Sacred Texts Legendary Creatures Symbolism Index Previous Next

Buy this Book at Amazon.com

Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art, by John Vinycomb, [1909], at sacred-texts.com

"Feasts that Thessalian centaurs never knew."

Thomson, "Autumn."

Under these names is blazoned a fabled monster of classic origin, half man, half horse, holding an arrow upon a bended bow. It is one of the twelve signs of the Zodiac, commonly called Sagittarius, otherwise Arcitenens, and marked by the hieroglyph ♐. In its signification in arms it may properly be applied to those who are eminent in the field.

The arms traditionally assigned to King Stephen

are thus described by Nicholas Upton: "Scutum rubeum, in quo habuit trium leonum peditantium corpora, usque ad collum cum corporibus humanis superius, aa modum signi Sagittarii, de auro," In this, as in some

other early examples, it is represented as half man, half lion.

The arms of Stephen are sometimes represented with but one sagittary, and is said to have been assumed by him in consequence of his having commenced his reign under the sign of Sagittarius. Others say because he gained a battle by the aid of his archers on entering the kingdom. Others, again,

say that the City of Blois used the ensign of a sagittary as an emblem of the chase; and Stephen, son of the Compte de Blois, assumed that ensign in his contest with the Empress Maude or Matilda. There is no contemporary authority, however, it must be confessed, for any of these derivations. A sagittary is seen upon the seal of William de Mandeville (temp. Henry III.), but not as an heraldic bearing.

The crest of Lambart, Earl of Cavan, is: On a mount vert, a centaur proper, drawing his bow gules, arrow or. It also appears as the crest of Askelom, Bendlowes, Cromie, Cruell, Lambert, Petty, Petty-Fitzmaurice.

The term Centaur is most probably derived from the words κεντέω (to hunt, or to pursue) and ταῦρος (a bull), the Thracians and Thessalians having been celebrated from the earliest times for their skill and daring in hunting wild bulls, which they pursued mounted on the noble horses of those districts, which were a celebrated breed even in the later times of the Roman Empire. A centaur carrying a female appears on a coin of Lete, which, according to Pliny and Ptolemy, was situated on the confines of Macedonia, and the fables of the centaurs, &c., in that and neighbouring districts abounding in a noble breed of horses, arose no doubt from the feats performed by those who first subjugated the horse to the will of man, and who mounted on one of these beautiful animals and guiding it at will, to approach or retreat

with surprising rapidity, gave rise in the minds of the vulgar to the idea that the man and the horse were one being.

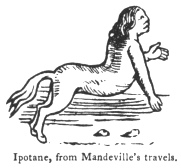

Sir John de Mandeville in his travels (printed by Wynken de Worde, 1499), tells us that in Bacharie

|

We have in modern history a singular and interesting example of a similar superstition. When the natives of South America—where the horse was unknown—first saw their invaders, the Spaniards, mounted on these animals and in complete armour, they imagined that the cavalier and steed formed but one being of supernatural powers and endowments.

Such groups as those exhibited on the rude money of Lete and other places were doubtless the first steps toward the treatment of similar subjects by Phidias, the celebrated Greek sculptor, whose works illustrating the battle of the Lapithæ and the Centaurs adorned the metopes of the Parthenon at Athens, to which they also bear a striking affinity in the simplicity of their conception.

A curious example of the compounded human and

animal forms similar to the sagittary is represented upon a necklace found in the Isle of Rhodes, and now in the Musée Cluny, Paris. It is formed of a series of thin gold plates whereon is represented in relief the complete human figure conjoined to the hinder part of a stag (or horse). This is alternated

with another compound figure, human and bird, holding up two animals by the tails, both subjects, each in their own way, suggestive of the fleet and dexterous hunter.

In Homer's account the centaurs are obviously no monsters, but an old Thessalian mountain tribe, of great strength and savage ferocity. They are merely said to have inhabited the mountain districts of Thessaly, and to have been driven thence by the

[paragraph continues] Lapithæ into the higher mountains of Pindus. Their contest with the Lapithæ is generally conceived as a symbol of the struggle of Greek civilisation with the still existing barbarism of the Early Pelasgian period. This may be the reason why Greek art in its prime directed itself so especially to this subject.

The origin of this contest is referred to the marriage feast of Pirithous and Hippodamia, to which the principal centaurs were invited. The centaur Eurytion, heated with wine, attempted to carry off the bride. This gave rise to a struggle for supremacy which, after dreadful losses on both sides, ended in the complete defeat of the centaurs, who were driven out of the country. The custom of depicting the centaurs as half man, half horse arose in later times,

and became a favourite subject of the Greek poets and artists.

Amongst the centaurs, Chiron, who was famous alike for his wisdom and his knowledge of medicine, deserves mention as the preceptor of many of the heroes of antiquity. Homer, who knew nothing of the equine shape of the centaurs, represents him as the most upright of the centaurs, makes him the friend of Achilles, whom he instructed in music, medicine and hunting. He was also the friend of Heracles, who, by an unlucky accident, wounded him with a poisoned arrow. The wound being incurable, he voluntarily chose to die in the place of Prometheus. Jupiter placed him among the stars, where he is called Sagittarius.

Bucentaur, from Greek βοῦς (bous) an ox, and κένταυρος (kentauros) a centaur, was, in classic mythology, a monster of double shape, half man, half ox. The state barge of the Doge of Venice was so termed.

The Minotaur slain by Theseus had the body of a man and the head of a bull.