Thirty Minor Upanishads, tr. by K. Narayanasvami Aiyar, [1914], at sacred-texts.com

ॐ

FOREWORD

FOR the first time it is, I believe, that the English translation of so many as 30 Upanishaḍs is being put forth before the public in a collected form. Among the Hinḍū Scriptures, the Veḍas hold the pre-eminent place. The Upanishaḍs which are culled from the Āraṇyaka-portions of the Veḍas—so-called because they were read in the Araṇya (forest) after the learner had given up the life of the world—are regarded as the Veḍānṭa, or the end or final crown of the Veḍas. Veḍānṭa is also the end of all knowledge, since the word Veḍas means according to its derivation 'knowledge'. Rightly were the Upanishaḍs so considered, since their knowledge led a person to Āṭmā, the goal of life. The other portion of the Veḍas, viz., Samhiṭas and Brāhmaṇas, conferred upon a man, if he should conform to the requisite conditions, the mastery of the Universe only which is certainly inferior to Āṭmā. It is these Upanishaḍs that to the western philosopher Schopenhauer were the "solace of life".

There are now extant, in all, 108 Upanishaḍs, of which the principal or major 12 Upanishaḍs commented upon by Śri Śaṅkarāchārya and others were translated into English by Dr. Roer and Rāja Rājenḍra Lāl Miṭra and re-translated by Max Muller in his "Sacred Books of the East," together with one other Upanishaḍ called Maiṭrāyaṇī. Of the rest, 95 in number, two or three Upanishaḍs have appeared in English up to now, but never so many as are here presented to the public, so far as I am aware.

Many years ago, the late Sunḍara Śastri, a good Sanscrit Scholar and myself worked together to put into English garb the Upanishaḍs that had not been attempted before, and

succeeded in publishing most of those which are here gathered in the monthly issues of The Theosophist. The Karmic agents willed that my late co-worker should abandon his physical garment at a premature age. Then I resolved upon throwing up my worldly business of pleading the cause of clients before the bench for that of pleading the cause of God before the public. The incessant travel in that cause since then for over 18 years from place to place in all parts of India left me no leisure until now to republish all the above translations in a book form. But when this year a little rest was afforded me, I was able to revise them as well as add a few more. I am conscious of the many faults from which this book suffers and have no other hope in it than that it will serve as a piece of pioneer work, which may induce real Yogins and scholars to come into the field and bring out a better translation.

There are many editions of the Upanishaḍs to be found in Calcutta, Bombay, Poona, South India and other places. But we found that the South Indian editions, which were nearly the same in Telugu or Granṭha characters, were in many cases fuller and more intelligible and significant. Hence we adopted for our translation South Indian editions. The edition of the 108 Upanishaḍs which the late Tukaram Tatya of Bombay has published in Ḍevanāgari characters approaches the South Indian edition. As the South Indian edition of the Upanishaḍs is not available for the study of all, I intend to have the recensions of that edition printed in Ḍevanāgari characters, so that even those that have a little knowledge of Sanscrit may be able to follow the original with the help of this translation.

Transliteration

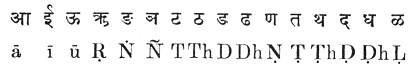

In the transliteration of Sanscrit letters into the English alphabet certain difficulties present themselves. Let me take first the letter #. There are three letters in Sanscrit #, #, and #. They are differently pronounced and one should not be confounded with another. For the first letter we have the English equivalent S and for the last Sh. But for the second one we

have none whatsoever. The prominent writers in the field of Theosophy have been transliterating this letter into Sh. Hence in writing the word ### they made it Kāshi in the English language. They utter it also in the same manner. To a South Indian ear, it is rather grating. The manṭras especially depend for their efficacy upon proper pronunciation. When we therefore utter the words wrongly, there is committed according to Sanscrit writers, Varṇa-Haṭyā-Ḍosha or the sin of the murder of letters or words. In my translation I have represented the letter # by Ś and not by Sh, since I consider the latter to be a mistake. Other transliterations are:—

It would be well if our leaders of thought conferred together and came to some agreement upon the question of transliteration.

The Order of the Upanishaḍs

The Upanishaḍs translated have been classified under the headings of (1) Veḍānṭa, (2) Physiology, (3) Manṭra, (4) Sannyāsa and (5) Yoga. But these are not hard and fast divisions. For instance in the Sannyāsa and Yoga Upanishaḍs, manṭras also are given. But in the Manṭric Upanishaḍs, Manṭras alone are given.

Veḍānṭa and Yoga Upanishaḍs

The Upanishaḍs that come under the headings of Veḍānṭa and Yoga are the most important. But it is the latter Upanishaḍs that are most occult in their character, since it is they that give clues to the mysterious forces located in nature and man, as well as to the ways by which they maybe conquered. With reference to Veḍānṭa, the ancient teachers thereof have rightly ordained that none has the right to enter upon a study of it, unless he has mastered to a slight degree at least the Sāḍhana-Chaṭushtaya, or four means of salvation. He should not, only be convinced in theory of the fact that Āṭmā

is the only Reality, and all else are but the ephemeral things of the world, but he should also have outgrown in practice the craving for such transitory worldly things: besides he should have developed a fair mastery over the body and the mind. A non-compliance with these precedent conditions leads men into many anomalies. The orthodox and the clever without any practice are placed in a bad predicament through a study of these Upanishaḍs. In such Upanishaḍs as Maiṭreya and others, pilgrimages to holy places, the rituals of the Hinḍūs, ceremonial impurities at the time of birth and death, Manṭras, etc., are made light of. To the orthodox that are blind and strict observers of rites and ceremonies, statements like these give a rude shock. Hence Upanishaḍs are not meant for persons of this stamp. Nor are they intended tor mere intellectual people who have no knowledge of practice about them, and are immersed in the things of the world. Some of us are aware of the manner in which men with brains alone have made a travesty of the doctrine of Māyā. Not a few clever but unprincipled persons actually endeavour to justify arguments of all kinds of dissipations and wrong conduct by the assertion that it is all Māyā. The old Ṛshis were fully aware of the fact that Veḍānṭa would be desecrated by those that had not complied with its precedent conditions. Only when the desires and the self are overcome and the heart is made pure, or as Upanishaḍic writers put it, the heart-knot is broken, only then the Āṭmā in the heart will be truly realised: and then it is that the Āṭmā in all universe is realised also, the universe being then seen as Māyā. But so long as the Āṭmā in the heart is not realised through living the life, the universe will not be realised as Māyā, and "God everywhere" will be but in words.

One special point worthy of notice in the Upanishaḍs is that all the knowledge bearing upon a subject is not put forward in one and the same place. We have to wade through a mass of materials and a number of Upanishaḍs, ere we can have a connected view of a subject. In modern days when 'a subject is taken up, all the available information is given in one place in a systematic manner. But not so in the Upanishaḍs.

[paragraph continues] Take the subject of Prāṇas which refer to life itself. In one Upanishaḍ, one piece of information is given, another in another and so on. And unless we read them all together and reconcile the seemingly discrepant statements, we cannot have a complete and clear knowledge of the subject. This process was adopted by the Ṛshis, probably because they wanted to draw out thereby the intellectual and spiritual faculties latent in the disciple, and not to make him a mere automaton. In these days when knowledge is presented in a well-assimilated form, it is no doubt taken up easily but it does not evoke the latent reasoning power so much. When therefore the disciple went in the ancient days to the teacher for the solution of a difficulty, having been unable to find it himself after hard thinking, it was understood easily and permanently because of the previous preparation of the mind, and was also reverently appreciated as a boon and godsend, because of the difficulty previously experienced. The function of the teacher was not only to explain the difficult points to the taught, but also to make him realise those things of which understanding was sought. As an illustration, we might take the case of the soul. The Guru not only explained the difficult passages or points relating to the soul, but also made the disciple leave the body or bodies and realise himself as the soul. As we cannot get such Gurus in the outer world nowadays, the only thing left to do instead is to secure the publication of simple treatises on matters of Veḍānṭa and Yoga for the benefit of the public. I hope, I shall before long be able to make a start in this direction.

In studying the Upanishaḍs on Veḍānṭa and Yoga, we find certain peculiarities which throw a light on their greatness. Both of them lay stress upon certain centres in the human body for development. The 12 major Upanishaḍs as well as the Veḍānṭa Upanishaḍs herein published deal with the heart and the heart alone; while the Yoga Upanishaḍs treat of many centres including the heart. For the purpose of simplification, all the centres may be divided under the main headings of head, heart and the portion of the body from the navel downwards.

But why? The key which will unlock these secrets seems to be this. All religions postulate that the real man is the soul, and that the soul has to reach God. Christianity states that God created the soul in His own image and that the soul has to rise to the full stature of God in order to reach Him. Hinduism says that Jīvāṭmā (the human soul) is an Amśa or portion of Paramāṭmā, or God, which is to eventually unfold the powers of God, and compares it with a ray of the sun of God, or a spark out of the fire of God. In all religions, there is an unanimity of opinion that the soul is a likeness of God, having God's powers in latency to be unfolded hereafter. Let us therefore first understand the attributes of God. He is said to have omnipresence, omniscience and omnipotence. Hinḍūism translates these ideas into Saṭ, Chiṭ and Ānanḍa. They are eternal existence, infinite knowledge, and unlimited power. The soul identifying itself with the body thinks it lives for the life-term of the body only; cooped up by the brain, it imagines, it has only the knowledge circumscribed by the brain; carried away by the pleasures of the senses, it whirls about in the midst of them as if they constituted the Real Bliss. But when it wakes up from the dream of the lower things of the body and glances upwards to the higher world of Spirit, it discovers its delusions and finds itself to be of the same nature as the God above, who is eternal, all-knowing and all-powerful. And this discovery has to be made by each soul in the human body, in which it is functioning, through the three main centres of head, heart and navel. Through the heart, it cuts the heart-knot and realises its all-pervading character when it realises its eternity of existence; through the brain, it rises beyond it through its highest seat, viz., Sahasrāra which corresponds to the pineal gland in the physical body, and obtains its omniscience; through the navel, according to the Upanishaḍs—it obtains a mastery over that mysterious force called Kuṇdalinī which is located therein, and which confers upon it an unlimited power—that force being mastered only when a man arises above Kāma or passion. Psychologists tell us that desires when conquered lead to the development of will. When will is developed to a great degree,

naturally great power, or omnipotence, ensues: our statement is that Kuṇdalinī when conquered leads to unlimited powers and perfections, or Siḍḍhis like Aṇimā, etc., and that Kuṇdalinī can only be conquered through rising above the desires of the senses.

From the foregoing it is clear that the Veḍānṭa Upanishaḍs are intended only for those devotees of God that want to have a development of the heart mainly, and not of the brain and the navel, and that the Yogic Upanishaḍs are intended for those that want to have an all-round development of the soul in its three aspects. Here I may remark that Śri Śaṅkarāchārya and other commentators commented upon the 12 Upanishaḍs only, since other Upanishaḍs treating of Kuṇdalinī, etc., are of an occult character and not meant for all, but only for the select few who are fit for private initiation. If they had proceeded to comment upon the minor Upanishaḍs also, they would have had to disclose certain secrets which confer powers and which are not meant, therefore, for all. It would be nothing but fatal to the community, were the secrets leading to the acquisition of such powers imparted indiscriminately to all. In the case of dynamite, the criminal using it may be traced, since it is of a physical nature, but in the case of the use of the higher powers, they are set in motion through the will, and can never be traced through ordinary means. Therefore in the Upanishaḍ called Yoga-Kuṇdalinī, the final truths that lead to the realisation of the higher powers are said to be imparted by the Guru alone to the disciple who has proved himself worthy after a series of births and trials.

In order to expound the Upanishaḍs, especially those that bear upon Yoga, some one who is a specialist in Yoga—better still, if he is an Adept—should undertake the task of editing and translating them. The passages in Yoga Upanishaḍs are very mystic sometimes; sometimes there is no nominative or verb, and we have to fill up the ellipses as best as we can.

One more remark may be made with reference to the Upanishaḍs. Each Upanishaḍ is said to belong to one of the Veḍas. Even if we take the 12 Upanishaḍs edited by Max Muller and others, we find some of them are to be found in the existing

[paragraph continues] Veḍas and others not. Why is this? In my opinion this but corroborates the statement made by the Vishṇu-Purāṇa about the Veḍas. It says that at the end of each Ḍwāpara Yuga, a Veḍa-Vyāsa, or compiler of the Veḍas, incarnates as an Avaṭāra of Vishṇu—a minor one—to compile the Veḍas. In the Yugas preceding the Kali Yuga we are in, the Veḍas were "one" alone though voluminous. Just before this Kali Yuga began, Kṛshṇa-Ḍwaipāyana Veḍa-Vyāsa incarnated, and, after withdrawing the Veḍas that were not fit for this Yoga and the short-lived people therein, made with the aid of his disciples a division of the remaining portions into four. Hence perhaps we are unable to trace the Veḍas of which some of the extant Upanishaḍs form part.

K. Narayanaswami

Adyar, March 1914.