Sacred Texts Freemasonry Index Previous Next

Buy this Book on Kindle

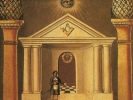

Symbolical Masonry, by H.L. Haywood, [1923], at sacred-texts.com

"In all my research and study, in all my close analysis of the masterpieces of Shakespeare, in my earnest determination to make those plays appear real on the mimetic stage, I have never, and nowhere, met tragedy so real, so sublime, so magnificent as the legend of Hiram. It is substance without shadow—the manifest destiny of life which requires no picture and scarcely a word to make a lasting impression upon all who can understand. To be a Worshipful Master and to throw my whole soul into that work, with the candidate for my audience and the lodge for my stage, would be a greater personal distinction than to receive the plaudits of people in the theatre of the world."

When so accomplished a judge and critic as Edwin Booth could speak like this of the Hiram Abiff tragedy we humbler students may be forgiven for approaching such a theme in awe if not in silence; in truth, I may confess that I should not dare to write a line on the subject were it not absolutely necessary to the scope of these studies. The majesty of the drama is not the only deterrent; its origin and its interpretation have engaged our best scholars for many years but they have not yet reached an agreement; many of them remain as wide apart as the poles nor is there any hope for an early uniformity of opinion. Therefore I shall be compelled to lay out for reviews such varying hypotheses as seem most reasonable, leaving to you, reader, the privilege of forming your own conclusions.

It is generally agreed, however, whatever may be our theory of the origin of the drama, that it was first introduced into the Ritual, in its modern form not more than two hundred years ago. Pike describes it as "a modern invention." Vibert calls it "a comparatively late addition" to the Ritual, and Gould went so far as to fix on 1725 as the most probable date of its introduction into its ceremonies. But while, as I have already said, there is general agreement on this, some scholars, and they not the least considerable, contend that the drama could not have been invented outright in 1725 even if it was amplified or improved, and they believe that the story of the great martyrdom must have existed in some form long before the Eighteenth Century. MacBride believes that "there are traces of the Hiramic Legend in connection with the British Craft Lodges prior to 1717." Newton holds that it was in the possession of the French Compagnonage long before that date and that they "almost certainly learned it from the Freemasons." Even Gould, who is so conservative in his opinions, writes that "the traditions which are gathered round Hiram's name" have "come down to us from ancient times."

Eighteenth century writers usually accepted the legend as having been based on actual history, even in details; from this position the pendulum swung to the opposite position, one writer going so far as to say that "nowhere in history, sacred or profane, in no document, upon no monument, is there a single shred of authentic historical evidence to support the Masonic Legend;" while another affirms that "in spite of diligent search no reference on the

[paragraph continues] Hiramic Legend has hitherto been found in Jewish writings." We are now in process of reaction from this extreme negative position as is proved by Max Montesole's brilliant article published in the Transactions of the Arthur's Lodge (vol. i, p. 28) in which he shows that the name of Hiram Abiff in Hebrew literally means "Hiram, his father" or "Hiram, his master," and that the term as such is found in II Chronicles 4: 16. This means that the record tells first of Hiram of Tyre, Solomon's architect, and then of a second Hiram, the former's son or pupil which leaves us to infer that the first Hiram may have died or have been killed.

That this latter supposition is not a modern one is proved by a sentence in one of the oldest Jewish writings in which we read that "all workmen were killed that they should not build another Temple devoted to idolatry, Hiram himself being translated to heaven like Enoch." This is doubtless only a Rabbinic legend but it proves that, even to the Jews of ancient times, there had descended a tradition of the Grand Master's death.

Other writers, however, have not agreed with this historical theory but prefer to believe that the drama was devised during Mediæval times. If so it must have come into existence some time before the fourteenth century, for Speth asserts that there are references to it (veiled) in certain of the Old Charges, and Dr. Marks, a learned Hebrew scholar, declares that he found an Arabic manuscript of that date which contains the sentence, "We have found our Lord Hiram."

Some scholars have argued that the drama was brought to Europe by the Knight Templar. Others have seen in it a literary result of popular interest in the Temple

which was so frequently the theme of books and speeches in seventeenth century England; but a diligent search among this literature has failed to unearth a single reference to Hiram Abiff. (A.Q.C., vol. xii, p. 142.) Nor has an equally diligent search been able to discover any such references in the Mystery Plays which were once so common in Europe, though some scholars have hoped for light from that quarter. (A.Q.C., vol. xiv, p. 60.) Speth considered that the legend may have originated among early builders as a parabolical story suggested by the old customs of sacrificing a human being under the cornerstone of a building. Pike was of the opinion that it was invented by seventeenth century occultists for the purpose of concealing their teachings. Carr traces it back to a legend still found in Operative Lodges while others hold that it was made out of the whole cloth by Anderson or Desaguliers, while others have seen in it a kind of political allegory devised by Oliver Cromwell (of all men!) or some other republican as a blast against royalty.

To me it seems reasonable to believe that the core of the drama came down from Solomon's day; that it was preserved until mediæval times by Jewish, and especially Kabbalistic, literature; that it found a place among the traditions of the old builders because it was so intimately related to the story of the Temple, around which so much of their symbolism revolved; that it was inherited by seventeenth century Masons, in crude form, and along with the mass of other traditions; that it was elaborated and given its literary form by the early framers of the Ritual; and that it was adopted by them because it embodied so wonderfully the idea at the centre of the Third Degree. As I said above, this theory can not be proved by documentary evidence, but it is the opinion toward which the drift of all our data seems to lead one.

The confusion which may have been occasioned by this review of the theories of origin will not be lessened, I fear, when we turn to interpretation, for in this also we find a multitude of counsellors, and few agreeing. To make this diversity as plain as possible I shall set down a table of the theories, with their authors’ names in parentheses, when known; there are fourteen of them (I borrowed the list from Brother Hextall), but even more could be added by a little search.

2. Legend of Isis and Osiris. (Oliver.)

3. Allegory of setting sun. (Oliver.)

4. Death of Abel at hand of Cain.

5. Expulsion of Adam from Paradise. (Oliver.)

6. Entry of Noah into Ark. (Freemason's Magazine.)

7. Mourning of Joseph for Jacob. (Oliver.)

8. An astronomical problem. (Yarker.)

9. Death and Resurrection of Jesus. (Oliver; also Pike, in part.)

10. Violent death of King Charles I. (Oliver.)

11. Persecution of the Templars. (De Quincey.)

12. Political invention by Cromwell. (Oliver.)

13. A parable of old age and death. (Oliver.)

14. A drama of regeneration. (Hutchinson.)

It is highly significant that the majority of these theories were born in Bro. Oliver's learned brain; he devoted a life-time almost exclusively to the study of Masonry, and he was a man of unusual intellect. Yet see how bewildered he became in the presence of the drama! how impotent he was to discover any one fact or event

to which it might refer! Is not this in itself a solution of the problem? For why should we persist in thinking that the legend as we now have it derives its meaning from any event whatsoever? Why may we not believe that it is simply a dramatic parable of a great experience of the soul in its struggle against adversaries, in its apparent defeat, and its ultimate moral victory? Whatever it may have originally meant, this, surely must be its meaning now.

Hiram Abiff is the type of every Christ-like man who lives as an apostle of light and liberty, and his experiences as set forth in the drama are just those experiences, in one degree or another, which attend every such man who stands true to his principles. Adversaries, whether men or circumstances, seek to undermine his courage and betray his soul; they may even encompass his death and apparent defeat, but he lives while they die, for the man who stands true to his loyalties, whatsoever betide, has that within him which contumacy cannot kill, nor death destroy. Such a man is inconquerable even in mortality, and on his lips we might place, without any incongruity whatsoever, the magnificent exclamation of the heroic Fichte:

"I raise my hand to the threatening rock, the raging flood, and the fiery tempest, and cry, 'I am eternal and defy your might; break all upon me; and thou Earth, and thou Heaven, mingle in the wild tumult; and all ye elements, foam and fret yourselves, and crush in your conflict the last atom of the body I call mine,' my WILL, in its own firm purpose, shall soar unwavering and hold over the wreck of the universe!"