Sacred Texts Freemasonry Index Previous Next

Buy this Book on Kindle

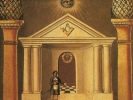

Symbolical Masonry, by H.L. Haywood, [1923], at sacred-texts.com

The Mackey Encyclopædia article on this subject is very brief, as may be seen from the following: "A mode of recognition so called because of the rude resemblance made by the hand and fingers to a lion's paw. It refers to the 'Lion of the tribe of Judah.'" This is true as far as it goes, but it doesn't go far enough, for it leaves unanswered the questions of origin and interpretation. Nor does the companion article on the "Lion of the Tribe of Judah" give us much more information. If Mackey refrained from saying more because he knew no more we can sympathise with him, seeing that at this late day there is still very little known about the matter. But we have learned something since Mackey wrote, enough maybe, to set us on the track toward a satisfactory understanding of the matter.

Owing to its appeal to the imagination, and to the fear and reverence it has ever aroused, the lion has often been a favourite with symbolists, especially religious symbolists. Our modern anthropologists and folk-lore experts have furnished us with numberless examples of this, even among primitive folk now living, who are sometimes found worshipping the animal. Among the early peoples of India the lion was often used, and generally with the same significance, as standing for "the divine spirit in man." Among the early Egyptians it was still more venerated, as may be learned from their monuments, their temples, and especially their sphinxes; if we may trust

our authorities in the matter, the Nile dwellers used it as a symbol of the life-giving power of the sun and the sun's ability to bring about the resurrection of vegetation in the spring time. In some of the sculpture left by the Egyptians to illustrate the rites of the Egyptian Mysteries the candidate is shown lying on a couch shaped like a lion from which he is being raised from the dead level to a living perpendicular. The bas-reliefs at Denderah make this very plain, though they represent the god Osiris being raised instead of a human candidate. "Here," writes J. E. Harrison in her very interesting little book on "Ancient Art and Ritual," "the God is represented first as a mummy swathed and lying flat on his bier. Bit by bit he is seen raising himself up in a series of gymnastically impossible positions, till he rises . . . all but erect, between the outstretched wings of Isis, while before him a male figure holds the Crux Ansata, the 'cross with a handle,' the Egyptian symbol of life."

The crux ansata was, as Miss Harrison truly says, the symbol of life. Originally a stick, with a cross-piece at the top for a handle, it was used to measure the overflow of the Nile: but inasmuch as it was this overflow that carried fertility into Egypt, the idea of a life-giving power gradually became transferred to the instrument itself, in the same manner that we attribute to a writer's "pen" his ability to use words. A few of our Masonic expositors, among whom Albert Pike may be numbered, have seen in the crux ansata the first form of that Lion's Paw by which the Masonic Horus is raised. If this be the case, the Lion's Paw is a symbol of life-giving power, an interpretation which fits in very well with our own position as outlined in the two preceding sections.

But it is also possible to trace the Lion's Paw symbolism to another source. Among the Jews the lion was sometimes used as the emblem of the Tribe of Judah; as the Messiah was expected to spring from that Tribe the Lion was also made to refer to him, as may be seen in the fifth verse of the fifth chapter of the Book of Revelation, where Jesus Christ is called the "Lion of the Tribe of Judah." It was from this source, doubtless, that the Comacines, the great Cathedral Builders of the Middle Ages, who were always so loyal to the Scriptures, derived their habitual use of the lion in their sculptures. Of this, Leader Scott, the great authority on the Comacines, writes that, "My own observations have led me to the opinion that in Romanesque or Transition architecture, i.e., between A.D. 1000 and 1200, the lion is to be found between the columns and the arch—the arch resting upon it. In Italian Gothic, i.e., from A.D. 1200 to 1500, it is placed beneath the column. In either position its significance is evident. In the first, it points to Christ as the door of the church; in the second, to Christ, the pillar of faith, springing from the tribe of Judah." Since the cathedral builders were in all probability among the ancestors of Freemasons it is possible that the Lion symbolism was inherited from the Comacines.

During the cathedral building period, when symbolism was flowering out on all sides in mediæval life, the lion was one of the most popular figures in the common animal mythology, as may be learned from the Physiologus, the old book in which that mythology has been preserved. According to this record, the people believed that the

whelps of the lioness were born dead and that at the end of three days she would howl above them until they were awakened into life. In this the childlike people saw a symbol of Christ's resurrection after He had lain dead three days in the tomb; from this it naturally resulted that the lion came to be used as a symbol of the Resurrection, and such is the significance of the picture of a lion howling above the whelps, so often found in the old churches and cathedrals.

The early Freemasons, so the records show, read both these meanings,—Christ and Resurrection,—into the symbol as they used it. And when we consider that most of Freemasonry was Christian in belief down at least to the Grand Lodge era, it is reasonable to suppose that the Lion symbol may have been one of the vestiges of that early belief carried over into the modern system. If this be the case the Lion's Paw has the same meaning, whether we interpret it, with Pike, as an Egyptian symbol, or with Leader Scott, as a Christian emblem, since it stands for the life-giving power, a meaning that perfectly accords with its use in the Third Degree. This also brings it into harmony with our interpretation of Eternal Life for in both its Egyptian and its Christian usages it refers to a raising up to life in this world, and not to a raising in the world to come.