Sacred Texts

Australia

Images

Index

Previous

Next

CHAPTER III

INITIATION CEREMONIES

Division of tribes into three groups according to the nature of the initiation ceremony. Group 1, tribes with neither circumcision nor subincision. Group 2, tribes with circumcision only. Group 3, tribes with circumcision and subincision.--List of the tribes.--Initiation on Melville Island.--Yam ceremony.--Status terms of youths and girls taking part.--Preparing the ceremonial ground.--Making a special fire to roast the yams.--Performance of ceremonies and painting of the performers.--Ducking the initiate in a water pool.--Pulling out of hair.--Special decorations worn by boys and girls passing through the ceremony and by the mother of the boy.--Port Essington tribe.--First ceremony or Nailpur; second ceremony or Wokunjari.--Kakadu tribe.--First ceremony or Jamba.--Showing the initiate the Jamba. Food restrictions.--Kangaroo ceremony.--Putting belts and armlets on the initiate.--Removing food restrictions.--Second ceremony or Ober.--Youths sent out to distant camps to invite strangers.--Special Tjaina ground.--Kangaroo and Snake ceremonies.--Third ceremony or Jungoan.--Fourth ceremony or Kulori, associated with a yam.--"Singing" different articles of food and so removing the restrictions.--Fifth ceremony or Muraian.--Performance of ceremonies.--Sacred objects associated with the Muraian.--Larakia tribe.--Belier ceremony.--Showing the Bidu-bidu or bull-roarer.--Mullinyu ceremony.--Worgait tribe.--Kundein ceremony.--Circumcision.--Baquett ceremony.--Showing the bull-roarer.--Djauan tribe.--Mindirinni ceremony.--Circumcision.--Showing the Kunapippi or bull-roarer.--Mungai ceremony.--Mungarai tribe.--Kalal camp and showing sacred

{p. 89}

ceremonies and the Kunapippi or bull-roarer.--Circumcision.--Wandella status.--Subincision.--Nadiriga status.--Smoking the nadiriga.--Nullakun tribe.--Kokullal camp at which ceremonies are performed.--Special stick called Jappa round which the lubras dance.--Circumcision.--Showing the Kunapippi or bull-roarer.

So far as initiation is concerned these northern tribes be divided into three main groups that are clearly marked off from one another by the presence or absence of certain characteristic ceremonies. In all tribes hitherto described by us, in Central and Northern Central Australia, the two ceremonies of circumcision and subincision are carried out, but as the northern coast is approached we meet with tribes which first of all drop, if they have ever practised, the rite of subincision, and, lastly, in the very north and on the Islands, we meet tribes that perform neither of these ceremonies. In no case is the knocking out of a tooth in any way connected with initiation. The three groups are as follows:--(1) Those in which neither circumcision nor subincision is practised. This includes a number of tribes inhabiting Bathurst and Melville Islands, the Coburg Peninsula and the country drained by the East, South and West Alligator Rivers and, probably, also a large extent of country to the east of this along the coast line. Amongst these tribes are included the following:--Melville and Bathurst Island Tribes, Iwaidji, Kakadu, Koarnbut, Norweilemil, Punuurlu, Kumertuo, Geimbio, Noalanji and Larakia.

(2) Those in which circumcision only is practised. This includes a smaller number inhabiting, mainly, country to the south of that of the first group of tribes, though, in the case of the Worgait, they extend to the north-west coast. They are the Worgait, Warrai, Djauan and Nullakun.

{p. 90}

(3) Those in which both circumcision and subincision are practised. They inhabit the upland country, inland from the coastal ranges and extend, on the one hand, right to the centre of the continent, and, on the other hand, eastwards to the Gulf of Carpentaria.[1] There is no doubt, also, but that they pass right across into Western Australia. Amongst them are included the following:--Mungarai, Yungman, Mudburra, Waduman, Ngainman, Bulinara, Tjingilli, Mara, Binbinga, etc.

In the following list the names of the more important tribes of the Northern Territory are given, so far as they are known at present. They are divided into three groups, according to the nature of their initiation ceremonies.[2]

GROUP 1.--Neither Circumcision nor Subincision.

|

1. Melville Island. |

20. Punuurlu. |

|

2. Bathurst Island. |

22. Kumertuo. |

|

21. Iwaidji. |

15. Kulunglutji. |

|

14. Kakadu. |

17. Geimbio. |

|

18. Koarnbut. |

44. Noalanji. |

|

43. Norweilemil (or Lemil). |

16. Umoriu. |

|

|

13. Larakia. |

|

|

19. Watta. |

GROUP 2.--Circumcision only.

|

3. Worgait. |

6. Mulluk-Mulluk (?). |

|

5. Wulwullam. |

7. Brinken |

|

23. Djauan. |

|

|

26. Nullakun. |

|

|

4. Warrai. |

|

[1. We have dealt with several of these tribes in Native Tribes of Central Australia, p. 212, and Northern Tribes of Central Australia, p. 328.

2. The approximate distribution of these tribes is shown in map A. The number opposite each tribe corresponds to the number on the map. Tribes numbered 1-41 are referred to in this volume.]

{p. 91}

GROUP 3.--Circumcision and Subincision.

|

45. Dieri. |

33. Kallawa. |

|

46. Urabunna. |

52. Anula. |

|

47. Wonkgongaru. |

35. Karawa. |

|

41. Arunta. |

53. Wilingura. |

|

48. Luritja. |

37. Allowiri. |

|

40. Unmatjera. |

54. Yarrowin. |

|

39. Kaitish. |

32. Gnuin. |

|

38. Warramunga. |

28. Yukul. |

|

42. Walpari. |

27. Mara. |

|

49. Bingongina. |

24. Mungarai. |

|

34. Tjingilli. |

25. Yungman. |

|

30. Umbaia. |

8. Mudburra. |

|

31. Nganji. |

9. Waduman. |

|

36. Worgai. |

55. Ngainman. |

|

50. Kudenji. |

10. Billianera. |

|

29. Binbinga. |

11. Airiman. |

|

51. Wanji. |

56. Kadjerong. |

|

|

12. Allura. |

The natives on Melville and Bathurst Islands differ very much in regard to their ceremonies and customs, from the typical tribes of the mainland, and in nothing is this more clearly seen than in the ceremonies attendant upon the admission of their young men to the status of manhood. It is quite possible that there are certain ceremonies of a very special nature in addition to those now described, but a very striking feature of, at all events, some of the more important of them is that all the members of the tribe--men, women and children--take part in them. This is quite opposed, and stands in strong contrast, to the customs of most mainland tribes, amongst whom women and children, except to a very limited extent, are rigidly excluded from all active participation in them, and, as a rule, are not even allowed to come anywhere near the ceremonial ground. So far as I have been able to discover there is no such thing as a churinga or bull-roarer used. The natives assured me that they had no such thing, and when I showed the old men one and showed them also illustrations of Arunta and other natives using it, though apparently they were keenly

{p. 92}

interested in it and anxious to know all that I could tell them about these tribes, they still professed complete ignorance of any such thing amongst themselves, although certain of them knew that it was used in the Larakia tribe on the mainland. I therefore think it very probable that the Melville and Bathurst Island natives have no such thing as a churinga, and in saying this I am influenced by the knowledge that, so far as I could discover, no churinga or bull-roarer is known amongst the group of tribes inhabiting the Coburg Peninsula and I the large area drained by the Alligator Rivers, these tribes being the nearest neighbours of the Melville Islanders. It is, however, very difficult to make any definite statement in regard to matters such as this. It was only last year, though the Larakia tribe had been known to white men for forty years at least, that I was able to find out that, during their initiation ceremonies, they used a churinga. Future investigations may perhaps discover either a churinga, or something equivalent to it, amongst the natives of Melville and Bathurst Islands.

An equally striking feature of the ceremonies is the entire absence of any mutilation of the body. Neither circumcision nor subincision is practised, and as the men, under normal conditions, are stark naked, the fact is very evident. They have a most curious habit when standing still of pressing the penis back between the legs so that the tip of the prepuce can be seen from behind.

The initiation of young men on Melville Island is intimately associated with what is known as a Yam ceremony. This special form of yam, which is eaten, but does not form such an important article of food as certain other yams, is called Kolamma, though it is sometimes pronounced as if it were spelt Kulemma, the "k" also being often hardly sounded. It is covered with a number of

{p. 93}

little roots which look like very strong hairs. These are called itjimma, the same name being applied to the hair on the arms and legs. Whiskers are called dunimma.

The central figure in the ceremony was a boy, who appeared to be not more than fourteen or fifteen years old. He was the initiate and was called Watjinyerti--a special status term applied to boys at this particular stage. There was also an older youth who had figured as Watjinyerti at the last initiation ceremony a year ago and was now called Mikinyerti. In addition, there were two younger boys who will attain the status of Watjinyerti at the next ceremony. They were called Marukumana. A very striking feature was the fact that certain young girls took a very definite part in the performance. One of them, who was not more than ten or eleven years old, was called Mikinyertinga. She seemed to correspond, amongst the girls, to the Watjinyerti amongst the boys, and, twice at least during the performance, was specially decorated and much in evidence. In addition to her there were three other girls, the equivalents of the Marukumana amongst the boys, who were called Mikijeruma, and, like the Marukumana boys, were passing through the ceremony for the first time. On this occasion the Mikinyerti was the mother's brother of the Mikinyertinga girl, and, consequently, much older than she was, in fact, he was really one of the younger amongst the initiated men, but in these tribes the progress of full initiation is a lengthy one. Her father decided that she should go through because of the fact that her mother's brother was doing so.

On the day on which the ceremony began, the men collected together early in the morning, about eight o'clock, and, after much singing and yelling at the top of their voices, they went out into the bush to collect yams. They were accompanied by the Mikinyerti, but

{p. 94}

not by the Watjinyerti, who had to go to the mangrove swamp to put mud over himself. If he did not do this sores might break out all over him. Four young girls and two older ones also went out with the men, while the Marukumana remained in camp.

The morning was spent gathering the yams, which were then placed in two pitchis and immersed in a waterhole about a mile away from the main camp. When this was over the men came into the latter and decorated themselves with pipe clay and whitened bird's down. The majority of them had the down plastered over their chests, shoulders, and upper parts of their arms and backs and a line of white running down the middle of the abdomen (Fig. 29). Everyone had half of the forearm and the hand whitened and a broad band across the face. In most cases this included the whole forehead and as far down as the level of the moustache, but one or two of the older men, and amongst them the leaders of the ceremony, had only a circle round each eye and a band across the nose. All of them had their hair whitened, and perhaps the most extraordinary feature was the treatment of the beard. These men have very much better beards than many, in fact most, of the northern mainland tribes. During the first part of this yam ceremony they draw the sap of a tree known as milk wood (Alstonia sp.). When a cut is made in the bark of this tree a whitish liquid exudes which becomes sticky. The natives smear this over their beards so that the hairs stand out stiffly in a kind of fringe or ruff round the face. The leader, who had no moustache or hairs on his cheeks or lower lip--he had pulled them all out--was especially noticeable. He looked very much like a white-haired, glorified orang-utan. A few of the men, including the leader, contented themselves with drawing

{p. 95}

only lines of pipe clay on their bodies, arms, and legs. It was dull, gloomy, and raining hard at intervals and the painting and singing went on till nearly three o'clock the afternoon. When all was ready, the men, amongst whom was the Mikinyerti, left the main camp, where they had been singing and decorating themselves. They came on to the site chosen for the ceremonial ground, brandishing their yam sticks, called alluguni, and yelling Ya bai e e! Ya bai e e!

When the women, who were some little distance away in the scrub, and with whom were the three Marukumana boys and the Watjinyerti, heard this yelling, some of them came up to watch what was being done, but the boys remained in the scrub. Two of the women, one of whom was the mother of a Marukumana boy and the other the father's sister of a Mikijeruma girl, had their hair curiously decorated. By means of bees' wax it was all made up into little balls, the size of a large pea, and each of them was coated with yellow ochre, producing a most curious effect.

The men stood for a short time, bunched together and yelling loudly, with their yam sticks waving above their heads. Then they suddenly stooped down, plucked up tufts of grass by the roots and threw them about in all directions, shouting out as they did so, Brr! Brr! which is a cry indicating both defiance and the fact that, in any contest, the men making it are winning. Then they all set to work, vigorously, with their yam sticks, and, in a very short time, they had the ground cleared of grass and shrubs and had also piled up earth in a ring enclosing it, the cleared space measuring about twenty feet in diameter. The four young Mikijeruma girls, already referred to, ran on to the ground and joined the men when first they, came up, watched them for a short time,

{p. 96}

and then ran back to the women. In a very short time there was quite an encampment of roughly made bark mia-mias around the ground and no attempt of any kind was made to secure privacy. The only thing was that no women or children, except in the instance above-mentioned, and on one other occasion, were allowed to cross the ring. Otherwise, everything was done in public and the whole scene, with the decorated men and women, wandering about the little bark huts, each with its own fire, from which the blue smoke curled up among the forest trees and cycads, was most picturesque. Unfortunately, it rained hard, but this made not the slightest difference to anyone. When a particularly heavy shower came on, they either went under their mia-mias or protected themselves with a sheet of stringy-bark, bent double. At this time of the year the bark can be easily stripped from the tree and is used for many purposes, either for a house, a boat, a basket, or an umbrella. The Mikinyerti was with the men, the Watjinyerti was in the scrub, under the charge of his future wife's brother, and the three Marukumana boys had been sent away into the bush by the old men, with instructions as to what they were to do.

When the ground was cleared there was a short pause and then an old man--it did not apparently matter who--rose to his feet and began to walk round and round, knocking two sticks together (Fig. 30). While doing this, everyone adopts the same characteristic attitude. The man holds his left arm above his head so that his hand, in which he has a stick, is behind the level of his head. He strikes the stick with another in his right hand, singing as he does so. This special stick is called anadaunga. Men often walk round without a stick and then they always hold the left arm in front of the head,

{p. 97}

touching the forehead with the forearm so as to shield the eyes.

The first performer opened the ceremony by singing of the salt water, then another began and sang about Cooper and his house, saying that Jokuppa was tall but he was not nearly as tall as his house.[1] Finally all the men were singing of rain, sea, boats, trees, grass, and, in fact, of everything that they could think of. Often a man would come to the end of one "song" and while thinking, of something else to sing, he always kept up a cry of Ha-ha-ha-er-er-er-, the former on a higher and the latter on a lower note.

This "singing" everything is a very characteristic feature of the Melville and Bathurst Islanders, as is also their custom, while ceremonies are being performed, of bending the body forwards and at the same time striking the buttocks with open hands and stamping furiously on the ground. Apart, also, from these ceremonies this curious repetition of names is frequently met with. Cooper and myself were once travelling in a dug-out canoe with four natives, and, as we were going along the coast, they spent most of the time naming things. One boy would say "mangrove," another "the leaves of the mangrove," another would say "dugong," and another "the head of the dugong," and so on, in endless succession. It sounded just as if they were vying with one another to see who could mention the most names, and all the time they were laughing gaily and evidently enjoying themselves.

After the singing had gone on for about half an hour

[1. This refers to Mr. R. J. Cooper, a noted Buffalo hunter, who is practically King of Melville Island, where he has great influence amongst the wild natives. He is popularly known as Joe Cooper, a name which the natives have transformed into Jokuppa.]

{p. 98}

the Watjinyerti, whose face was all painted black, was brought in from the scrub by his guardian and taken to his father. The latter led him to an old yauaminni, (mother's elder brother's son) who decorated him with, armlets called bannajinni. The yauaminni then led him round and round the men who were standing in the middle of the ceremonial ground, and then his father linked the boy's right arm in his own left and, preceded, by a younger brother of the father, the two marched round and round, the father telling the son that they had put the armlets on him, that he was now a Watjinyerti, and saying repeatedly: "They can see you like this!" By this time all the women and children were gathered, round the ceremonial ground and the mia-mias had been built. The lubras sang, repeating what the men sang first and every now and then one or other of the older women called out to the boy, telling him to follow his father and his yauaminni. This went on till late in the afternoon when all the men left the ceremonial ground, the women and children following a short distance behind. It was pouring in torrents and the ground, in many parts, was running with water, through which we squelched along, pressing our way, drenched to the skin, through the dripping scrub and tall grass. Close to the water pool a halt was made at the base of a gum tree, where some green boughs had been piled up against the trunk. They were pulled aside and, under them we found the three Marukumana boys crouching. What this part of the ceremony meant we could not discover. However, after much gesticulating and pretended surprise, the party moved on, taking the boys with them ,until they came to the stream which was now running. The yams were in a little side pool with logs placed on the pitchis to prevent them from floating away. They

{p. 99}

were inspected and then, suddenly, several old men seized the Watjinyerti, plunged into the water with him, and rushed backwards and forwards, some having hold of his legs and others of his arms. In this helpless state he was dragged backwards and forwards several times, for the most part completely immersed in the water. When they released him they turned their attentions to the Marukumana boys, who were made to lie down in the side pool (Fig. 31). First of all each of them had his head put into a bark pitchi, along with a few yams, and then, in this uncomfortable position, he was held under the water, which was very muddy, for quite half a minute. As the yams had "whiskers," their close associations with the heads of the boys was supposed to be efficacious in stimulating the growth of hair on the faces of the latter. The boys were then made to stand up and, to assist further in the growth, each one had his chin rubbed hard with a hairy yam and then freely bitten by any older man who chose to do so. This ceremony is called Tunima irruwinni. They were very sore and uncomfortable when it was all over and, to add to their discomfort, they were sent away to a mangrove swamp, close by, to have their chins rubbed with the evil-smelling mud. The women and children had been watching the performance and, after the immersion of the Watjinyerti, four of them, two mothers and two sisters, jumped into the water and gave themselves a good ducking.

All returned to camp, the Mikinyerti, Watjinyerti, and the men gathering together on the ceremonial ground, the men, at first, dancing about and clanging their sticks and repeating, time after time, "we have been to the water and washed."

By and by, the Marukumana boys came up from the

{p. 100}

swamp and went into a little mia-mia just outside the ring of earth, the Watjinyerti sitting down in another by himself, watching the men who began to perform dances and listening to the singing that went on at intervals all night.

Early next morning they were busy and, at six o'clock, started to build a special fire in the middle of the ceremonial ground. They took a number of stakes, from five to seven feet in height, and fixed them upright in the ground so that they formed a circle, about three or four feet in diameter (Fig. 32). Within this they piled up wood to a height of four feet and, on the top of this, they placed a thick layer of broken up white-ant hill. What, was the meaning of this we could not find out. Then for an hour they danced round and round it but did not attempt to light the fire. The women and children were watching them all the time. Soon after seven o'clock the men left the ground and, in single file, started off for the water pool. We were soon, once more, drenched to the skin. Nothing special took place; the yams were taken out of the water and carried back to the ceremonial ground by the Watjinyerti and the Mikinyerti and placed in two heaps, one on each side of the fire. This is always done, but the natives do not know why. Then the fire was lighted by the Mikinyerti and Watjinyerti boys, the Mikinyerti's father and the Mikinyertinga girl. It took them a long time to do this, because everything was soaking wet and pools of water were lying about on the ceremonial ground, while the natives were dancing in sloppy mud. On the way back from the water pool, the men cut a quantity of long grass stalks, which were placed on the top of each heap of yams. The three Marukumana boys, as before, were in one mia-mia and the Watjinyerti in another. The dancing and singing went on and,

{p. 101}

one occasion, the father took his daughter, the Mikinyertinga girl, by the hand and led her round several times. The fire was burning but, for more than an hour, nothing was done to it or to the yams. The Watjinyerti was surrounded by a few men who pulled out all his pubic hairs and also those on his upper and lower lip. While this was going on, the operators were singing the simple refrain, "too bad, pull out hairs," which was repeated by one woman, who was the daughter of the brother of the Watjinyerti's mother. The main body of men were walking round and round the fire, striking their buttocks and singing fiercely at intervals. At the end of about an hour, the men went to the fire and drew out lighted sticks which they threw away, first facing towards the north and then the south. Then once more they sang, the women outside the circle joining in. Taking small boughs, the men now approached the fire and beat it down from above, the idea of this being to cleanse it of all evil influence--if this were not done they believe the evil would go inside them and they would break out all over sores. While doing this they yelled, Brr! Brr! Brr! ee! ee! Some of the grass stalks were then tied into a rope, long enough to encircle the fire, around the red hot embers of which they were placed, after the latter had been raked over, together with the hot lumps of ant hill, and made more or less smooth. The idea of this was to prevent the yams from falling out of the fire. The remainder of the grass was placed over the embers and the yams put on top. Sheets of paper bark were spread over them and these, in turn, were covered with damp earth which was dug up with yam sticks, in a circle round the fire. No women placed any yams on the fire. While this was in progress, the greater number of the men stood round shouting, Brr! Brr! Brr! Oh! Oh! The men who

{p. 102}

placed the earth on the fire, smoothing it down to make a more or less regular low dome-shaped structure, eve,, now and again knelt up and threw their bodies and arm, back, while the onlookers yelled a specially loud Brr! Brr! and struck their buttocks fiercely. When the mound was completed, everyone retired to the margin of the ground; some sat down, others stood up and all of them continued singing and striking their buttocks. After a pause, one man came out and performed a special shark dance, the audience beating time. Then one old man, who took the lead and was always in front in the processions, walked slowly round and round the fire, singing of the yams and the grass. Every now and then he went outside the ceremonial ground and, with both arms held up, told the women what to sing. It was just as if a wild hymn were being sung and the verses given out, one by one. The men were chanting continuously and, every now and then, the shrill tones of the women came in. The three Marukumana and the Watjinyerti remained in their mia-mias and the singing went on for about two hours till the yams were cooked. The men then sat down round the fire and the yams were taken out (Fig. 33). The four young girls and two old women, the mother and father's sister of the Watjinyerti, were called up and were given yams to skin. Any man, apparently,, was allowed to do this and also the Watjinyerti, but not the Marukumana boys, who were not even painted. The little Mikinyertinga girl, after skinning hers, handed then, to her father. After the skinning, the yams were cut up into slices, an operation which occupied a long time. It was, of course, done on the ceremonial ground and, while it was in progress, one man was walking round and round, striking sticks together, while the others chanted. The men sang, time after time, "yams, you are

{p. 103}

fathers." The natives said that, as a result of the performance of the ceremony, all kinds of yams would grow plentifully--not only the kolamma, but, more especially, other kinds which, as articles of diet, are more useful to them than the kolamma, which is very hot and needs special preparation. This one kind of yam is not much used by the Melville and Bathurst Islanders but is a favourite food amongst other tribes on the mainland. The Island natives evidently regard the kolamma, probably because it has to be specially treated before being safe to eat, as a superior kind of yam, endowed with properties such as the ordinary yams do not possess. If a boy sees this ceremony and afterwards does not do what he is told to do by the old men when he is being initiated, he becomes very ill and dies.

The father of the Mikinyertinga girl took some slices of yam in his hand and the daughter poured water on them from a palm leaf basket, after which the man rubbed the daughter's hair with them in order to make it grow. This over, the four girls retired from the ceremonial ground. Then the men crunched some of the slices in their hands and rubbed their own beards with them. This is called tunima ubabrulua. The sister of the father of the Mikinyertinga and the mother of the Watjinyerti rubbed each other's heads and faces with yam slices., and, when all the rubbing was over, a general decoration of men, women, and children began. The Watjinyerti was painted by a yauaminni man, and had his hair, a band across his nose, and a band down each cheek, white. His armlets, bamajinni, were red-ochred afresh. The Mikinyerti youth had his hair, a band across the nose, and such beard and whiskers as he possessed, painted yellow. The three Marukumana boys had their faces Painted black. As soon as the slicing of the yams was

{p. 104}

over, a small mia-mia, made of sheets of bark and gum tree boughs, was built close beside the remains of the fire, and into this the men put the Watjinyerti and the Marukumana, in order that, so the natives said, they could not be seen by the women. This mia-mia is called malanni, the usual term for one being irruwunni. This may perhaps be a remnant of an aspect of the ceremony which, at one time, was more strongly developed than it is now on Melville Island, and that is the seclusion of the initiate, so that he is not seen by the women and children, who believe in many tribes that during the initiation ceremony he is taken away by a spirit and made into a man.

While the boys were thus hidden, the painting went on, one or two of the old yam men keeping up a continuous chant referring to the yams and the grass. The father painted the Mikinyertinga girl yellow all over (Fig. 34); another girl had one side of her head painted white by her mother and the other side yellow, above one eye she had a white line, and below, a yellow one, and vice versâ on the other side. If both yellow and white were used, as was often the case, the right side was always white and the left yellow. The old leading man had one side of his hair white, the other yellow, the whole of his face was red, save for a yellow band across the forehead just above the eyes, and a white band from ear to ear across the bridge of the nose. His upper and lower lips were clean "shaved," but a strong fringe of beard was made to project all round by means of the sticky sap of the milk-wood tree, and was edged with white down. This design, together with a red ochred body and long sinuous lines of white and yellow from his shoulders to his knees, gave him a ferocious and remarkably weird aspect. Another of the older men had one side of his hair white, the other yellow, and a broad

{p. 105}

median band of red right across his hair, down the middle of his forehead, nose, lips and chin, and then on to his projecting beard, which on one side was painted white and on the other red. The rest of his face was a somewhat lighter red than the median band. Some of the men had their bodies all covered with yellow, others with red, and one or two with black. In most cases they had sinuous lines of white and yellow or yellow and red, and sometimes all three, which usually began at the elbow, ran up to the shoulder, and then either close together down the back on either side to the knee, or else looping over one another. If the white was outermost on one side, it was innermost on the other, this alternation of colours being most striking and characteristic. All the designs were decidedly ornate and quite unlike any that I have seen amongst other Australian aboriginals. They are, however, though decidedly elaborate, very roughly drawn in comparison with those used during the sacred ceremonies of such tribes as the Arunta and the Waramunga.

While this was going on the singing was continuous, but what was sung was very simple. One old man suddenly shouted to the women, "I have painted my daughter's hair yellow." Another old man came out from the ceremonial ground, went near to where a number of women were grouped together, and sang out to them, "I have painted one side of my daughter white and the other side yellow." In one case, the two wives and daughter of an old man were a little way off in the scrub, painting themselves in their mia-mia. The old man kept coming out from the ring and walking round so that they could both see and hear him, and time after time they sang out, repeating what he said, which was merely a reference to the painting. The women, in

{p. 106}

most cases, simply daubed red or yellow ochre over themselves, with little attempt at design. When the decorations were complete, there was a short pause, and then the men began to walk round and round the ground, singing and clanging sticks with their arms uplifted as usual. Then one man "sang." the Mabanuri, or shooting star, which is supposed to be an evil spirit. The object of this singing was to protect the boys in the mia-mia against its evil influence.

Also they sang the bamajinni, that is the armlets of the Watjinyerti, which is also supposed to aid in protecting him against any shooting star. This over, several men walked round and round the mia-mia containing the Watjinyerti, singing of an attack upon it by spears. At this stage, the old leading man was standing up and giving orders. He, and another man, danced wildly round and round the mia-mia while the men, with special vigour, struck their buttocks, yelling and stamping loudly as they did so. It was a crocodile dance, and the old man carried a ball of red ochred down in his hands, throwing it up every now and again to represent fish jumping out of the water in front of the crocodile. This was followed by a shark dance, performed by a man with a blackened body and long sinuous lines of white and yellow spots. These were the best dancers and they entered into the performance with zest, dancing and stamping, round and round, until they were exhausted. Then came a curious part of the ceremony, quite unlike anything that is known in connection with initiation on the mainland. The father of the Mikinyertinga girl had previously decorated her with red and yellow ochre. He now called her up and spent some time in building up kind of mop of hair on her head, by means of twisting into her own hair a large number of little curled strands

{p. 107}

of human hair. The result was a great mop, calling to mind, on a small scale, that of many Papuans. Then he placed on her forehead a curious chaplet. It is made of a piece of bamboo bent round so as to fit the head closely from ear to ear, across the forehead, somewhat like a tiara. On to it were fixed a series of flattened tufts of dog tail hairs--the hairs radiating from a central disc of beeswax. Decorated with this mop of hair and the chaplet, the girl was led by her father to the mia-mia and put inside this with the four boys. It was a tight fit, and they were all closely huddled together. Then there came another shark dance, accompanied by a song, consisting of the repetition of the simple refrain, "the shark has a big mouth. The salt water makes the shark's mouth big." This was sung by a man of the Pandanus (screw-pine) totem. Then came a devil-devil dance called Mabanuri (shooting star). This was followed by a march round and round the mia-mia, the men gradually getting more and more excited. They were supposed to be a hostile tribe, coming to kill the people in the mia-mia. The men began to prance about and, after a minute or two, the bark sheets were opened up, so that the girl and boys could be seen. Then they were closed up again and a mock attack, with spears, was made, the occupants being supposed to be killed. After this there was a regular pandemonium, everyone dancing and yelling at the same time. This went on for some minutes and then, when they were thoroughly wound up and excited, they divided into two parties, the older men in one and the younger men in the other. just before this the mia-mia had been pulled down and the occupants came out, the girl and the Marukumana going to one side--in fact leaving the ceremonial ground. The father took charge of the chaplet. {p. 108} The Watjinyerti joined the younger party, as did also the Mikinyerti youth. At first, they had a long pole at which each party pulled, much as if it were a tug-of-war, but this was soon thrown away and then they mingled together, forming a wild, excited mass of yelling savages, heads, arms, legs, and bodies all mixed up, until, at length, one party succeeded in pushing the other, slowly, along while they yelled Brr! Brr! They undid themselves and the performance, called Arri madjunderri, came to an end. The men gathered again round the remains of the fire and the old leader took hold of the Watjinyerti's arms, behind his back, and led him round the fire. There was some more dancing, the men standing round the margin of the ceremonial ground, and then the leader came out into the middle, picked up some remnants of the fire, and threw them away in various directions. This was supposed to be emblematic of the throwing away of sickness. Then they set off for the water hole, in single file, the Watjinyerti and the Mikinyerti carrying the yams. The Mikinyertinga and the Mikijeruma girls and the two old women accompanied them, the other women and children came on behind and stood a little distance away. When they reached the water hole, the yams were put in the water, together with the roots or "whiskers" which had been carefully preserved and were "sung." Then an extraordinary ceremony took place. Most of the men began to pluck their beards and whiskers out (Fig. 35). They began at the ear on each side and went down to the middle of the chin, plucking the hair out in bunches. Some did it for themselves, some allowed others to do it for them, and not a single man seemed to flinch in the slightest degree during the performance of what must have been, at all events, a decidedly uncomfortable operation. A strange thing was that no bleeding seemed to

{p. 109}

take place. When it was over the hair was placed in the pitchis, together with the sliced yams and their "whiskers" and left in the water for the night. Early next morning, everyone was astir and the decorations were renewed. Then they all set off for the water hole, in single file as usual. A halt was made, before they reached the water hole, at the base of the tree at which the Watjinyerti had previously been secreted. Acting under instructions from the old leader, a Marukumana boy and the Mikinyertinga girl had left the camp and were lying concealed by boughs, at the foot of the same tree. The father of the girl placed the chaplet on her forehead and gave her a ball of red-ochred down, called Taquoinga--the same one that he had previously used in the crocodile dance--hanging it round her neck with a string. This done, the whole party came on, the bushes were thrown aside, and everyone simulated the greatest astonishment. The boys came out first of all and danced about, within a circle formed by the men, who sang and struck their buttocks. Then the girl came out and danced round, accompanied by four men, her father and three of his brothers. The girl carried the Taquoinga in her mouth, because she was supposed to be shy and it gave her courage. A ball of this kind, called Ballduk by the Kakadu, is very often seen, suspended from the necks of the men, both on Melville and Bathurst Islands, and on the mainland, and is always carried in the mouth and bitten hard, at times of great excitement, such as during a fight. After this little ceremony was over, the whole party moved on to the water hole, the yams were taken out and carried away to the camp, the hairs and whiskers being left behind. The natives, apparently, have no fear of anyone securing the hair and working evil magic with it. In camp, everyone partook of the yams and

{p. 110}

they were all supposed to begin eating at the same time.

The Watjinyerti was painted red and, for some time, he had to keep away from the main camp. We used to see him sitting about in the scrub, a rather forlorn looking creature, bright red, because he was completely smeared over with ochre, and wearing the armlets. In addition to these, he now wore a strange necklet called Marungwum. It was made of a round stick about half an inch in diameter, bent into the shape of a horseshoe, the two ends being capped with knots of wax and tied together with hair string, from the middle point of which a long string, ending in a tassel, called paraminni, hung down the middle of his back. He wore this continuously after the ceremony was over, for six weeks, when a new one, called Illajinni, was made, which, in its turn, he wore for four months. The natives have no idea as to what is the significance of the necklet, except that the Watjinyerti always has worn it and that, if he took it off, he would become seriously ill. Certainly, together with his red-ochred face, it makes him a very prominent and distinctive object. When the ceremony was over, the mother of the Watjinyerti had to wear a necklet similar to his and was obliged to keep it on as long as he did. The natives say that, if the mother's fell off, the boy would become ill, and that if the boy's should fall off the mother would be ill. After these ceremonies were over, the ceremonial ground was deserted. The mia-mias that had encircled it closely were removed some distance away into the scrub. Three days later, while the natives were busy painting posts) to place on the grave of a man who had died a year ago, they gathered together, close by the posts, and the young Marukumana were brought in and thrown up in the air. The idea was to make them grow tall. On the morning of the next day

{p. 111}

the men again assembled at the grave posts and lighted a fire at the base of a blood-wood tree, close by. Four boys, two of them Marukumana and two younger ones, were made to climb up the trunk. Green boughs were placed on the fire, from which a column of smoke arose, called kujui. The same word is applied to a water spout, which it is supposed to represent. Each of the boys, in turn, had to climb down. The two younger ones were allowed to jump over the fire but the Marukumana had to pass through it.

The above ceremonies took place during the second week in March. I was unable to see the subsequent proceedings, but during a later visit to Melville Island was informed that what took place was as follows:--My informant, one of the natives, was present and secured for me the various ornaments. The Watjinyerti remained away from the main camp until the end of April, when he came into his mother's camp, took off his old ornaments and washed himself in salt water, brought up by his mother. New ornaments were put on him, including a special belt called Olturuma, which was made by his mother's brother. He kept all these on until the performance of a final ceremony in September. On this occasion he sat down in camp with his mother, with all his ornaments on. His mother sang out to the older women, especially his "sisters," to come up. They did so and took half of the ornaments off and then the older men came up and took the remainder off. When this was done the Watjinyerti danced a little. A Yauaminni man took the ornaments--armlets, necklets, and waist girdles--and placed them all on a special platform of branches, built like a big nest, in an iron-wood tree. While this was being done, everyone stood round the mother and the Watjinyerti, who were in the middle. {p. 112} Everyone, men, women, boys, and girls, cut their heads and cried. With this the ceremony came to a close.

The various articles worn by the Watjinyerti boy, the Mikinyertinga girl and the mother of the boy are shown in Plate 1. [Ornaments Worn During Initiation Ceremony On Melville Islane] Figs. 1 and 2 represent the special belt called Olturuma. Both of them are twenty-six inches in length and very strongly made out of alternate blocks or panels, as it were, of human hair and banyan bark string, their edges being sewn all round with split cane. This bark string forms a strong loop at each end, where it is covered with beeswax that has been whitened with pipe clay. in the upper one the blocks of human hair string are left uncoloured, those of banyan bark string are red-ochred and outlined and crossed by lines of white and yellow alternating in the way characteristic of Melville and Bathurst Island decorations. The lower one shows a somewhat more complicated scheme of decoration, some of the human hair blocks or panels being red-ochred. The centre of the belt is marked by a white circle; on each side of this is a red panel, then an uncoloured banyan-bark string panel, then a pinkish-cream coloured panel, the pigment being made by mixing pipe clay with red-ochre; this is followed by a red panel, then a long one of banyan string, partly coloured, partly uncoloured; on the right side is a long human hair string panel, running; to the end, but, on the left, the terminal panel is made of banyan bark. The design is symmetrical in the central part of the belt, but slightly asymmetrical towards each end.

Fig. 3 represents the ornament worn by the mother. It measures twelve by thirteen inches. It consists of a stick about three-quarters of an inch in diameter bent so as to form a semicircle. It has been completely smoothed and red-ochred and its two ends are held

{p. 113}

together by strong strands of banyan bark string, bound round and round so as to form a strong bar which is completely coated over with beeswax and decorated with alternating bands of red and yellow ochre, outlined with white. By way of ornamentation there is, on each side, a knob of wax studded with abrus seeds. From the middle of this transverse bar an elaborate pendant hangs down. Its total length is eighteen inches and it consists of a large number of strands of banyan bark string gathered together into two cords to form a loop half-way down the pendant, the strands being enclosed in beeswax, one side coloured red, the other yellow. The attachment of the pendant to the bar is marked by a ring of wax covered with abrus seeds. Then follows a curious disc, two and three-quarter inches in diameter, with short, stiff strands of human hair string radiating all round. For an inch and a half beyond this the string is enclosed in wax coloured yellow and red, then for two inches and three-quarters the string, which is red-ochred, is free. This is succeeded by the central loop, which is ornamented at each end with a circle of abrus seeds, stuck in beeswax. The length of this part is four inches and a half. Then for three and a half inches the strands are free, after this follow a circle of abrus seeds, then a length of string, two and three-quarter inches, covered with wax, painted red, white, and yellow. This is succeeded by a second disc made of a series of cane rings fitting one inside the other, with stiff strands of human hair string radiating all round. The disc, as can be seen,, is decorated with alternating, radiating lines of yellow, red, and white. Finally the Pendant terminates in a sphere of delicate, light brown coloured down feathers.

The structure is worn in such a way that the pendant hangs down the middle of the back.

{p. 114}

Figs. 4 and 5 represent, respectively, the necklets called Marungwurm and Illajinni, worn by the Watjinyerti boy. The smaller one measures six and a half inches by six, the larger one eight inches by six and a half. They are quite simple in form and made, essentially, in the same way as the larger one worn by the mother. One of them, the one that I saw the boy wearing, has a pendant of thirty-four strands of red-ochred human hair string. The other is ornamented with two knots of beeswax, each two inches long and thickly studded with abrus seeds.

Figs. 6 and 7 represent the ornaments worn by the Mikinyertinga girl. The first of these is in the form of a curious chaplet, made of strands of human hair string that are all flattened out and covered with beeswax so as to form, roughly, a semicircle about eight inches in external diameter. Radiating out from this semicircle there are eleven wild dog tall tips which are also flattened out. The girl wore the chaplet on her head as if it were a tiara, the semicircle of wax passing across the front of her hair from car to ear, the strands of hair string being tied together behind her head. The second has the form of a ball measuring three and a quarter inches in diameter. It is very cleverly made out of the lower parts of feathers that have been cut in half so as to retain part of the stiff barbs and all the down portion at their bases. The cut ends in some way, are closely and firmly attached in the centre of the sphere, but it is so compact that, without destroying it, it is impossible to ascertain how they are actually attached. The projecting end of each is the quill end, so that the sphere which is composed of hundreds of feathers looks like a ball of down. The feathers have been orange-coloured with a mixture of red and yellow ochre. The girl wore the ornament round her neck, attached by four strands of human hair string

{p. 115}

during the performance of her dance, held it tightly between her teeth. It is called Taquoinga, the same name being applied to the little spherical bag that the men carry round their necks and place between their teeth during times of especial excitement.

In the Port Essington tribe there are two important ceremonies connected with initiation, the first of which is called Naialpur and the second Wokungjari; these terms indicating also the status of the individual who has passed through one or other of them. The following account was given to me by a Port Essington native who was living in Cooper's Camp on Melville Island and was well acquainted with the customs of the latter people as well as with those of his own tribe.

The central figure of the Naialpur is a youth who has reached the status of Ngauunduitch and is perhaps fifteen or sixteen years old. He is the equivalent of the Watjinyerti on Melville Island, and there are also younger boys who take a secondary position in the ceremony. They are called Namungulara and are the equivalents of the Marukumana boys. These boys may evidently take part in the ceremony several times before they become the central figure. There was one Port Essington boy in the camp on Melville Island who was not more than thirteen years of age and he had twice been Namulugara.

The elder men, that is the Wokunjarri and Balquar akkan, consult and decide upon the initiation of the youth. A man who is the latter's pappam comes to him and says "gun mi araman," I want you. This is done in the camp, and the kamu (mothers), wulko and munburtji (elder and younger sisters) cut themselves and cry. When it has thus been decided to advance any youth from the status of Ngauunduitch to that of Naialpur he is sent out to visit camps under the guardianship of a man who has

{p. 116}

already attained the latter status. They each carry a very simple wand, merely a stick about four feet long, called uro-ammi (Fig. 36),and when they come within sight of a strange camp, they halt and, bending towards one another over the wands, chant a refrain the significance of which is well understood.[1] The women in camp reply with the call "wait ba; wait ba," and so long as the youths remain in any camp, they periodically repeat their refrain, the women always answering with theirs. When the Ngauunduitch and his guardian Naialpur return they are taken to a special camp called koar, where a ceremonial ground has been prepared. The latter is about thirty or forty yards long with the sand banked up all round, and on one side a track leading into it with its sides also slightly banked up. In the middle of the ground is a bush wurley called wangaratja with a forked stick standing upright on each side and a hollow log within it. The men's spears are bunched together and rest against the side of the wurley. The first night the Ngauunduitch spends, under the charge of a pappam, close to the entrance of the koar. Early in the morning he is taken on to the ground and sits down beside the log which has been removed from the wurley. This special log is called piruakukka, a name that no lubra may bear. The usual name for a hollow log is aranweir. At first the younger boys are present and the pappam men dance round and round them and at times pinch their cheeks to make their hair grow. This is in the very early morning, after which they are taken back to the camp and the men set to work to decorate themselves for the performance of ceremonies on the koar.

The Ngauunduitch, both now and during the time that he travels over the country from camp to camp, wears

[1. A fuller account of this is given later in connection with the initiation ceremonies of the Kakadu tribe.]

{p. 117}

special waist girdle called agir-agir. It is made of a cord of human hair string from which short lengths of string, arranged in pairs, each about eight inches long and ending in little knots of beeswax, hang down. During the ceremony, also, both the Ngauunduitch and the Namungulara wear necklets called leda. Each of these consist of a circlet, large enough to go comfortably round the neck, made of vegetable fibre string, such as that derived from the banyan tree bark, or it may be made from the hair of a young man. The strands of strings are gathered together to form a pendent that hangs down the middle of the boy's back. Where the strands come together on the circlet, there is a coating of beeswax and the pendent cord is also ornamented with two or three circles of the same material. In the case of the younger boys, the Namungulara, a small length of bamboo, is attached to the free end of the cord. In some mysterious way this is supposed to represent the boy's knee, and the wearing of it during the ceremony has the effect of strengthening the knee. At a certain point in the ceremony, also, the Namungulara boys come into camp and place their ledas on the heads of their mothers, which is a sign to the latter that the ceremony is nearly over and that they must go out into the bush and collect yams. When the men are ready the pappam takes the Ngauunduitch[1] back to the koar in the middle of which all the decorated men stand round the wurley. When he reaches the entrance to the wurley the men yell Prr! Prr! The men are painted so that their faces cannot be recognised and, at first, the youth is frightened because he has seen nothing like it before. The men

[1. There are often two or more youths passing through the ceremony at the same time, in which case they sit down in a row with a pappam in charge of each.]

{p. 118}

arrange themselves round the margin of the koar and then they dance, one by one. This over they pull the wurley to pieces and dance on the remnants. Th, boy is then taken back to his camp by the pappam. At night he returns to the koar and ceremonies are performed connected with the totems, kangaroo, cockatoo, crocodile, lizard, etc. At the close of each one they dance on the remains of the wurley and finally lie down on them, some of the bushes being piled on the top of the old men. The natives have no idea of the meaning of the wurley or of breaking it down. While this is going on the pappam sing:--

Nan o tjeri nilkil

Binyung mi

Bin yalli nalli

Tjai Tjo---o------!

Then the old men get up from the bushes. Bunches of cockatoo feathers are placed on the boys' heads and then the ceremonies go on, the pappam singing--

Natjat pula pula

Bin yung mi

Bin yalli nalli

Tjai Tjo---o------!

repeating it time after time until they are tired out. The men now arrange themselves in a long row and then crouch down with hands on knees, all swaying about from side to side and whistling in imitation of the wind. Then they stand up, everyone waving about like a tree in the wind; in fact they are supposed to represent big gum trees. Time after time they repeat the refrain "Natjat pula pula," etc., and then they all fall down on hands and knees and move along in a line around and behind the youth surging and swaying from side to side and yelling Arr! Arr! until at last, with a final loud

{p. 119}

Ai kai ai: ai kai ai: ai-------, ending in a long descending note, they fall down round the hollow log. The boy is then made to sit by the side of the latter with the men all round him. The old pappam men sing out

Birringin, birringin, birringin,

Urqui pit, urqui pit,

Alor! alor! alor!

The whole is repeated several times and the day's performance comes to an end, the boy being taken back to his camp to sleep. Early next morning they are back on the koar and are shown first a crocodile ceremony. One old man sits on the log and the others on the ground close by, singing,

Wungaka wunga birri

Birridji ja djaquia.

The boy stands by and watches. Two men, imitating the movements of a crocodile, sprawl on the ground and crawl along to the remains of the wurley. The man on the log sings out Wau, Wau, which is the signal for an old man to knock down the forked sticks. This knocking down is called numulana. Later on a cockatoo ceremony is shown.

It is during the performance of these ceremonies that the boy is shown the bull-roarer, called by this tribe Kurrabudji. He sits down on the koar ground with his head bent low so that he cannot see what is taking place. Some of the old men paint themselves and come up behind him whirling the bull-roarers. The pappam tells the boy to look up, and then he sees the men and is told that the noise is made by the Kurrabudji. As usual the lubras think it is the voice of a great spirit that takes the boys away, but the old men tell him that it is not so. At first he is very frightened, but the old men show him

{p. 120}

the sticks and, after having rubbed their own bodies with them, place them in his hands. The boy looks at them, and then hands them back again to the old men. He is repeatedly shown the Kurrabudji and warned that the lubras and children must not see them on any account. At times also the boy is rubbed over with the sticks. In addition to this the old men often rub the heads and cheeks of the Ngauunduitch and Namungulara with their hands to make the hair and whiskers grow. Fat is also rubbed frequently on their private parts to make then, strong, and they are told that they must not growl at the old men, and must not take a lubra until they are older and have passed two or three times through the Naialpur.

The showing of ceremonies continues for five or six weeks, after which a visit is paid to the lubra's camp. The Naialpur is in the centre of the procession with the pappam and other men round him. They shout loudly Kor yai, kor yai, so as to tell the lubras that they are coming. Then, when quite close to the camp, they yell wha, wha, wha! At the camp the lubras are arranged in two rows with a strong forked post, called quiaramba, fixed upright in the ground. On this two young women sit, crying out leda, leda, which means "string, string," some of which they hold out. The same name "leda" is given to the head rings of the Namungulara boys. The two girls are either sisters or sister's daughters of the Naialpur. When the men are about twenty yards away they come down from the post and all the women sing Kait ba, Kait ba, moving their hands and knees as if to invite the men to come on. The Naialpur and Namungulara wear opossum fur-string armlets, human hair-string girdles, the special chest girdles, called man-ma-ouri, which encircle the shoulders, chest, and neck. They also wear the head rings called leda, and a pubic tassel. The {p. 121} Naialpur stands quietly beside the forked post while the men dance between and round the two lines of women. The pappam then leads the Naialpur to his father and mother, who are at the far end of the camp, and seats him between them. Then the boy's sisters come up and a general walling ensues, after which the Naialpur is once more taken into the bush.

The second ceremony, called Wokungjari, is passed through after a man is married, sometimes before, and sometimes after he has a child. In the case of my informant it took place before. A pappam tells the young man to come with him into the bush, which he does, leaving his wife in charge of his father and mother. The pappam supplies him with food and he is supposed to be dependent on the old man for this, so that sometimes he may have plenty, but at others very little, depending entirely upon how much the old man has either the ability or the desire to secure. He is very often shown the Kurrabidji and every now and then his father comes and looks at him, but no one else, and he must not go anywhere near his lubra. Every day the pappam rubs him over with fat, and he spends practically all his time on the ceremonial ground, where he is shown and allowed also to take part in the performance of totemic ceremonies. This goes on for two months, at the end of which time the pappam tells him to go and bathe, and show himself to his father and mother in the Main camp. He is now a Wokungjari or fully initiated man.

The Kakadu is one of a group, or nation, of tribes inhabiting an unknown extent of country, including that drained by the Alligator Rivers, the Coburg Peninsula, and the coastal district, at all events as far west as Finke Bay. Its eastern extension is not known. For this

{p. 122}

nation I propose the name Kakadu, after that. of the tribe of which we know most.

The initiation ceremonies are evidently closely similar all through this group of tribes. In different parts of Australia these ceremonies vary to a considerable extent. In the south-eastern and eastern coastal tribes the ceremony consists in knocking out a front tooth. In the central and north central and also in some of the western tribes, there are two ceremonies which often follow close upon each other. At the first the rite of circumcision is carried out and at the second that of subincision. In some of these tribes only the first of these is practised. In the Arunta and other central tribes, the youth is regarded as initiated and is allowed to see all the sacred ceremonies as soon as he has passed through the two ceremonies named, but, at a later time, he takes part in what is called the Engwura, which consists, partly, in the performance of a long series of sacred ceremonies referring to the totemic ancestors, and partly in a curious ordeal by fire, after which he becomes a full man, or, as they say, ertwa murra oknira, which words mean man, good, very. He only takes part in this when he is adult. In the Kakadu nation there is a succession of no fewer than five series of ceremonies, the last of which only adult and comparatively old men may witness. They are performed in the following order and are known respectively as

1. Jamba.

2. Ober.

3. Jungoan.

4. Kulori.

5. Muraian.

Of these the first may be regarded, strictly speaking, as the important initiation ceremony. It marks the turning

{p. 123}

point in the life of each youth, when he passes out of the ranks of the women and children, enters into those of the men, and is, thereafter, allowed to see and gradually take part in the performance of the sacred ceremonies that are characteristic of the remaining four, although he is an elderly man before he is permitted to witness the Muraian.

1. Jamba Ceremony.

I was not fortunate enough to see the Jamba initiation ceremony of the Kakadu tribe but a middle-aged man, named Urangara, who was fully acquainted with all the sacred ceremonies of the tribe, described to us what happened in his own case and the procedure as he has witnessed and taken part in it many times since then. just before the rain season, in his own case, his father consulted a few old men, some of whom stood in the relation of father's elder brothers to him and others in that of father's father (Kaka). These men) during the ceremony, are called Kuringarerli. The father said to the old men: "My boy is growing big, his whiskers are coming. It is time he was allowed to eat some of the forbidden foods." The latter is expressed by the words "morpia" (food), meja (eat), kumali (forbidden or tabu). After this, there was a general conversation amongst the older men and it was decided that the time had come for the boy to be initiated. They said to two elder men, Bialilla mirawara muramunna koro, which means the boy is growing big, you two go to the bush. On this occasion there was another youth who was being initiated at the same time and the two elder men took the two youths away with them into the bush, visiting various camps and inviting the strangers to come and witness the ceremony. They stayed away a long

{p. 124}

time until, as Urangara said, tjara numbereba, that is, their whiskers were long. During all this time the two elder men must not look at a lubra; if they did the boys would become ill and also the other men would drive spears into them. The women have to be very careful not to go anywhere where they are likely to come across the youths. The old men instruct them what parts to avoid. After a long wandering, the boys and their guardians return, bringing with them the visitors, whom they gather together as they come to the various camps on their homeward journey. All the men in camp, except a few of the elders, who remain to watch the women and children, go out to meet the party, whose approach is notified by the clanging of sticks. The whole party comes in, except the boys and their guardians. The strangers are conducted to their camping grounds and, early next morning, the men go out and prepare a special ceremonial ground called Tjaina. At one side of this a bush shade, called waryanwer, is made and the men stand, some under the shade, which is six feet high, and open at both ends, and some round the ground. In the centre of the latter is a hollow log called jamba, four or five feet long and about two feet in diameter. The boys are not yet brought to the ground, but one old man sits down and repeatedly strikes the jamba. He is called dabinji wanbui. It is now dark, or mardid, that is, night time. An old man takes two sticks and goes out close to where the boys are camped, striking his sticks together. The men in charge of the boys say, ameina--what is it? and the old man answers, Brau ningari--give us the boys. They reply, Ouwoiya kormilda--yes, to-morrow. Then the old man returns to the camp and all sleep. In the morning they say to the boys, moru kuperkap--go and bathe. The lubras meanwhile have been sent out to gather food--

{p. 125}

lily roots, seeds, etc.--and are told to return at mid-day (mieta). The boys bathe, while the lubras are out of the way in the scrub, because they may not yet be seen by the latter. After this they are painted by their guardians. Each has a circle of white running across, just above the eyes, then down each cheek and under the chin, so that the whole face is framed, as it were, in white. Two lines of red run across the upper part of the forehead. On their return, the women paint themselves; the younger ones must be decorated with red ochre, the old women may paint themselves as they like and very often use yellow ochre. When all is ready, the boys are brought up accompanied by the women, who sing "wait ba, wait ba." The old men cover the eyes of the boys, who walk with their heads bent down. There may sometimes be as many as ten or twelve youths passing through the ceremony, in which case they are brought up in pairs. When they have all come in, the lubras run back to their camp, singing "wait ba, wait ba," swaying their bodies from side to side, like a native companion. The old men, the guardians of the boys, have bushes in their hands which they shake, saying to the boys kulali koregora--look at the sky; jibari koregora--look at the trees; balji jereini koregora--look at the big crowd of men. After saying this they take their hands away from the boys, who look up and see the ceremonial ground, the jamba, the bush shade, and the men standing round. Meanwhile sticks are struck together and the bamboo trumpets sound, making a noise which sounds like a constant repetition of biddle-an-bum, biddle-an-bum. This is a very characteristic booming sound with the two first syllables said more or less rapidly and long emphasis laid on the third. There is considerable excitement and the singing and clanging go

{p. 126}

on for some time, until at last the boys are taken into the bush shade. After a time the old men lead them on to the ground and seat them one at each end of the jamba. The old guardian kneels immediately behind his boy, telling him what to do. He first of all takes a stone and hands it to the boy saying, jilalka podauerbi--here is a stone. Then he says, Ngoornberri jilalka mukara--son, throw the stone. The boys then throw each stone through the hollow jamba, after which they hand them back to their guardians. No one knows why this is done. The guardians say to the boys, Ngoornberri tjaina kumali: jamba kumali koregora: uriauer kumali koregora: which means, son, you see the forbidden tjaina, jamba, or bush shade, as the case may be. Then all the foods that are forbidden, or kumali to them, are named and repeated, Kintjilbara (a snake) kumali, kulori (a yam) kumali, kulungeni (flying fox) kumali, and so on, through the whole list, which includes most of the good things. The boys say nothing and the sun goes down.

When this ceremony is over they are once more sent into the bush, still under the guardianship of the old men. The other old men remain in camp, performing ceremonies, and the women go out gathering food supplies. If the boys chance to hear the lubras talking, they must immediately bite up some paper bark and stuff up their ears with it. On no account are the initiates allowed to eat any food that has been secured or handled by women; everything that they eat must be given to them by their guardians.

The ceremonies are carried on in camp for about five moons, and during all this time the boys are in the bush. When it is decided to bring them back, certain of the Numulakiri, that is, young men who have previously passed through this particular ceremony and, though

{p. 127}

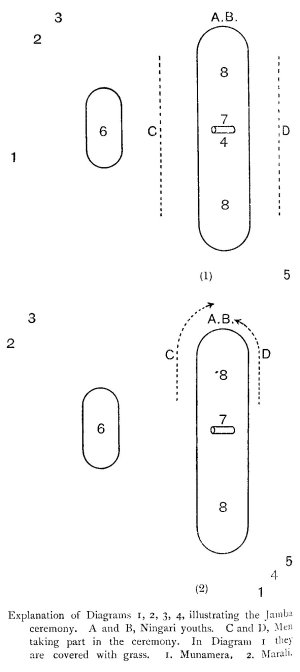

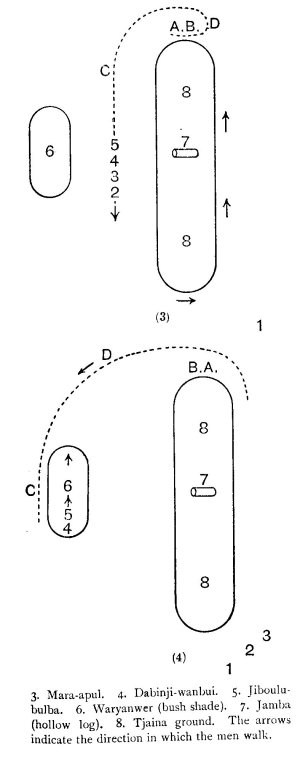

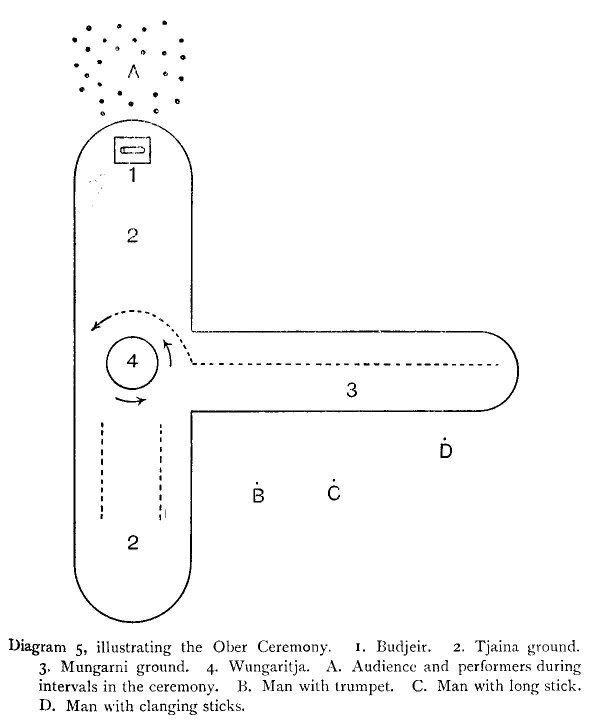

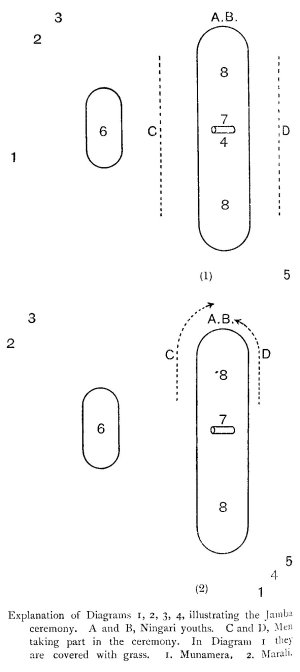

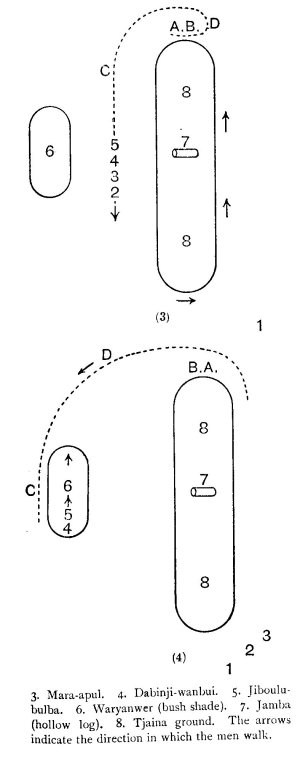

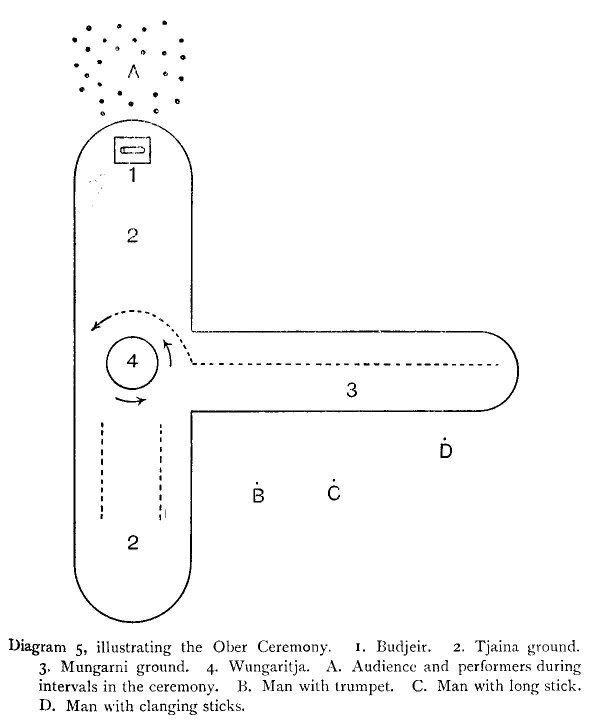

initiated, are not old enough to be allowed to see the final series of ceremonies, called Muraian, are sent out by the old men to bring the Ningari in. The older men who have been looking after them have, meanwhile, joined the others in the main camp. The Ningari boys (A and B) come in, bending forwards, each with a Numulakiri man's hand over his eyes. He is led to one end of the tjaina ground, on which special individuals are placed, during different stages of the performance, as shown in the accompanying diagrams. To one side stands an old murabulba man (1) who is supposed to represent a great old kangaroo ancestor, called Munamera; squatting down by the side of the jamba is a man (4) called dabinji-wanbui; to one side, at the end of the ground, opposite to that at which the Ningari stands, is a man (5) called jiboulu-bulba with a trumpet. In a corresponding position, at the opposite end of the ground, are two men (2 and 3), called, respectively, Marali and Mara-apul. All the rest of the men are crouching down in two lines, one on each side of the ground, and are covered over with heaps of grass stalks (Diagram 1). The arrangements of the performers at different stages can be seen in the diagrams. The native, Urangara, who gave us the account, illustrated it by diagrams on the sand with sticks and stories for men and a minute imitation of the bush shade.

As the Ningari are brought in, the old man, sitting by the jamba, strikes it hard; the trumpets sound and then the men beneath the grass take deep breaths, saying Oh! Oh! imitating the sound supposed to be made by the kangaroo. Then they whistle. The boys wonder what the noise is, because they can see nothing. Suddenly the Numulakiri take their hands away and the boys are told to look up and are warned that all they

{p. 128}

|

see is kumali. The Numulakiri say to them, Tjikaru koiyu koyada--don't talk to Koiyu (mothers); Illaberi legilli koyada unkoregora--don't let the Illaberi (younger brothers and sisters) see (your) spittle; Illaberi korno koyada unkoregora--don't let the Illaberi see (your) excrement; Kumbari koyada kumali koiyu--don't laugh (to your) koiyu (about) the kumali; Unkoregora Tjaina kumali--look or see the Tjaina, (it is) kumali;

|

{p. 129}

|

Tjikaru koyada mareiyu willalu--don't talk (when) you go to the camp; Jam koyada koiyu kumali--don't (eat) mother food, that is, food gathered by a koiyu, it is kumali; Kuderu wirijonga jau--to-day eat wirijonga (various parts of water lilies, roots, stems, seeds); Yakadaitji arongo bararil jau (after) five sleeps eat fish.

During all this time the trumpets are sounding and the dabinjiwanbui man is vigorously beating the jamba, but, after the above instructions have been imparted and many times repeated, the old Munamera man (1) gives instructions to the

|

{p. 130}

musicians to stop and the two men join him at one end and stand close by, where the man with the bamboo trumpet has been stationed. The Numulakiri men then lift the grass off the men who have been whistling, saying, Oh! Eh! Eh! The old men answer with groans and then rise on one knee, stamping the ground and shouting Oh! Eh! Eh! Then, rising completely, they yell Yrr! Yrr! A-Ah! The two lines of men unite together and, led on by the Marali (2) and Mara-apul (3), who join them, they pass, with a curious surging movement, round and round the ningari (Diagram 2) and then round and round the Tjaina ground (Diagram 3). While this goes on the Numulakiri are saying to the Ningari, unkoregora morpiu mirrawarra kumali. Look, the very big morpiu (a general term applied to animals) is kumali; Unkoregora murabulba Munamera kumali, look, the old man Munamera (he is) kumali.

The lines of men are joined by the musicians, while the Marali and the Mara-apul leave them and again stand to one side with the Munamera (Diagram 4). These three men are supposed to represent three great old kangaroo ancestors and are spoken of as Tjeraiober, the latter being the name of the particular series of ceremonies enacted by the old men in connection with the initiation. They have been performing these ceremonies while the boys were in the bush. On the next occasion the boys will be allowed to see them. The men get more and more excited until at last they pass through the bush shade, after surging round and round it, lifting it up, as they do so, and scattering the boughs in all directions) yelling Kai! Kai! Wrr! Wrr! This over, they gather the boughs and grass together and set them on fire, While the fire is burning, the Numulakiri men take the

{p. 131}

Ningari on their backs and dance round and round the fire, in company with all the men, save the three Tjeraiober, who stand to one side, watching. The old men say, Umbordera kala koiyu wari nirwi, illaberi kuballi nungorduwa wari nirwi wilialu mununga, which means, freely translated, to-day you hear your koiyu calling and the illaberi and many women at the camp. Then they say, kormilda mareyida willalu, to-morrow we all go together to the camp; kormilda ngeinyimma kupakapa, to-morrow you bathe, balera kuderi, afterwards red ochre.

That night they camp near the Tjaina. The old men 1 have made armlets and hair belts and, on the next day they say, Bordera ngeinyaminna[1] kujorju, winbegi, to-day you armlets, that is, to-day you wear armlets; Bordera ngeinyaminna gulauer, to-day you wear hair belts. Having said this, they put the belts and armlets on the boys,[2] who wash and are painted with red ochre. Then. one or two of the older men take a piece of grass string and scrape the Ningari's tongue with it, the idea being to cleanse it, saying, nanjil kurrareya, tongue cleansed: tjikaru koiyu pari, mother's talk leave behind. This is done at the Tjaina, where a special fire is made to burn the string and anything that is scraped off the tongue. This brings the ceremony to a close and all the men then leave the Tjaina ground and return to the main camp, where the Ningari camp at one place by themselves. There is no special reception of them by the women. They have to be very careful, however, in regard to the latter. They must not talk to the women nor allow them to see their mouths open. Most especially they must not expectorate in such a way that a woman can see them

[1. Ngeinyimma if addressing one, ngeinyaminna if addressing two, and inyadima if addressing more than two boys.

2. There are two kinds of armlets--those worn on the arm proper are called ualtur or winbegi, those on the forearm are called kujorju.]

{p. 132}

doing it. If they want to do so, they must hold their heads down and cover the spittle with soil at once. They have no idea why, but the old men have always told them to do so. On no account must lubras see their teeth. if they did, their (the men's) fingers would break out in sores. When eating food they turn their faces away from the women and also from their younger brothers, to whom they may not speak. The mothers also tell the latter not to speak to their elder brothers.