, Odysseus. The time has come when thou mayst depart from my Island. Come now. I will show how I can help thee on thy way.’

SHE brought him to the side of the Island where great trees grew and she put in his hands a double-edged axe and an adze. Then Odysseus started to hew down the timber. Twenty trees he felled with his axe of bronze, and he smoothed them and made straight the line. Calypso came to him at the dawn of the next day; she brought augers for boring and he made the beams fast. He built a raft, making it very broad, and set a mast upon it and fixed a rudder to guide it. To make it more secure, he wove out of osier rods a fence that went from stem to stern as a bulwark against the waves, and he strengthened the bulwark with wood placed behind. Calypso wove him a web of cloth for sails, and these he made very skilfully. Then he fastened the braces and the halyards and sheets, and he pushed the raft with levers down to the sea.

That was on the fourth day. On the fifth Calypso gave him garments for the journey and brought provision down to the raft--two skins of wine and a great skin of water; corn and many dainties. She showed Odysseus how to guide his course by the star that some call the Bear and others the Wain, and she bade farewell to him. He took his place on the raft and set his sail to the breeze and he sailed away from Ogygia, the island where Calypso had held him for so long.

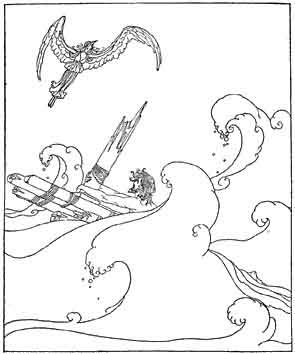

But not easily or safely did he make his way across the sea. The winds blew upon his raft and the waves dashed against it; a fierce blast came and broke the mast in the middle; the sail and the arm-yard fell into the deep. Then Odysseus was flung down on the bottom of the raft. For a long time he lay there overwhelmed by the water that broke over him. The winds drove the raft to and fro--the South wind tossed it to the North to bear along, and the East wind tossed it to the West to chase.

In the depths of the sea there was a Nymph who saw his toils and his troubles and who had pity upon him. Ino was her name. She rose from the waves in the likeness of a seagull and she sat upon the raft and she spoke to Odysseus in words.

‘Hapless man,’ she said, ‘Poseidon, the god of the sea, is still wroth with thee. It may be that the waters will destroy the raft upon which thou sailest. Then there would be no hope for thee. But do what I bid thee and thou shalt yet escape. Strip off thy garments and take this veil from me and wind it around thy breast. As long as it is upon thee thou canst not drown. But when thou reachest the mainland loose the veil and cast it into the sea so that it may come back to me.’

She gave him the veil, and then, in the likeness of a seagull she dived into the sea and the waves closed over her. Odysseus took the veil and wound it around his breast, but he would not leave the raft as long as its timbers held together.

|

For two nights and two days he was tossed about on the waters. When on the third day the dawn came and the winds fell he saw land very near. He swam eagerly towards it. But when he drew nearer he heard the crash of waves as they struck against rocks that were all covered with foam. Then indeed was Odysseus afraid.

A great wave took hold of him and flung him towards the shore. Now would his bones have been broken upon the rocks if he had not been ready-minded enough to rush towards a rock and to cling to it with both hands until the wave dashed by. Its backward drag took him and carried him back to the deep with the skin stripped from his hands. The waves closed over him. When he rose again he swam round looking for a place where there might be, not rocks, but some easy opening into the land.

At last he saw the mouth of a river. He swam towards it until he felt its stream flowing through the water of the sea. Then in his heart he prayed to the river. ‘Hear me, O River,’ was what he said, ‘I am come to thee as a suppliant, fleeing from the anger of Poseidon, god of the sea. Even by the gods is the man pitied who comes to them as a wanderer and a hapless man. I am thy suppliant, O River; pity me and help me in my need.’

Now the river water was smooth for his swimming, and he came safely to its mouth. He came to a place where he might land, but with his flesh swollen and streams of salt water gushing from his mouth and nostrils. He lay on the ground without breath or speech, swooning with the terrible weariness that was upon him. But in a while his breath came back to him and his courage rose. He remembered the veil that the Sea-nymph had given him and he loosened it and let it fall back into the flowing river. A wave came and bore it back to Ino who caught it in her hands.

But Odysseus was still fearful, and he said in his heart, ‘Ah me! what is to befall me now? Here am I, naked and forlorn, and I know not amongst what people I am come. And what shall I do with myself when night comes on? If I lie by the river in the frost and dew I may perish of the cold. And if I climb up yonder to the woods and seek refuge in the thickets I may become the prey of wild beasts.’

He went from the cold of the river up to the woods, and he found two olive trees growing side by side, twining together so that they made a shelter against the winds. He went and lay between them upon a bed of leaves, and with leaves he covered himself over. There in that shelter, and with that warmth he lay, and sleep came on him, and at last he rested from perils and toils.