READER,--Let us reason together:--

What do we dwell on? The earth. What part of the earth? The latest formations, of course. We live upon the top of a mighty series of stratified rocks, laid down in the water of ancient seas and lakes, during incalculable ages, said, by geologists, to be from ten to twenty miles in thickness.

Think of that! Rock piled over rock, from the primeval granite upward, to a height four times greater than our highest mountains, and every rock stratified like the leaves of a book; and every leaf containing the records of an intensely interesting history, illustrated with engravings, in the shape of fossils, of all forms of life, from the primordial cell up to the bones of man and his implements.

But it is not with the pages of this sublime volume

{p. 2}

we have to deal in this book. It is with a vastly different but equally wonderful formation.

Upon the top of the last of this series of stratified rocks we find THE DRIFT.

What is it?

Go out with me where yonder men are digging a well. Let us observe the material they are casting out.

First they penetrate through a few inches or a foot or two of surface soil; then they enter a vast deposit of sand, gravel, and clay. It may be fifty, one hundred, five hundred, eight hundred feet, before they reach the stratified rocks on which this drift rests. It covers whole continents. It is our earth. It makes the basis of our soils; our railroads cut their way through it; our carriages drive over it; our cities are built upon it; our crops are derived from it; the water we drink percolates through it; on it we live, love, marry, raise children, think, dream, and die; and in the bosom of it we will be buried.

Where did it come from?

That is what I propose to discuss with you in this work,--if you will have the patience to follow me.

So far as possible, [as I shall in all cases speak by the voices of others] I shall summon my witnesses that you may cross-examine them. I shall try, to the best of my ability, to buttress every opinion with adequate proofs. If I do not convince, I hope at least to interest you.

And to begin: let us understand what the Drift is, before we proceed to discuss its origin.

In the first place, it is mainly unstratified; its lower formation is altogether so. There may be clearly defined strata here and there in it, but they are such as a tempest might make, working in a dust-heap: picking up a patch here and laying it upon another there. But there

{p. 3}

are no continuous layers reaching over any large extent of country.

Sometimes the material has been subsequently worked over by rivers, and been distributed over limited areas in strata, as in and around the beds of streams.

But in the lower, older, and first-laid-down portion of the Drift, called in Scotland "the till," and in other countries "the hard-pan," there is a total absence of stratification.

James Geikie says:

"In describing the till, I remarked that the irregular manner in which the stones were scattered through that deposit imparted to it a confused and tumultuous appearance. The clay does not arrange itself in layers or beds, but is distinctly unstratified."[1]

"The material consisted of earth, gravel, and stones, and also in some places broken trunks or branches of trees. Part of it was deposited in a pell-mell or unstratified condition during the progress of the period, and part either stratified or unstratified in the opening part of the next period when the ice melted."[2]

"The unstratified drift may be described as a heterogeneous mass of clay, with sand and gravel in varying proportions, inclosing the transported fragments of rock, of all dimensions, partially rounded or worn into wedge-shaped forms, and generally with surfaces furrowed or scratched, the whole material looking as if it had been scraped together."[3]

The "till" of Scotland is "spread in broad but somewhat ragged sheets" through the Lowlands, "continuous across wide tracts," while in the Highland and upland districts it is confined principally to the valleys.[4]

[1. "The Great Ice Age," p. 21.

2. Dana's "Text-Book," p. 220.

3. "American Cyclopædia," vol. vi, p. 111.

4. "Great Ice Age," Geikie, p. 6.]

{p. 4}

"The lowest member is invariably a tough, stony clay, called 'till' or 'hard-pan.' Throughout wide districts stony clay alone occurs."[1]

"It is hard to say whether the till consists more of stones or of clay."[2]

This "till," this first deposit, will be found to be the strangest and most interesting.

In the second place, although the Drift is found on the earth, it is unfossiliferous. That is to say, it contains no traces of pre-existent or contemporaneous life.

This, when we consider it, is an extraordinary fact:

Where on the face of this life-marked earth could such a mass of material be gathered up, and not contain any evidences of life? It is as if one were to say that he had collected the detritus of a great city, and that it showed no marks of man's life or works.

"I would reiterate," says Geikie,[3] "that nearly all the Scotch shell-bearing beds belong to the very close of the glacial period; only in one or two places have shells ever been obtained, with certainty, from a bed in the true till of Scotland. They occur here and there in bowlder-clay, and underneath bowlder-clay, in maritime districts; but this clay, as I have shown, is more recent than the till--fact, rests upon its eroded surface."

"The lower bed of the drift is entirely destitute of organic remains."[4]

Sir Charles Lyell tells us that even the stratified drift is usually devoid of fossils:

"Whatever may be the cause, the fact is certain that over large areas in Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, I might add throughout the northern hemisphere, on both sides of the Atlantic, the stratified drift of the glacial period is very commonly devoid of fossils."[5]

[1. "Great Ice Age," Geikie, p. 7.

2. Ibid., p. 9.

3. Ibid., p. 342.

4. Rev. O. Fisher, quoted in "The World before the Deluge," p. 461.

5. "Antiquity of Man," third edition, p. 268.]

{p. 5}

In the next place, this "till" differs from the rest of the Drift in its exceeding hardness:

"This till is so tough that engineers would much rather excavate the most obdurate rocks than attempt to remove it from their path. Hard rocks are more or less easily assailable with gunpowder, and the numerous joints and fissures by which they are traversed enable the workmen to wedge them out often in considerable lumps. But till has neither crack nor joint; it will not blast, and to pick it to pieces is a very slow and laborious process. Should streaks of sand penetrate it, water will readily soak through, and large masses will then run or collapse, as soon as an opening is made into it."

TILL OVERLAID WITH BOWLDER-CLAY, RIVER STINCHAR.

r, Rock; t, Till; g, Bowlder-Clay; x, Fine Gravel, etc.

The accompanying cut shows the manner in which it is distributed, and its relations to the other deposits of the Drift.

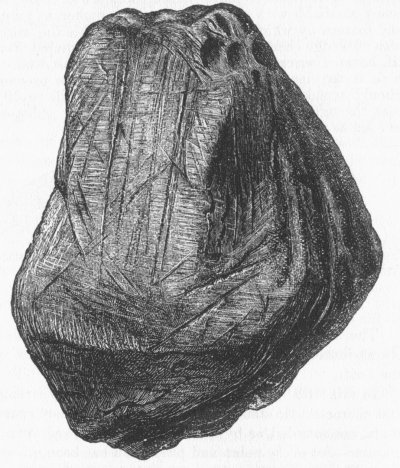

In this "till" or "hard-pan" are found some strange and characteristic stones. They are bowlders, not water-worn, not rounded, as by the action of waves, and yet not angular--for every point and projection has been ground off. They are not very large, and they differ in this and other respects from the bowlders found in the other portions of the Drift. These stones in the "till" are always striated--that is, cut by deep lines or grooves, usually running lengthwise, or parallel to their longest diameter. The cut on the following page represents one of them.

{p. 6}

Above this clay is a deposit resembling it, and yet differing from it, called the "bowlder-clay." This is not so tough or hard. The bowlders in it are larger and more angular-sometimes they are of immense size; one at

SCRATCHED STONE (BLACK SHALE), FROM THE TILL.

Bradford, Massachusetts, is estimated to weigh 4,500,000 pounds. Many on Cape Cod are twenty feet in diameter. One at Whitingham, Vermont, is forty-three feet long by thirty feet high, or 40,000 cubic feet in bulk. In some

{p. 7}

cases no rocks of the same material are found within two hundred miles.[1]

These two formations--the "till" and the "bowlder-clay"--sometimes pass into each other by insensible degrees. At other times the distinction is marked. Some of the stones in the bowlder-clay are furrowed or striated, but a large part of them are not; while in the "till" the stone not striated is the rare exception.

Above this bowlder-clay we find sometimes beds of loose gravel, sand, and stones, mixed with the remains of man and other animals. These have all the appearance of being later in their deposition, and of having been worked over by the action of water and ice.

This, then, is, briefly stated, the condition of the Drift.

It is plain that it was the result of violent action of some kind.

And this action must have taken place upon an unparalleled and continental scale. One writer describes it as,

"A remarkable and stupendous period--a period so startling that it might justly be accepted with hesitation, were not the conception unavoidable before a series of facts as extraordinary as itself."[2]

Remember, then, in the discussions which follow, that if the theories advanced are gigantic, the facts they seek to explain are not less so. We are not dealing with little things. The phenomena are continental, world-wide, globe-embracing.

[1. Dana's "Text-Book," p. 221.

2. Gratacap, "Ice Age," "Popular Science Monthly," January, 1878.]